This guest post written by Laura Shamas originally appeared at Venus in Orange. It is cross-posted with permission.

I’m not a horror film fan per se, but I’ve seen some scary, eerie stuff through the years, and Halloween is always a good time to view them. Are spine-chilling films always in demand because they help us dialogue with and about death? C.G. Jung once wrote: “Death is the hardest thing from the outside and as long as we are outside of it. But once inside you taste of such a completeness and peace and fulfillment that you don’t want to return.”

In the past year, I’ve been focused on seeing films directed by women because I participated in the “52 Films by Women” initiative. The 10 films detailed below (for adults, not kids!) have strong psychological components, too. I’ve divided them into well-known Halloween-ish folklore categories: monsters, strange illness, haunted house (ghosts), killer, losing one’s head (lost), witches, and vampires.

MONSTER

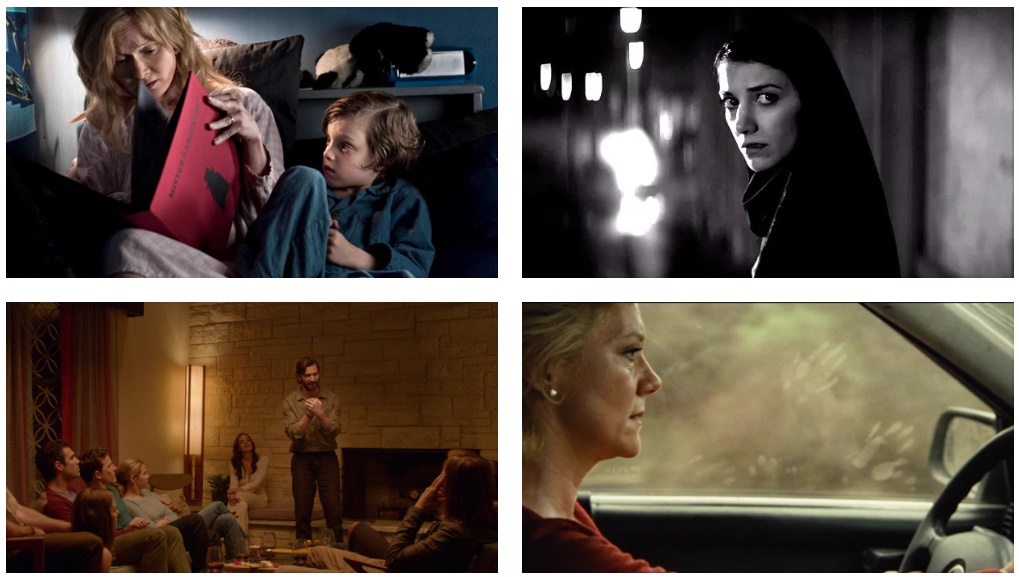

1. The Babadook (2014)

Written and directed by Jennifer Kent

This film is about a lonely widow, her young son, and their journey through grief. A mysterious book suddenly appears in their home, and launches a trajectory of events related to a home-invading monster. What a fascinating portrayal of aspects of motherhood in this film. The tone and cinematography are original; the key performances are strong. The conclusion is truly inventive, and, for me, unexpected. I can’t wait to see Kent’s next film. (Note: female protagonist. Available through streaming services, like Amazon and Netflix).

STRANGE ILLNESS

2. The Fits (2015)

Written and directed by Anna Rose Holmer

This film took my breath away. It centers on the extraordinary performance of Royalty Hightower as Toni, an eleven-year-old tomboy who hangs out with her older brother in the gym. When an all-girl dance troupe rehearses in the same community center, Toni becomes fascinated by the aspiring performers, and joins them. Then a strange sort of “illness” descends on the girls. As I watched the film, Arthur Miller’s play The Crucible came to mind; I’ve examined the film version of it before. I don’t want to give anything away, but the ending of The Fits was revelatory and mesmerizing. It involves a different sort of fear of the unknown and a transformation, but with tremendous female resonance. I eagerly await more of Holmer’s work as well. (Female protagonist, available on streaming platforms.)

HAUNTED HOUSE (GHOSTS)

3. A Cry from Within (2014)

Written by Deborah Twiss, co-directed by Twiss and Zach Miller

This is a ghost story with a particular feminine twist. Twiss stars as a married mother with two young kids. The film examines what happens when a city family moves into a drafty old mansion in a small town. This is a familiar set-up, and some tropes from the “haunted house” genre are used here predictably. Yet, as the film gradually turns towards its true theme, it held my interest: a spirited quest to heal a gruesome family history. Perhaps some of it is melodramatic, but I appreciated the different sort of twist in the third act; it concludes with a strong depiction of the “shadow” side of motherhood and ensuing generational repercussions. (Female protagonist, available on streaming platforms.)

4. The Invitation (2015)

Directed by Karyn Kusama

The film is about Will (Logan Marshall-Green), a grief-stricken man haunted by a past tragedy that occurred in his former house in the Hollywood Hills. As it begins, Will and his girlfriend hit a coyote in the rain on the way to a dinner party, hosted by his ex-wife and her new husband — a foreshadowing of what’s to come. At first it seems as if it’s going to be like The Big Chill: a gathering of old friends reminiscing, catching up, talking about what’s new. But then Will’s ex-wife and her new husband show a movie clip before dinner that sets the eerie tone of what’s to come. Let’s just say that if you’re invited to a dinner party in the Hills, this film will make you reconsider showing up. The house becomes a character of sorts, and old memories emerge like ghosts in flashbacks as terror reigns. (Male protagonist, available on streaming platforms.)

5. The Silent House (2011)

Co-directed by Chris Kentis and Laura Lau, written by Lau

This 2011 film, an American version of a 2010 Uruguayan film titled La Casa Muda, is another “Haunted House” type of film with a twist at the end. Based on a “true story” from its Uruguayan origins, the movie is seemingly filmed in a single continuous shot, which gives it a lot of tension. The Silent House follows Elizabeth Olson as Sarah, a young woman who, along with her father and uncle, are moving out of a dark old family home near a shore, and encounter strange noises, specters, old photos that no one should see, and more. Of course, the power is not on. When Sarah’s father is knocked out on a staircase, Sarah knows there’s someone else in the house. The revenge component in the film’s conclusion will resonate with many. (Female protagonist, available to stream on Amazon.)

KILLER

6. The Hitch-Hiker (1953)

Directed by Ida Lupino, written by Lupino, Robert L. Joseph, and Collier Young

As part of this initiative, I’ve tried to catch up on many of Lupino’s films. The Hitch-Hiker is considered the first mainstream film noir feature to be directed by a woman. It varies from standard film noir fare because of its desert locales (as opposed to urban settings). A tale of two American men who are ambushed by a terrifying killer in Mexico, and their attempts to escape danger, the film’s original tagline was: “When was the last time you invited death into your car?” (Male protagonists. You can watch it for free on YouTube here. A version with higher resolution also streams on Amazon.)

LOSING ONE’S HEAD (or LOST)

7. The Headless Woman (La mujer sin cabeza) (2008)

Written and directed by Lucrecia Martel

Made in Argentina, it’s perfectly titled. The film’s ominous psychological atmosphere produces a slow burn sort of scare and a dawning realization as you watch it; it’s not a conventional horror “scream” viewing experience. A strange auto accident on a deserted country road is at the center of a mystery; the protagonist is the driver Veronica or “Vero” to her friends (Maria Onetto), a middle-aged married dentist. We wonder: who or what has been hit? Is the victim okay? As the movie continues, we come to understand the true identity of the Headless Woman. (Female protagonist, available on streaming platforms, including Hulu.)

WITCHES

8. The Countess (2009)

Written and directed by Julie Delpy

Starring Julie Delpy, the film is a bloody biographical account of Hungarian Countess Erzsébet Báthory, who lived from 1560 to 1614. The film depicts the Countess’ fascination with death; even as a young girl, Báthory declared: “…I would have to raise an army to conquer death.” Thematically, this period piece examines the possibility that unrequited love could lead to madness, and that an obsession with youthful appearance could launch serial killings, as the Countess searches for virginal blood as a magical skin elixir. Because of the focus on bloodletting and torture in her story, Báthory became connected to vampirism through legend. But witches figure prominently in the film in several ways: Erzsébet’s estate is successfully run by a witch named Anna Darvulia (played by Anamaria Marinca), who’s also one of the Countess’ lovers; the Countess is cursed by a witch in a key roadside scene that changes her life: “Soon you will look like me”; and later, when she is on trial, Báthory is notably not tried for witchcraft, although she might have been. The ending brings information that forces a reconsideration of all we’ve just seen. (Female protagonist, available to stream on Amazon).

VAMPIRES

9. Near Dark (1987)

Directed by Kathryn Bigelow, co-written by Bigelow and Eric Red

I’ve long wanted to catch up on Bigelow’s earlier films, and have watched two so far as part of this initiative. But no Halloween film list is complete without a vampire movie, let alone a vampire Western like this one.

A lesson you learn quickly in Near Dark: never pick up hitchhikers at night in Kansas, Oklahoma or Texas. The movie is campy, bloody and violent; it debuted in October 1987, a part of the 1980’s vampire movie trend. The story revolves around Caleb (Adrian Pasdar), a young cowboy in a small mid-western town who inadvertently becomes part of a car-stealing gang of southern vampires. The frequent tasting of death in the film, and its repeated reverence for nighttime, reminded me again of Jung’s quote about death: “But once inside you taste of such a completeness and peace and fulfillment that you don’t want to return.” The ending of this one also pleasantly surprised me. (Male protagonist, available on DVD.)

10. A Girl Walks Home Alone At Night (2014)

Written and directed by Ana Lily Amirpour

This is a highly stylized, fascinating film. It’s a unique Persian-language film that follows a mysterious vampire figure named The Girl (Sheila Vand) who haunts the rough streets of “Bad City” at night in a chador, and encounters a young gardener named Arash (Arash Mirandi). Arash’s father is a heroin addict and his mother is dead; Arash is under threat from a tough character who keys his car as the film starts, and after that initial sequence, Arash befriends a beautiful stray cat who becomes part of the action. Amirpour’s film is so atmospheric, beautifully shot in black and white. The plot is untraditional; the ending was also unexpected. Some of the images are unforgettable, and the acting is strong. (Male and female lead characters, available via streaming.)

These ten “scary” films richly explore a range of psychological and social issues: grief; the arrival of puberty; abuse and repressed memories; the aging brain; unrequited love and growing old; justice; and becoming an adult. Most have plot surprises at the end, which makes the viewing all the more worthwhile.

See also at Bitch Flicks:

Why The Babadook Is the Feminist Horror Film of the Year

The Babadook: Jennifer Kent on Her Savage Domestic Fairy Tale

Patterns in Poor Parenting: The Babadook and Mommy

“The More You Deny Me, the Stronger I’ll Get”: The Babadook, Mothers, and Mental Illness

The Babadook and the Horrors of Motherhood

The Fits: A Coming-of-Age Story about Belonging and Identity

Male Mask, Female Voice: The Noir of Ida Lupino

9 Pretty Great Lesbian Vampire Movies

Kathyrn Bigelow’s Near Dark: Busting Stereotypes and Drawing Blood

A Girl Walks Home Alone at Night and Scares Us

Feminist Fangs: The Activist Symbolism of Violent Vampire Women

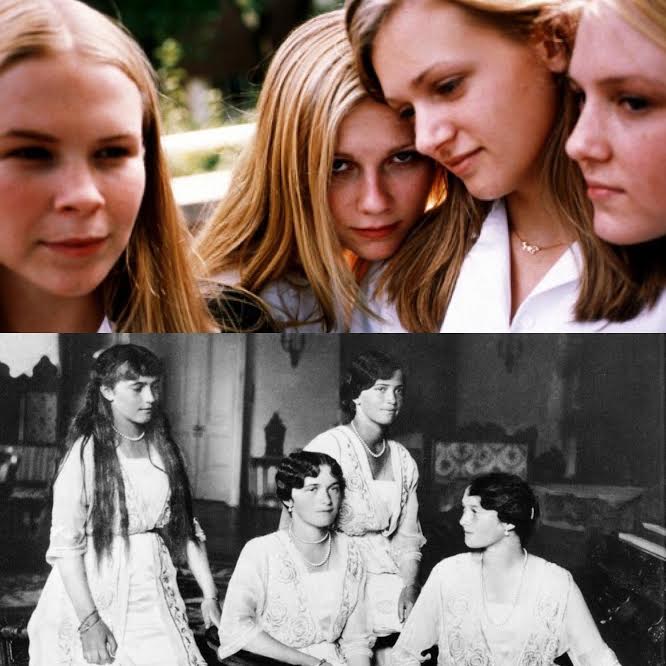

Laura Shamas is a writer, myth lover, and a film consultant. For more of her writing on the topic of female trios: We Three: The Mythology of Shakespeare’s Weird Sisters. Her website is LauraShamas.com.