|

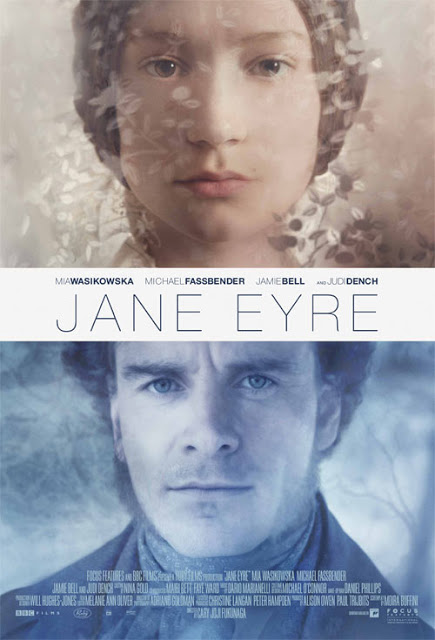

| Movie poster for Jane Eyre (2011) |

The ghosts of Jane Austen and Charlotte Brontë have suffered several film adaptations of their most famous works, and the problem with multiple film adaptations of the same novel, however well-meaning or loyal to the text, is that watching three versions of the same story before reading the book can numb one out to the brilliance of the original. I’ve seen this scene before, I’ve heard this dialogue before, I’ve had enough of this famous line because I got to see the three versions of Pride and Prejudice before I hit fifteen. Thankfully, Jane Eyre falls way below Pride and Prejudice in the best 100 books list, so its adaptations didn’t have as much reach or appeal of the latter. I did get to read articles and see films on the Brontës though and they were terribly interesting and creative people, their suffering contributing to the achey longing that filled their books. Lowood School with its pitiful conditions, for one, took its characteristics from the school where the writer lost two of her elder sisters.

The film uses a nonlinear timeline, choosing to begin with Jane’s long trek through the moors after she runs away from Thornfield Hall, her past played out as she is questioned by St. John, making her trudge down the unhappy path of memories again. This actually makes the film more interesting and we need that, because the story of a governess falling in love with her (much older) employer is one overdone in romance novels.

Mia Wasikowska awed us as Alice by blooming from an anxious young girl running away from an undesired proposal into a sword-wielding Jabberwock-killer. As Jane Eyre, she manages to convey the character of the (on the surface) insipid and sexless governess quite well. Blanche Ingram‘s blatant disrespect for her only reinforces the image of the dry governess, but the audience already knows that the deeply passionate Jane is more than that. As for Rochester, Brontë describes him as such:

I traced the general points of middle height, and considerable breadth of chest. He had a dark face, with stern features, and a heavy brow; his eyes and gathered eyebrows looked ireful and thwarted just now; he was past youth, but had not reached middle age; perhaps he might be thirty-five.

In the beginning, Adèle tells Jane the story of the vampire-woman haunting Thornfield hall, with Adèle’s doll pressed up against the window of a dollhouse in the background.

|

| Jane Eyre (2011) screenshot |

Rochester assumes Jane is a bit of a weirdo after seeing her fanciful paintings, telling her as much. Her response, implying that she’s even weirder than he thinks, arouses his curiosity. Her gaze is direct, she is not cowed by him, she possibly hates his (initially) overbearing nature because she’s had her fill of men like him. In their second conversation he reaches out to her almost desperately, bringing his hidden vulnerabilities to light. He finds a kindred spirit in Jane and the inexperienced Jane is moved. We can tell because when she first arrives at Thornfield hall, she curiously glances at a nude painting and after her second conversation with Rochester, she dares examine it more closely. Jane is a decent artist; but for the prudery of the times, she would be practicing human anatomy, but she can’t of course. And considering the reactions to the presence of the painting in the film even in this day and age, one can have plenty of reasons to imagine why*. There’s is more to this painting: Jane’s latent sexuality is aroused, and the presence of the painting is a way of showing a fleshly desire for Rochester. I know this is obvious, but being an artist myself I tend to disagree about equating the two.

The kissing scene in the movie plays itself out exactly as I imagined in the book. Immersed as I was in the tale my reaction was in keeping with the times: what a little strumpet. She’s so enamored by the kiss that she barely notices Mrs. Fairfax’s horror, beaming happily from ear to ear before running off to her room. The insipid governess blooms; she is not so sexless after all. Suddenly she’s a biological creature, and it’s almost vulgar for the audience.

This is just a weak moment for Jane. She is stronger than Rochester. Rochester makes two wrong choices and pays dearly for them. He’s taken in by a profitable, loveless marriage. He falls for a woman’s charms before he is betrayed but he adopts her daughter; both choices stretch his misery yet Rochester is a man with a conscience. Jane has no money or physical charms to speak of, and he finds that simplicity “becoming.” He thinks she won’t cause him any problems. He doesn’t however, speak a word in the defense of Jane after Blanche’s acidic remarks about her profession. Is he spineless and afraid to mess up his courtship with Blanche, or is he trying to make Jane jealous? Would it be patronizing and tiresomely chivalrous of him to speak out on Jane’s behalf? Would Jane be insulted if he shushed Blanche and came to her rescue? We don’t get to see that resolved; all we have to settle for is his rejection of Blanche.

After Bertha’s presence is revealed, Jane refuses to go through with the illicit marriage. There is more for Jane to fear than loneliness with this decision. In Lowood school, there was one thing that kept her passions in check: physical chastisement. Later when Rochester begs her to stay, she is faced with her physical vulnerability again when he says “I could bend you with my finger and my thumb! A mere reed you feel in my hands.” Jane keeps her individualism intact at yet another level in spite of the memory and trauma of past physical violence. If she had said yes she would have to live with the specter of the first wife lurking in the background for the rest of Bertha’s life. As an unloved child, she is not lured into the comforts of heart and hearth, compromising the laws of societal convention that Rochester, who obviously has been burned by both love and marriage, is willing to put aside. Though Rochester’s revulsion for all manmade laws is understandable and his story worthy of pity, she does not hitch her fate to his, and for the abandoned child not to lunge at such an offer is surprising, for why should Jane worry about societal convention? In the book, it’s because it’s ethically wrong. In the movie it is because she must respect herself (thank you Cary, Moira). In spite of being confronted with the fear of loneliness once again, accentuated by her cold and the endless trek through the moors, Jane manages to make a decision well-balanced by intellect and intuition. She does it once again, refusing the offer of marriage from St. John, not giving in in spite of him berating her “lawless passion,” and in spite of owing him her life, because it would go against her nature and thus “kill” her. Jane is a classic proto-feminist**; she controls her passions enough to work out her priorities, but not at the expense of her deepest desires.

When Jane returns after the fire, she finds what remains of the painting is but the frame, the canvas burnt out and the half-burnt doll sitting inside it (symbolism much?). Jane has been jolted out of her brief experience with earthly pleasure (burnt nude painting), and her love for Rochester has matured. Bertha (the doll) is gone; no hurdles remain between Rochester and Jane’s union. Jane picks up the doll with some sadness when Mrs. Fairfax finds her. In spite of Bertha being Rochester’s ball and chain, neither of them blames her. Considering the lack of knowledge in the field of mental health, Rochester was being kind for the time by locking her up. She was still the madwoman in the attic though, standing like a rock between Jane’s and Rochester’s happiness, and once she was gone, they could all breathe a sigh of relief and move on. Perhaps she represents the wild, passionate part of Jane’s psyche that is now released, but I’m not going to stretch that one out…

The central story of the complex lone woman, unloved and unwanted–matched with the world-weary hero set in a background that’s far from sumptuous–is in great danger of turning into a great depressing drag of a tale, so it’s incredibly important for that spark and pull between them to work. The script by Moira Buffini aids this, taking only the relevant bits from the novel and chipping away at them so that they shine at the significant parts of the movie, avoiding the verbal diarrhea that can come with being loyal to a classic novel. The music too, soars lonesome and yearning to match the tormented souls of the main characters. The lighting is superbly planned, muted and misty in the day and full of deep flickering shadows in the night, the house dark and creaky just like the gothic Thornfield of the book. From what I saw of the deleted scenes (those are always interesting) Helen’s ghost arrives to guide Jane through the moors. This coupled with Jane’s hearing Rochester’s voices would have been clairvoyant overkill, so I’m glad that was edited out. Jamie Bell is amazing as St. John, a warmer version than the book. Judi Dench plays Mrs. Fairfax, sticking to the role of a secondary character and not pressing her presence, the trait of a self-assured and experienced actress***. The claim to the horror element by the crew though, I can’t really place. This movie wasn’t remotely nail-biting or scary.

Whether Jane Eyre purists agree with me or not, there’s little not to like about Jane Eyre (2011), and I eagerly anticipate the release of director Cary Fukunaga‘s next film.

*It’s art, barely pornographic, get over it people.

**Not sure if the term applies, but I love it so I’m using it!

***For who can forget the woman who called James Bond “a sexist, misogynist dinosaur“??

———-

Rhea Daniel got to see a lot of movies as a kid because her family members were obsessive movie-watchers. She frequently finds herself in a bind between her love for art and her feminist conscience. Meanwhile she is trying to be a better writer and artist and you can find her at http://rheadaniel.blogspot.com/.