Guest post written by Mychael Blinde.

NSFW | Trigger warning for survivors of sexual assault

Warning: Spoilers abound!!

Splice explores gendered body horror at the locus of the womb, reveling in the horror of procreation. It touches on themes of bestiality, incest, and rape. It’s also a movie about being a mom.

Though it received somewhat

lackluster reviews, I encourage anyone interested in feminism and film to give Vincenzo Natali’s sci-fi body horror film a try.

Splice features female characters who are intelligent, emotionally complex, and incontrol. They’re not perfect, but they are three dimensional characters whose decisions drive the story. (One of them morphs into a male, but we’ll get to that.)

Splice asks a lot of questions about the terms and conditions of conception, gestation, birth,and motherhood, all without stabbing the viewer in the eye with reductive answers.

It also features some campy moments. Hipster scientists shout things like “It was the only way!” Academy Award winning actor Adrien Brody expresses his frustration by throwing down not just his jacket, but his scarf as well!

If you can stomach the juxtaposition of big thinky concepts and stilted clichéd dialogue, you will find Splice a thoroughly enjoyable mindfuck of a film.

Elsa Kast (Sarah Polley) and Clive Nicoli (Brody), long-term partners in romance and biochemistry, have developed a method to splice the DNA from various animals together to create hybrid creatures.

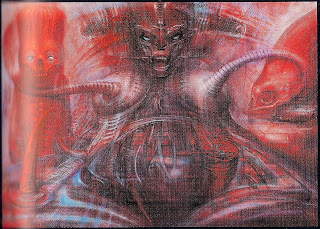

Viewers are actually birthed into the film from the perspective of Fred, the couple’s latest scientific endeavor, a male companion to their first hybrid, Ginger.

|

| Splice |

Elsa and Clive aspire to splice human DNA to develop cures for genetic diseases, but the pharmaceutical company funding their research puts a halt on all splicing until the duo can synthesize the medicinal protein necessary to create a commercially viable lifestock drug.

Newstead Pharma’s financial interests are represented by Joan Chorot (Simona Maicanescu), who insists Elsa and Clive begin “Phase Two: The product stage.”

|

| Joan Chorot (Simona Maicanescu) in Splice |

Joan doesn’t get a lot of screen time, but her brief appearances are a pleasure to watch. She’s articulate and always in control. It’s awesome to see a woman kicking ass in the role of the money-grubbing corporation, and Joan is a stellar example of how to do it right.

After their splicing research is shut down, Clive suggests they quit, but Elsa convinces Clive to proceed with the human splicing and to generate an embryo.

|

| Clive Nicoli (Adrien Brody) and Elsa Kast (Sarah Polley) in Splice |

In both the romantic and the professional relationship between Clive and Elsa (and this is a movie very much interested in the conflation of work and sex), Elsa is in charge.

Over and over, Elsa insists that they take the next step. She is the opposite of what I call

the Male Protagonist’s Girlfriend — a pretty lady bystander who supplements the male protagonist’s story arc.

Elsa and Clive also deviate from the typical representation of long-term monogamous heterosexual partners: it is he, not she, who desires to have a child:

Elsa: “You are talking about having a kid.”

Clive: “Is that so unreasonable?”

Elsa: “Yeah, because I’m the one who has to have it…”

Clive: “Come on. What’s the worst that can happen?”

Elsa: “How about after we crack male pregnancy?”

Meaningfully, this discussion is cut short by an alert sent from the machine housing the hybrid fetus. When they arrive at the lab, the embryo is all grown up and preparing to evacuate the biochemically engineered womb.

Though Elsa doesn’t gestate and birth the baby from her own body, the birth experience is physically traumatizing for her. She becomes trapped in the birth canal and is injected with poisonous serum. In a rare moment of control, Clive saves Elsa. But after the birth, Elsa again takes charge: she refuses to allow Clive to kill the female hybrid and insists that they raise her in the lab.

Weirdly, the couple begins to function less like scientists and more like normal parents: frustrated because the baby won’t eat, stressed out because it won’t stop crying. However, unlike most parents, their baby has a stinging whip tail, and they are forced to relegate their progeny to the laboratory’s basement to keep her existence a secret.

|

| Elsa (Sarah Polley) in Splice |

Elsa becomes more and more emotionally attached to the creature, and eventually names her Dren. Clive is worried about their secret being revealed and disturbed by Elsa’s displays of maternal affection. Nevertheless, he resigns himself to raising her, and Dren grows to be a young adult in a matter of months.

One night, Clive and Elsa realize they haven’t boned down lately. Clive doesn’t have any condoms, but Elsa says, “What’s the worst that could happen?” – suggesting that she’s decided she wouldn’t mind gestating a child, maybe? – and they have at. This is the first of three sex scenes in Splice.

Cinematically, their lovemaking is depicted as underwhelming. Neither Elsa nor Clive take off any clothing. Creepily, Dren watches.

Meanwhile, pressure is building at the pharmaceutical company.

Their presentation at the shareholders’ meeting goes disastrously wrong. Unbeknownst to Clive and Elsa, their specimen Ginger has changed into a male, and Ginger and Fred tear each other apart and splash guts and blood all over the audience. Not good PR.

In deep shit with the company, Clive and Elsa are forced to relocate Dren to Elsa’s deceased mother’s farm.

Here we learn the backstory of Elsa’s childhood; themes of feminism, motherhood, and family history come into play.

We learn that Elsa’s mother forbade Barbies and makeup. Elsa explains that “She said makeup debased women.” The word “feminist” is never used in Splice, but Elsa’s mother’s Barbie-banning and makeup-denying seem emblematic of a certain type of feminist parenting.

We also learn that Elsa’s mother raised her in substandard living conditions, relegating her to a ramshackle, barely furnished bedroom.

Initially I viewed this as a problematic conflation of being a feminist with being a neglectful person and bad mother. But it’s far more complicated than that.

Elsa expresses her love for Dren by giving her the very things her mother denied her.

|

| Dren (Delphine Chanéac) and Elsa (Sarah Polley) in Splice |

But the Barbie and the makeover don’t make Dren happy; in fact, the Barbie explicitly makes Dren sad. Looking into a mirror, she holds the doll’s long blonde tresses against her bald head and becomes upset.

Over the course of the film, Elsa locks Dren up in a lab, then a basement, and eventually her mother’s barn, and Dren resents her for it. Elsa seems unable to break the cycle of her own mother’s physical and emotional neglect.

Perhaps the idea is that makeup is not a substitute for ideal living quarters and engaged parenting. What matters isn’t whether or not you give your daughter a Barbie, but whether or not you lock her in a barn.

And it turns out, Dren really is Elsa’s genetic daughter. To his chagrin, Clive discovers Elsa used her own DNA to create Dren: “Why the fuck did you want to make her in the first place? Huh? For the betterment of mankind? You never wanted a normal child because you were afraid of losing control. But an experiment…”

He doesn’t finish the sentence, but it seems clear that Elsa is using science as a way to disassociate herself from motherhood while still being able to create and raise a child. Presumably we’re to understand that Elsa’s desire for complete control stems from her tragic upbringing: “Look at your family history,” Clive exhorts.

Elsa tries to convey her genetic connection to Dren by explaining to her: “You’re a part of me, and I’m a part of you. I’m inside you.” She strives to smooth over their mother-daughter animosity, but the two wind up in a physical altercation that results in Elsa knocking Dren unconscious, tying her up, stripping her naked, and removing her tail and stinger. This scene has undertones of both castration and rape. Elsa has become a monstrous mother scientist.

Clive is horrified by Elsa’s actions, but she informs him that she is going to use Dren’s amputated stinger to finally synthesize the protein and heads to the lab, where she succeeds.

|

| Elsa (Sarah Polley) in Splice |

She tells off her obnoxious supervisor: “When some real scientists get here, come take a look.”

While Elsa’s away, Dren seduces Clive. If Elsa’s sin is her obsessive need to control, Clive’s sin is his inclination to relinquish control.

This is the film’s second sex scene. Cinematically it is sensual, queer in a fantasy-mythical-creature sort of way, strange but beautiful. Ominously, Dren grows back her tail stinger. Then Clive notices Elsa has come back and is watching them. She storms out and he chases her. Back at their apartment, Clive and Elsa decide that they finally have to kill Dren.

But when they return to the barn, it turns out Dren is already dying. After she dies, Clive’s brother (who also works in the lab) and their supervisor show up. He announces he knows their secret and demands to see the human-spliced creature. Elsa informs him that Dren is dead, throws a shovel at him and says, “See for yourself.”

Except Dren is no longer buried behind the barn. Like Ginger, she has morphed into a male, and in the film’s climax, he kills everybody but Elsa.

|

| Dren as male in Splice |

A note on the gender transition: I am uncomfortable with the representation of Dren’s metamorphosis from female to male. It is predicated on the idea that transitioning from a female body to a male body is horrific, and it exploits trans individuals by sensationalizing the transitioning body as evil and freakish. It’s not trans positive. I understand that Splice’s story necessitates this metamorphosis and that Dren isn’t exactly a human, but let’s call out problematic shit when we see it.

Chasing women through the woods at night is a staple of slasher flicks, but this movie isn’t about slashing – it’s about splicing. Dren chases Elsa through the woods, but instead of slaughtering Elsa, Dren rapes her.

This is Splice’s third sex scene. Cinematically it is gut-wrenchingly horrifying, as any rape depicted onscreen needs to be in order to convey the awfulness that is sexual violation. Dren’s rape of Elsa is as disgusting and awful as Dren’s sex with Clive is beautiful and sensual.

When Elsa screams “What do you want?” Dren replies: “Inside…of…you.”

Clive stabs Dren with a branch (wielding the metaphorical phallus) as Dren orgasms, but Dren is not killed, and attacks Clive. Elsa pulls her pants back on and bashes Dren in the head with a big rock. This critically injurs Dren, who takes a moment to survey the situation – then stabs Clive with his tail. Elsa bashes Dren in the head again, killing Dren once and for all.

Elsa is the character who cut off Dren’s stinger and the one who deals Dren the death blow. And yet in his final moments, Dren chooses to kill Clive. Why?

Because inside of Elsa is a womb, the growing space for a new creature. And sure enough, in the film’s resolution we discover that Elsa is pregnant. Of the three sexual encounters that take place in this movie, the reproductively viable encounter is the rape. Elsa lives to be the final girl not because she wields a chainsaw, but because she wields womb. (And a big rock.)

I appreciate both The Fly and Prometheus because each asks its audience to empathize with a woman who desperately needs an abortion. I also appreciate Splice for asking its viewers to honor Elsa’s decision not to abort. Joan makes it clear that Elsa has a choice: “Nobody would blame you if you didn’t do this. You could just put an end to it and walk away.” (Would that this were the standard response to women experiencing unwanted pregnancies!)

But Elsa does not to put an end to it. Why does she decide to bring it to term?

Sure, the company’s giving her a shitload of money for gestating Dren’s offspring. But throughout the film, Elsa has insisted on moving forward with human splicing experiments. Perhaps she sees this as a necessary extension of that research.

Or maybe this is another chance for Elsa to use science to mediate motherhood. Is the pregnancy Elsa’s punishment, or her redemption? We’ll never know. All she says is, “What’s the worst that could happen?”

The film closes with a shot of the two women, the film’s only surviving characters, looking out a window.

Mychael Blinde is not a scientist, but she is afraid to give birth. She is interested in representations of gender in popular culture and blogs at Vagina Dentwata.