|

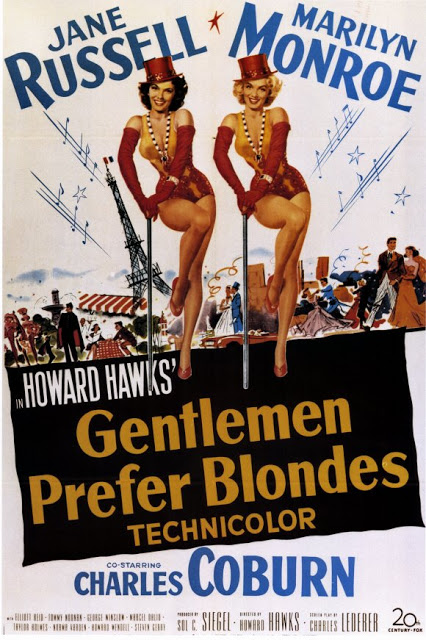

| Gentlemen Prefer Blondes Movie Poster |

Marilyn Monroe has to be one of the most misunderstood household names. When people think of her, sure, they think of her beauty and sex appeal, but they also think of her drug addiction, her early death, rumoured plastic surgery, rumoured promiscuity, her stage name, and her difficulties as a performer. No one ever seems to know about her good points. They seem to think that her dumb blonde sexpot persona is her actual personality, when, in fact, she was acting. She was actually an intellectual who loved reading (and I’m talking difficult texts like Proust and Nietzsche) – her favourite photographs of herself are of her reading. There’s a reason she married Arthur Miller! She was also an early civil rights advocate – Ella Fitzgerald would recollect that Monroe personally called the owner of popular club Mocambo, which at the time was segregated, and demanded that Fitzgerald be booked as a performer immediately, promising that she’d be at a front table every night, and bring the press with her, if the owner did so. Her actions made sure that Fitzgerald would never have to play a small club again. Marilyn Monroe could act (in both comedic and dramatic roles), dance, and sing, and yet all that she is remembered for is her looks and her personal demons. She deserves better, especially as someone I consider to be an early feminist icon.

|

| Marilyn Monroe & Jane Russell in the film’s opening sequence |

The friendship between Lorelei Lee and Dorothy Shaw is one of the most positive female friendships depicted on film, and is one aspect of the adaptation distinctly improved from the original novella by Anita Loos. (Yes, I’ve read the source material this time.) In the original novella, Lorelei is a flapper who keeps a diary of her daily events and describes both her ambitions of wealth and her attempts to juggle three suitors at once. She is vain, poorly educated (the prose is littered with deliberate misspellings), and disdainful of other women. Dorothy is supposedly her friend, but she often makes sarcastic snipes at Lorelei’s expense (which Lorelei is too dimwitted to pick up on). They’re a lot closer to frenemies in the original, which is a surprisingly misogynistic depiction of women from a female writer. The musical version instead makes Lorelei and Dorothy inseperable. They are absolutely devoted to each other and protective of one another. They disagree on relationships – Lorelei believes in only dating rich men and falling in love with them later, whereas Dorothy is a romantic who keeps falling in love with poor men. Each thinks the other is foolish when it comes to relationships, but they accept each other’s differences and are loyal to each other before any other man in their lives. Sisters before Misters.

|

| Marilyn Monroe & Jane Russell |

The film also depicts the women as unmistakably intelligent, albeit in different ways. Dorothy is very obviously meant to be the “smart” one, who corrects Lorelei’s mistakes, catches on to other people’s insinuations, and is always ready with a witty retort. But while Lorelei might be “book dumb,” she’s not stupid. Together, Lorelei and Dorothy are master manipulators, and she’s far more devious than she lets on. Famously, at the end of the film, she convinces Gus’ father to let them marry through some admittedly clever logic. (“Don’t you know that a man being rich is like a girl being pretty? You wouldn’t marry a girl just because she’s pretty, but my goodness, doesn’t it help?”) Dorothy isn’t entirely smart either, because she tends to think with her heart over her head. She knows that Ernie Malone is a private detective out to ruin her best friend’s life, but falls in love with him anyway. Notably, however, she makes it clear that she chooses loyalty to Lorelei first.

|

|||

| Marilyn Monroe in the “Diamonds Are A Girl’s Best Friend” sequence |

Yes, the film is flawed, especially if taken at its apparently anti-feminist face value. But contextually, I feel that this film’s depiction of women is quite fair for its day. Yes, it would be nice if the girls weren’t stereotypes and Lorelei wasn’t a blatant golddigger, but then, where would the plot be? Not only are its stars, Marilyn Monroe and Jane Russell, important landmarks in feminist history, but their characters are too. Their friendship is absolutely ironclad – they put each other first, even though both are looking for love in different ways. Their confidence in their intelligence, lifestyle, and sexuality is incredibly liberated for what was supposedly a time of suffocatingly patriarchal morality. And lastly, the famous song “Diamonds Are A Girl’s Best Friend” might be about celebrating materialism, but is really about a woman’s dreams of financial indepdencence. All things considered, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes is surprisingly feminist.

Myrna Waldron is a feminist writer/blogger with a particular emphasis on all things nerdy. She lives in Toronto and has studied English and Film at York University. Myrna has a particular interest in the animation medium, having written extensively on American, Canadian and Japanese animation. She also has a passion for Sci-Fi & Fantasy literature, pop culture literature such as cartoons/comics, and the gaming subculture. She maintains a personal collection of blog posts, rants, essays and musings at The Soapboxing Geek, and tweets with reckless pottymouthed abandon at @SoapboxingGeek.