Watch more cool animation and creative cartoons at Aniboom

Directed by Michael Varnum.

The radical notion that women like good movies

Watch more cool animation and creative cartoons at Aniboom

Directed by Michael Varnum.

The film treats Dee with respect. We learn that her four children have three different fathers, but her private life is mostly kept private. When the DA questions Dee about “how many men she’s had sex with by the age of 24,” her lawyers quickly step in to remind them–and us–that a woman’s character is not to be judged by her sexual history. This was a refreshing moment in the film, when even in so-called women’s films, slut-shaming is regular and almost perfunctory. In another moment of the film, we see testimony from the DA’s ex-wife and daughter, and it’s the daughter’s mocking of her own father’s (racist) slut-shaming that ultimately brings him down. (An ironic and uncomfortable twist is that while Dee’s private life is off limits, the DA’s private life is the strongest testimony against him.)

American Violet is the kind of movie I don’t like to criticize, because it’s a movie interested in Doing Good. It’s a sincere film, it addresses real-life social problems, it has a heroine we root for and get to see achieve a victory, despite the odds. And, it’s enjoyable to watch. Doing Good movies rarely achieve blockbuster status; they typically don’t have large budgets, stars, or major marketing campaigns. Doing Good movies are the kinds of movies we wish the public, at large, would see. However, films that expose social ills tend to suffer from cliched characters, predictable narratives, and overly simplified stories. American Violet–despite its powerful performances—doesn’t escape these problems.

Everyone seems to agree that crack cocaine use is higher among Caucasians than any other group: most authorities estimate that more than 66% of those who use crack cocaine are white. Yet in 2006, 82% of those convicted and sentenced under federal crack cocaine laws were African American. When you add in Hispanics, the percentage climbs to above 96%. Since enactment of this law, the 100 to 1 ratio has had a devastating and disproportionate impact on the African American and Hispanic communities.

Ultimately, I liked this film, and encourage others to see it. I do feel ambivalence about it, and am a little disappointed in some of the choices made, but do think it’s a strong, woman-centered film.

We previewed Seraphine in June of last year, when it was opening in select cities. Now you can rent it on DVD.

amazon.com synopsis:

Séraphine is an elegantly fictionalized biopic about 19th century modern primitive painter, Séraphine de Senlis, who was a contemporary of Henri Rousseau’s. The tale spans approximately 25 years during which Séraphine and her champion, German art critic and collector, Wilhelm Uhde, survive two wars and drastic economic changes that affect the art market. Martin Provost’s feature is completely character driven, and as such relies on Yolande Moreau’s caring portrayal of the eccentric Séraphine, and Ulrich Tukur’s calm, academic demeanor as Mr. Uhde. In Provost’s telling of this virtually unknown story, Séraphine is a middle-aged woman working as a housekeeper in Senlis, France, when Uhde arrives as a guest and discovers that this odd woman is a talented visionary artist. Since Uhde’s main focus is garnering respect and precious Parisian salon space for artists deemed “naive,” it is an uncanny and fortuitous coincidence that he stumbles upon Séraphine.

Sarah Boslaugh writes,

In one of those strokes of luck upon which lives can turn, the art dealer Wilhelm Uhde (Ulrich Rukur) sees one of her paintings at a neighbor’s house. An early champion of Picasso and the primitive painter Henri Rousseau, Uhde recognizes her raw talent and becomes her patron. Besides his professional interest in her art, he may be motivated by the fact that they are both isolated outsiders, she by her poverty and mental illness, he by his German nationality and homosexuality (the latter is underplayed in the film).

In his review, “The Vision of an Uncanny Painter,” A.O. Scott writes:

… the director is properly immersed in the sensual and spiritual dimensions of Séraphine’s art, which grows out of an ecstatic — both in the erotic and religious sense — engagement with the natural world. She paints fruits and flowers in arrangements that at first look merely decorative, like the patterns on wallpaper or pottery, but that on closer examination are charged with a marvelous and unsettling power.

Kenneth Turan of the L.A. Times writes:

A long time is spent with Seraphine and her daily routines in the town of Senlis before we have any notion of her as an artist. Stolid and seemingly simple, Seraphine is treated like a piece of furniture by the people she works for, but in her private moments we sense a yearning in her spirit, an unspoken, almost pagan passion for nature in all its manifestations.

When we do see her paintings of flowers and trees, we come to understand that making art is a holy act for Seraphine.

She paints because of a kind of spiritual compulsion, as if she were a devout member of a religion with but a single worshiper. Art is not a choice or an option, but a brutal necessity.

In her review, Liz Braun writes,

Seraphine is a film about the painter Seraphine Louis, a scrubwoman from the French village of Senlis whose paintings hang in museums around the world.

For the subversive among you, the movie is also a commentary on the class divisions and other pesky social inequities that abound in the art world.

You can also listen to a review/discussion of the film on NPR.

Stephanie’s response:

The reason I refuse to take Sex and the City’s self-proclaimed celebration of sisterhood very seriously is because the women rarely permit one another to slack off on their duty to maintain Fabulous Fashionista status at all times. As I stated earlier, Miranda gets shit for not porn-waxing and Samantha gets shit for gaining weight (from comfort-eating due to her tanking relationship—because that’s another thing we all do, ladies!). They permit Carrie’s days of depression when Big leaves her at the altar, literally feeding her at one point, but I still couldn’t help but cringe at that simultaneous depiction of female-infantilizing coupled with creepy mommy-moment.

Yet I believe they do really love one another. You’re right to point out the refreshing portrayal of women who aren’t in direct competition or who aren’t conniving against one another. One could also point out many scenes where genuine love exists among them—my favorite scene is when Carrie sucks it up and takes the train (but not without fur coat!) to Miranda’s apartment so she won’t be alone on New Year’s. It feels … honest, in a way that so much of the rest of the film doesn’t.

I never saw the television series. From what I’ve heard and read, the women were very much unashamed sexual beings. So I had to ask myself after I saw the movie, “Where the hell is all this sex I’ve been hearing about?” Samantha has sex exactly zero times on-screen. Miranda struggles with sex and her husband’s infidelity—it’s very much implied that he cheats because she won’t sleep with him (another one of her wife-duties shirked). Charlotte claims to have a wonderful sex life, but … where’s the evidence? Perhaps the film wants to show the progression of their lives and the complications that might come with aging, but they chose to do it by regressing to traditional gender expectations regarding marriage and pregnancies and preoccupations with couple-hood.

I get the feeling that the show, while still portraying the women as rich and fashion-obsessed, actually represented their shunning of traditional, more conservative ideas regarding adult womanhood. They didn’t have to get married and have babies and buy houses. They could have sex! And live in the city! And have fulfilling careers! If that’s the case, the film-version seriously dropped the ball.

With scenes like Miranda telling her child to “follow the white person with the baby” when they’re looking for a new apartment in a less-rich neighborhood; with scenes like Carrie showing up to reclaim her metaphorical glass slipper while her metaphorical prince conveniently awaits in her giant, specially built metaphorical (closet)-castle—the film only reinforces good ol’ traditional American values about class, heterosexual relationships, and especially about womanhood.

In his NYT review of Toe to Toe, A.O. Scott says

If “Toe to Toe” were a young-adult novel, it would be embraced and argued about in classrooms and eagerly read by thoughtful teenage girls. The film’s observations about race, class and friendship are clear and accessible without being overly didactic, and its sometimes harsh candor about female sexuality would not be unfamiliar to devotees of contemporary adolescent literature. But because it is a movie — the first nondocumentary feature film by the writer and director Emily Abt — “Toe to Toe” is likely to languish in art-house limbo, far from the eyes of its ideal audience.

Tosha (Sonequa Martin) is a poor African American girl in a private prep school who is pushed by her grandmother (Leslie Uggams) to believe in herself and her ability to get into Princeton. She also encourages her to play lacrosse because no African American girls do. It is on that field that she meets Jesse (Louisa Krause) a troubled, sexually provocative white girl who has been kicked out of many schools. Jesse and Tosha are drawn to each other and become friends even while the outside world is conspiring against them. But like most teenage girls they also compete. Their friendship is messy, and at times disappointing and destructive. But they try, which is more than can be said for Jesse’s busy single working mom (Ally Walker) who is so oblivious to her daughter’s needs and desperation that you want to throttle her.

*This is a guest post from Jesseca Cornelson.

*This is a guest post from Jesseca Cornelson.

I had high hopes when I saw that the screenplay was adapted by Nick Hornby. His story “Nipple Jesus” ranks among my favorite ever, and I was impressed with his book How to Be Good, which is written from the first-person point of view of a doctor mother who strays from marriage to her househusband. In each of these—the story, the novel, and the film—I find his presentation of the moral ambivalences to be the most striking element. Each, it turns out, is concerned with how people negotiate the appearance of morality with actual morality, and each implicates pretty damningly middle-class values of maintaining an appearance of morality while being oh so quick to compromise any actual morals the moment it becomes convenient or self-serving. It makes me wonder how much of Hornby himself we hear in David and Danny when first one tells Jenny not to be bourgeois in her moralizing and then the other turns her moral condescension around on her by noting that she had watched them steal from little old ladies without saying much either. I guess I should admit that I’m using “morality” and “moralizing” to stand in not only for everyone’s obsession with Jenny’s virginity and the various duplicities perpetrated in the film, but also for that middle-class form of snootiness that is so quick to judge others in its desire to be respectable.

An Education is at its best when it subtly complicates and plays against audience expectations. The scenes where Alfred Molina’s jolly but domineering Jack practically stutters and falls over himself as he is charmed by David are delicious. We, wise audience, see how easily the big man’s desires for upward mobility are used to seduce him as well. Dominic Cooper’s Danny, David’s art thief buddy, is worried enough that Jenny will get hurt that he says something to David about it, but then doesn’t actually do anything about it except dance flirtingly with Jenny.

What bugs me is how tidily Hornby’s script draws on familiar types for characterization and sets up a whole series of foils. Take Olivia Williams’ portrayal of Miss Stubbs, Jenny’s English teacher. The movie tells us in a conversation that Miss Stubbs is both smart and pretty (unlike some films which present pretty actresses as ordinary—Kate Winslet is a Plain Jane in Little Children, puh-lease!). And yet the film presents Miss Stubbs as dowdy, as if smart women are incapable of doing anything other than wearing severe buns (or, for one all-too-brief scene, a ponytail that manages to be both severe and sloppy) or compulsively quaffed with prim bobs, like the headmistress’, something like an upper-class, executive severity. Yawn. And how convenient that after Jack’s rant about Oxford trees, school trees, private tuition trees, and pocket money trees growing out in the garden, David justifies his art theft by saying that “these weekends [in Oxford and Paris], and the restaurants and the concerts don’t”—here it comes!—“grow on trees.” Convenient, too, the discussion in Jenny’s English class on Mr. Rochester’s blindness in Jane Eyre and King Lear, with its own themes of blindness. When it comes to David, Jenny and her family are so hungry for the world he offers that they are willingly blind to his deceits. Jenny watches gleefully as he forges the signature of C.S. Lewis, whose acquaintance he falsely claims in order to get Jenny’s parents’ permission to take her to Oxford for a week, and Jack later tells Jenny that he and her mother Marjorie (Cara Seymour) had heard on the radio that Lewis had long since moved to Cambridge and rather than accept David’s lie they convinced themselves that the radio announcer had it all wrong.

The script isn’t bad. After all, if movies didn’t routinely take shortcuts by using familiar, stylized codes for characterization, they couldn’t tell their intricate tales in about 100 minutes. It’s just that the script is so tidy and effective that it doesn’t come anywhere close to transcending its form. At times I wondered if the film would have felt as artful if it had been cast with more familiar Hollywood types, say Julia Roberts as Miss Stubbs or Anne Hathaway as Jenny, both of whom I find exude a sweetness that always makes me aware of how terribly charming they are. Would the film have been as engaging if everyone had American accents? I wonder if audiences’ own aspirations to sophistication might make us a bit blind to how ordinary this film is.

And here’s where I want to shift gears and put An Education in conversation, however briefly, with another film from this year that blew me away, Lee Daniel’s Precious, which also features a young woman, who’s been manipulated by an older man and whose hopes for the future are likewise pinned to her education. I know Precious has been accused of being exploitative, and maybe it is, but it is a far more interesting film, in terms of characterization alone. Here we have another female teacher who reaches out to her young student. And while Paula Patton’s Ms. Rain is also smart and pretty, she’s a fully developed character and not just a type. She in fact is presented as pretty and well groomed (a pretty, neatly dressed, well-groomed lady English teacher, oh my!) and, in another surprise, she’s a lesbian! Ms. Rain’s relationship with Precious, far from being limited to a few words of encouragement or knowing warnings, is central to the film. In An Education, all of the relationships seem comparatively superficial. Jack’s semi-mock anger at having to pay for so many lessons and longing for social standing is nothing compared to Mo’Niquie’s brilliant turn as Precious’ self-loathing and enraged mother, who is herself starved for affection.

And back to that ending. Holy voice over! It’s never a good sign that all of a sudden you need a voice over to close a movie after a minute-long montage of redemptive studying. How tidy, how comforting: see Oxford was the way to go after all! I would have preferred if the film had ended with the long closing shot of Jenny hugging her knees on the stairs, her face caught somewhere between relief and worry, not fully capable of enjoying her victory. Yeah, I know: The Graduate. But we all get off easy when the movie lands very near where it would have had Jenny never met David. Oh, sure she’s now been to Paris and all the boys she dates at Oxford are, we’re told, really boys. But her earlier questions about the value of an education and the limited options for women go unanswered. She was right to tell Emma Thompson as the headmistress that “it’s not enough to educate us anymore. You’ve got to tell us why you’re doing it.” It is indeed “an argument worth rehearsing”—an argument that the film fails to rehearse even as it resolves with Jenny’s acceptance to Oxford. What is the value of an education if the only things you can do with it are teach or go into civil service? Compare that to Precious, whose closing moments of victory aren’t tinged with yet another level of superior condescension, but rather present a young woman, HIV-positive before the AIDS cocktail, walking into the sunlight hand-in-hand with the children fathered by her own father. It’s a much more genuine ending. What do I mean by that? I suppose that the victory is both more humble and more hardly earned. As Precious walks down the street, we know her life cannot help but hold more difficulty and heartbreak. As Jenny cycles carefree down a different street, we suspect that the Oxford education will serve her just fine. So maybe what I mean by genuine is that Precious offers up the rare ending that opens out, leaving the audience with a sense that the character’s life and struggles will continue in spite of her current moment in the sun.

And isn’t that more like real life anyway? I know boatloads of smart, pretty women who find disappointment in their careers and relationships as much as those of a plainer sort, but we don’t really get the sense that Jenny will struggle with the difficulties of being a smart woman in 1960s Britain that she had so clearly articulated earlier in the film. And that seems a bit counterfeit.

Jesseca Cornelson is currently working on a collection of documentary poems about the history of Mobile, Alabama, which will serve as her dissertation for a doctorate in English and Comparative Literature from the University of Cincinnati. She blogs about her research and writing at Difficult History.

*This is a guest post from Kate Staiger.

*This is a guest post from Kate Staiger.

The film begins by examining an employee’s reaction as he is fired by Ryan Bingham. Bingham guides a tragic moment into a hopeful possibility with a speech he uses on many of his subjects. He is good at his job, but no matter how good he is, it doesn’t take away from the desperation of unemployment. The movie’s plot could begin and end with this theme; an exploration of what it’s like to have the job as corporate assassin, but it doesn’t. The experience of firing and being fired takes the backdrop, while other plot lines emerge and take the movie through a series of love-twists and moral-turns.

Early on in the movie, Bingham is joined on the road by his new, pesky associate, Natalie (Anna Kendrick). Natalie possesses all the qualities of a young, overly-confident college grad. Her character is not a part of Kirn’s novel, though appears in the movie as a sort of moral compass for Bingham (the novel offers disease as Bingham’s wake-up call). Natalie challenges all of his life-decisions with her know-it-all youthfulness. Their contrast of philosophy, hers being more traditional, his being non-committal, is occasionally interesting. But most of the time, she just comes off as a stompy-teenagery type that adds drama instead of story.

Bingham’s other female sidekick is Alex (Vera Farmiga), a sexy, strong-corporate-woman. She meets Bingham, a fellow super-traveler, in a hotel bar. They hit it off, do the deed, and she becomes the love interest. They exchange contacts and meet for booty calls in cities where they happen to cross paths while on business. As their relationship progresses, he goes through the formal “sworn-bachelor-stumbles-into-love” process, schlepping it all with sentimentality and making it confusing to understand the direction of this movie. Aren’t I supposed to be watching a movie about the tragedies of people losing their jobs? Or am I supposed to be focused on Ryan Bingham’s thawing heart? Or no, it’s this: Ryan Bingham has a hard job and travels a lot. It makes his life experience void of human connections. He is now in the process of making it better as a result of his pesky sidekick on one shoulder, and his hot woman-equivalent on the other. YES!

This movie is fun to watch. The typical Clooney exploits are there; dashing smiles, good hair and clothes, favorable lighting, and witty bantering all carry him through the movie. Oh! And the very funny Jason Bateman plays the ruthless boss. AND the movie passes 2/3 of the Bechdel Test; it’s just that the women leads’ conversations with one another happen to be about their ideal man. Damn. The idea for the movie is appealing, the dialogue, at times, is smart and funny. The movie runs its course through predictability and wraps up with an ironic ending (which is actually good), but “Best Picture” at the Oscars? I’d be surprised…or wouldn’t I?

Kate Staiger lives in Cincinnati. Her current interests include: free-internet programs, fixing her toilet all by herself, and the band A Hawk and A Hacksaw.

*This is a guest post from Sarah Domet.

District 9: A Film I Want to Like

District 9, directed by Neill Blomkamp, depicts a futuristic Johannesburg, South Africa, nearly two decades after a massive alien spacecraft grinds to a halt in the sky, hovering silently just above the cityscape. The malnourished, bipedal, crustacean-like aliens, given the derogatory nickname “prawns,” now live in a militarized refugee camp, aptly named District 9 and policed by the South African government. However, crime, weapon trade, and even interspecies prostitution have overrun this filthy alien shantytown, and soon Multi-National United (MNU), a private company, is contracted to relocate the prawns to a more easily patrolled area, one much farther from the city limits. Enter Wikus van der Merwe (Sharlto Copley), a middle-management Yes-Man put in charge by MNU head (coincidentally, also his father-in-law) to lead the evacuation and relocation of these creatures. (His primary job is, hilariously, to go door-to-door, politely asking the prawns to sign an eviction notice while MNU mercenaries with machine guns look on. How bureaucratic!)

However, after a karmatic run-in with some dark, oozy liquid from an alien weapon he confiscates, Wikus contracts a particularly nasty virus, the main symptoms which turn humans into prawns. The film follows Wikus on his pursuit to find a cure for his disease, which entails working closely with Christopher Johnson (Jason Cope), an intelligent and sensitive prawn, to relocate the confiscated liquid; evade the MNU folks, including his evil-doer father-in-law, who are trying to kill him for his unique DNA; and heal his broken relationship with his wife, who believes, according to the lies of her father, that Wikus has slept with an alien. Cue Bill Clinton: “I did not have sexual relations with that woman!”

Science fiction is often a useful allegorical genre that allows filmmakers to discuss socially and politically charged issues in a way that is palatable to average moviegoer. Take Minority Report, for example, or The Matrix, or the film-adaptation of Orwell’s novel 1984. District 9 attempts to borrow from this rich tradition, and it’s nearly impossible to critique this film without pointing to the overt, sometimes too obvious, racial commentary that serves as the backbone of the plot. District 9 is, after all, set in South Africa, the geographical epicenter of Apartheid. However, to the BitchFlicker who turns to this movie looking for deep political or social commentary, I say this: Don’t waste too much time looking. While the film seems to want to reveal a reverse racism, one where the historical victims (South Africans) become the villains, propagating against the prawns the same violent and discriminatory acts that were once committed upon their own people, in the end the movie either: a.) substitutes gunfire, gore, or special effects at any moment the movie veers too far from the surface, b.) relegates Big Ideas to Small Peanuts by reducing the plight of the prawns to the pursuit of Wikus’s happiness, or c.) reinforces the very racist notions that it wishes to resist (see representation of Nigerian gangsters.)

If you’ve seen the Lord of the Rings trilogy, you’re aware that Peter Jackson is the master of the Buddy Film genre. It should come as no surprise, then, that Jackson, the producer of District 9, brings us yet another masculine-charged cinematic world, full of gore, gun fights, chase scenes, buddy bonding (even if interspecies), and special effects, but a world also nearly void of female characters.

District 9 operates with what I’d call an absent feminism, which isn’t quite an anti-feminism but a disregard for a female world altogether—except when a minor feminine presence functions as off-stage impetus for the lead character. Aside from a few bit parts, the most prominent female role is that of Wikus’s wife, Tania (Vanessa Haywood), who, although rarely seen onscreen, becomes the driving motivation for Wikus to risk his life to find the cure for his “prawnness,” befriending, out of necessity, Christopher Johnson, the same alien he tried to evict earlier in the day. (Wikus didn’t know then that Johnson actually built his shack atop the Mothership’s missing module; he’s been diligently working for twenty years to fix it, and was nearly finished when pesky Wikus confiscated that black fluid.)

Wikus’s wife, who is given no real identity, save the fact that she is torn between the age-old allegiance to her father and loyalty to her husband (implying that she most certainly “belongs” to one or the other), won’t relinquish hope of her husband’s return by the film’s conclusion. Someone is leaving strange gifts on her doorstep, gifts oddly similar to the ones dear hubby Wikus used to give her. Blomkamp insinuates that she’s a steadfast wife who will do her wifely duty and wait faithfully for her disappeared husband. The viewer is given no back-story or insights into their relationship; yet, forced upon us is the heavy-handed notion that they really do love each other—like, in that super-deep, eternal-love kind of way. Their story, of course, is a bottom-tiered thread in the narrative.

The final scene contains the most sentimental gesture of the film; Blomkamp depicts a now full-prawn Wikus sculpting a rose from a heap of scrap metal. Ah—a delicate rose amidst the muck and hopelessness of an alien nation. Perhaps most disturbing is the emotional weight Blomkamp wants this scene to carry: Poor Wikus! Now he’s the other race, er, I mean species! Will that Christopher Johnson ever return with the magical cure for Prawness, as he promised?

Poor Wikus? What about the entire prawn nation, displaced noncitizens forced to live in the squalor of regulated militarized zones? What about the fate of millions of other prawns with more troubling stories (such as genocide, for one) than a nebbishy Yes-Man turned courageous No-Man turned Prawn? But, like, he’ll really, really miss his wife! And, like, they can’t be together if he’s a prawn, now can they? But Look! He makes her flowers out of trash! How sweet!

Perhaps Blomkamp’s vision is to convey the notion that our greatest hope for an internationally practiced humanism is to fully experience the isolation and desperation at the individual level. I want to believe that this is his message. But I fear I may be giving him too much credit, for in the end Blomkamp never fully considers the implications of violent discrimination and segregation on anyone but (white, male) Wikus, the original perpetrator of this alien apartheid in the first place. In the end, Wikus becomes a victim, too, yes. However his victimhood is meant to be understood as a courageous act of martyrdom, and, more specifically, one of choice. After all, Wikus told Christopher Johnson to board the Mothership without him; Wikus would stay behind to fight the bad guys. If nothing else, Wikus was given the luxury of choice and self-determination, a luxury not afforded to the “others” of this film, woman and prawn alike.

I want to like District 9—I really do. And I will admit to enjoying the film on a simple story level. There’s plenty to admire, including the visual grittiness, the quickness of the pace, moments of dark humor, and the cool special effects, if you’re into that kind of thing. The script is original, too, and examines the “Man vs. Alien” genre in a new and interesting light, asking the pointed question: What the heck would we do with millions of immigrant aliens if they ever came to Earth?

However, I couldn’t help but think there was a certain dishonesty about the movie, too. Instead of using science fiction to serve the purpose of political allegory, District 9 uses political allegory as a Trojan horse—supplanting an action-packed buddy movie in the place of a film that initially promises the viewer something much more substantive.

While I don’t think this film will win the Oscar for Best Picture, I certainly don’t think it’s the worst film ever nominated. If nothing else, District 9 does generate discussion about some often taboo topics, even if the film itself doesn’t provide any satisfying answers.

Sarah Domet received her Ph.D. in English Literature and Creative Writing (Fiction) from the University of Cincinnati in 2009. She spends most her time writing, teaching, cooking, gardening, taking long drives in the country, and doing other things that would lead you to believe she’s 80 years old. Look for her book, The 90-Day Novel (F+W Publications, 2010), due out this fall.

If Pixar shit into a bucket, it would still be box office gold. Fifteen years ago Pixar catapulted itself into a movie-making monopoly with Toy Story. Since then they’ve continued to rehash the same predictable (and often adorable) story lines about the secret lives of bugs, monsters, cars, rats, and superheroes. They are the main reason movie theatre parking lots continue to fill up with dented minivans and half-crushed McDonald’s milkshake containers. But still, no matter how annoyingly formulaic their stories are, I am a sucker for them. Confession: I was in line to see Up before many ten-year-olds in my neighborhood and am not ashamed to say that I cut right in the middle of a group of 15 kids to make sure I got better seats than they did. I have also been known to hush children during Pixar films. I’m that guy.

Up came in the aftermath of Wall-E (last year’s Oscar winner for Best Animated film), though Up takes a decidedly safer route. At Pixar, like most movie houses, there are A and B movies. The A movies at Pixar are written and directed by Andrew Stanton (Wall-E, Finding Nemo, Toy Story) and Brad Bird (Ratatouille, The Incredibles). Up is a B movie (only produced by Stanton and Bird), and pulls out many Pixar tricks to throw something together in time for a summer release date (Pixar Trick #1: Summer release date).

Up tells the story of widower, Carl Fredricksen (voiced by Ed Asner). The movie begins with Carl as child, donning explorer goggles, and ogling over a film about his explorer idol, Charles Muntz (voiced by Christopher Plummer). Muntz, the captain of The Spirit of Adventure (PT #2: Name everything with vague, idyllic names), claims he’s found a new beast in a far-off part of South America. When scientists debunk Muntz’s discovery as a fabrication, Muntz floats off back into the wild to prove the scientific community wrong. Carl, still a boy, travels home from the theatre and is stopped by Ellie, a young, rambunctious child with, let’s face it, WAY cooler explorer garb than Carl. She inducts him into her own explorer club and within a 5-minute musical montage they are married, live their life together, save money for a future trip they never take, and lose a child. (PT #3: Emotional montage where characters gaze at each other instead of speak.) Ultimately Ellie dies, leaving Carl alone and curmudgeonly.

Insert Pixar dilemma: Pixar has a girl problem. I don’t want to dwell too much on this, as the blogosphere has already run Pixar through the dirt (as it should). Noted in Linda Holmes’ blog on NPR, after 15 years of movie making, Pixar has yet to create a story with a female lead. Ellie is the only female voice in this entire movie and she is dead and gone within the first ten minutes. She’s not even allowed an actual voice as an adult. (see PT: #3). The entire story is told by a male octogenarian and a boy, Russell (voiced by Jordan Nagai), who is seventy years Carl’s junior, and who—instead of being a real-world boy scout—is a Wilderness Explorer (see PT: #2). It is devastating to watch this movie in a theatre of mothers and young girls who are forced to stretch their own experiences into the identities of these stock male characters. (PT #4: Employ an inordinate amount of male writers.)

There is a mother bird character that is quirky and loves chocolate, flitters around on the screen as the comic relief, and who, as the film progresses, becomes the desire of Muntz in order to prove to the scientific community that he’s not crazy. But even this bird’s identity is wrapped up in her overly compelling (sarcasm) storyline to return to her bird babies. When she is returned, the world apparently rights itself on its axis and all sense of justice is restored. (PT #5 – Everything in Pixarland turns out alright in the end.) But enough is enough. Fifteen years with no female leads is an embarrassment. I’m sure all the male writers at Pixar (see PT #4) might have noticed what a shame it was had they not been so busy shooting their wads into each others’ over-inflated male-dominated story lines.

Enough about wad-shooting; here’s a quick summary. When Carl faces eviction from encroaching developers, instead of being taken to Shady Oaks retirement home, he fills his house with thousands of balloons and (much like Australia’s Danny Deckchair) takes to the sky. (PT #6 – Shiny, colorful screenshots make the best advertisements.) While in the air, Carl realizes that Russell is with him. The goal is to get the house to Paradise Falls (see PT #2), so that Carl can fulfill a life-long promise he had with his dead (mute) wife, Ellie. They land on the wrong side of the falls and spend much of the movie carrying the house (PT #7: Every character has some burden they have to overcome.) to the opposite side of the rocky crag. They encounter talking dogs (PT #8: Every animal can talk.) that use them to catch the mother-beast-bird thing. Chaos ensues, dreams are crushed, lives are rebuilt (see PT #7), and Muntz falls off the dirigible to his death. (PT #9: Kill off the bad guy.)

Up is a kid’s movie, but because we live in a world where movie writing/directing are 99.9999999% dominated by men, Up is set in a man’s world. It’s a boy’s story, for boys, about boys, where mute girls die off early. But for all the times I cringed at Up’s blatant disregard for women, I will say that I practically drooled on myself because the movie was so damned visually stunning. (see PT #6). When those balloons come out of Carl’s chimney and his house begins to lift off the ground, I think it doesn’t matter who is in the movie theatre, everyone’s mouth is open and everyone is ready for the ride. Pixar has a pulse on what makes a good movie, and they are artistically capable of pulling it off, but they rely on storylines that readily neglect female roles. (PT#10: No female leads.) As far as I’m concerned, they can toss that trick in the trash.

Travis Eisenbise works at a non-profit environmental organization in New York City. His fiction and non-fiction have appeared in (super small) journals, so it’s okay that you’ve never heard of him. He lives in Brooklyn with his partner who likes to make bread in a bread robot.

imdb synopsis, as composed by Anonymous:

The Blind Side depicts the story of Michael Oher, a homeless African-American youngster from a broken home, taken in by the Touhys, a well-to-do white family who help him fulfill his potential. At the same time, Oher’s presence in the Touhys’ lives leads them to some insightful self-discoveries of their own.Living in his new environment, the teen faces a completely different set of challenges to overcome. As a football player and student, Oher works hard and, with the help of his coaches and adopted family, becomes an All-American offensive left tackle.

The real synopsis, as composed by me:

The Blind Side depicts the story of a white woman who sees a Black man walking down the street in the rain. She tells her husband to stop the car, and he obliges—oh, his wife is just so crazy sometimes!—then, out of the goodness of her white heart, she allows him to spend the night in their offensively enormous home.Unfortunately, she can’t sleep very well—the Black man might steal some of their very important shit! But the next day, when she sees that he’s folded his blankets and sheets nicely on the couch, she realizes that, hey, maybe all Black men really aren’t thieving thugs.

Then she saves his life.

There’s a way to tell a true story, and there’s a way to completely botch the shit out of a true story. Shit-botching, in this instance, might include basing the entire film around an upper-class white woman’s struggle to essentially reform a young Black man by taking him in, buying him clothes, getting him a tutor, teaching him how to tackle, and threatening to kill a group of young Black men he used to hang out with.

However, a filmmaker might consider, when telling the true story of Michael Oher’s struggles to overcome his amazing obstacles, to actually base the film on the true story of Michael Oher’s struggles to overcome his amazing obstacles.

Instead, we get Leigh Anne Tuohy (Sandra Bullock) as the adorable southern heroine. We get the white football coach’s unwillingness to stand by his Black player, until one day, he has a revelation on the field and screams at a referee for making yet another terrible call against Oher. The result? The viewer gets to cheer—not for Oher, mind you—but for the lesson the coach finally learned: racism is bad! Yay white people! We rock! This is all very problematic because the story, which should’ve been about Oher, plays from beginning to end like a manipulative montage of white guilt.

Basically, each white person learns a valuable lesson in this movie: Black people aren’t bad, as long as they’re reformed by upper-class white people.

While we have Oher, a soft-spoken, likable football player, we also have Oher’s former friends, a group of young Black men based entirely on stereotypes of inner-city gun-toters. In those scenes, Black men are the polar opposite of Oher, consistently sexually harassing women, waving guns around, starting fights, and generally looking all dangerous and shit. So when Tuohy confronts them for messing with Oher, the viewer can’t help but root for her; she’s merely protecting her adopted son after all.

As a result, the audience strongly identifies with an upper-class conservative white woman as she threatens a group of inner-city Black men. She says, “If you so much as set foot downtown you will be sorry. I’m in a prayer group with the D.A., I’m a member of the NRA, and I’m always packing.”

We’re meant to find that funny. I don’t find it funny. Because overall, the moral of that scene, and of this entire fake true story about Michael Oher, basically goes like this: White woman good. Black men bad. White woman make one black man good.

She even stands up to her upper-class white friends who also, as luck would have it, are based on the worst stereotypes of upper-class white women you can possibly imagine: cold, snobbish, morally superior, complete assholes who occasionally get together for lunch and discuss money or something. The scenes with these women serve one purpose: for them to act overtly racist so that Leigh Anne Tuohy can go all heroine on our asses again, telling off the women and leaving them alone and flabbergasted at the table. How dare she!

If you count those non-conversations about nothing as “conversations among women,” then I suppose this film technically passes the Bechdel Test. But the portrayal of women in this film? Embarrassing.

At first, I wanted to identify with Bullock, to see her as a strong, complicated female lead. But when I realized her character is nothing more than a vehicle for upper-middle-class white America to feel good about itself, well, that pretty much killed it for me.

To make matters worse, if possible, the filmmakers use Tuohy’s outspoken personality to emasculate men, especially the football coach. She’s overly feminine, too, which makes her outspokenness almost adorable, and, in turn, permitted. Even her husband has given up trying to argue with her, which is played as a cutesy marriage thing, where the emasculated husband does whatever his wife says because she’s all blunt and endearing.

And as a mommy, my god! What does she think she’s doing bringing a looming Black man into her home? What kind of mother would do that? These are the questions asked by the stereotypes-disguised-as-upper-class-white-women, and they jar Tuohy enough that she goes immediately into Good Mother mode, having a sit-down with her daughter to discuss Oher’s presence in their home. Maybe that’s fine, but where’s Daddy in this discussion?

What I’m saying is this: I don’t know what the hell the Academy was thinking this year when it tossed up The Blind Side as a Best Picture contender, but remember, this is also the same group of people who awarded the Best Picture Oscar to Crash in 2005. Five years have passed—is it already time to recognize yet another racist film that blindly (ha) reinforces the exact stereotypes it attempts to rail against?

*This is a guest post from writer Lesley Jenike.

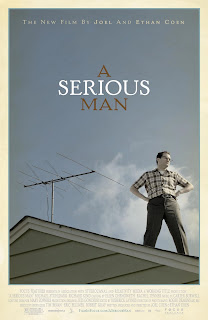

In the entire film, one woman appears–and she’s a wife and mother. She doesn’t have any conversations with other women about things other than men. The film is a Bechdel fail.

In the entire film, one woman appears–and she’s a wife and mother. She doesn’t have any conversations with other women about things other than men. The film is a Bechdel fail.

Okay, I’ve only seen one of the other nominees, but I’m pretty sure about this: Kathryn Bigelow’s The Hurt Locker is the film of the year. She is the director of the year.

Anyone reading this post is probably familiar with the movie, at the very least for the narrative of its director’s sex and, unfortunately, her relationship with another nominee in the same category. I want a woman to win the award for directing; in the history of the Academy Awards, only three women before Bigelow have ever been nominated (Lina Wertmüller for Seven Beauties, Jane Campion for The Piano, and Sofia Coppola for Lost in Translation). While I don’t want to lose focus on the how good the movie actually is by focusing exclusively on Bigelow’s sex, a few things need to be said.

War is a subject typically dominated by male voices. The Hurt Locker was written by a man. Its protagonists are men. But to make the mistake that war is a male subject is to make a classic sexist assumption. War is a universal subject. One need not be a man to create art about war, or to study texts of war (movies, books, paintings, etc.). In her Salon review, Stephanie Zacharek may put Bigelow’s accomplishment best:

She’s sympathetic toward her characters without coddling them or infantilizing them. Bigelow is an outsider looking in and she knows it, but that status also allows her some freedom. The guys in “The Hurt Locker” are human beings first and men second. The point, maybe, is that you don’t have to have a dick to understand what they’re going through.

We are all implicated in war. If women seem less likely to focus on war, our silence is implicated.

Do I want to see a female director lauded for a woman-centered film? Without question. But Kathryn Bigelow shouldn’t be blamed for making the kinds of movies she’s made for two decades. I didn’t see a woman-centered movie this year that was as powerful and well-made as this movie. And that is a problem.

In The Hurt Locker we have a close and careful character study of three men and their approaches to dealing with combat and their jobs on an elite IED diffusing team at the height of the war in Iraq. Sanborn (played by Anthony Mackie) is a rules man, relying on procedure to maintain his cool. William James (in an Oscar-nominated performance by Jeremy Renner) is the risk-taker, the cowboy figure we want to be the all-powerful hero, but who we quickly come to see is more than a little bit undone. Eldridge (Brian Geraghty) seems to be the youngest and least experienced member of the team; he’s terrified, skeptical, and, ultimately, the most likely to survive post-combat. At times the filmmaking is claustrophobic; we see the world as they see it–as they’ve been trained to see it. Every Iraqi is a potential enemy; even a child.

The Hurt Locker is a powerful anti-war film, which can almost get lost in the breathless action sequences. Its message is subtle but unmistakable: war utterly breaks you. The final scene of the film, which has been criticized for its ambiguity (we see James voluntarily back in action after a brief return home and a too-familiar scene representing shallow American excess), is actually a haunting, almost terrifying reminder of our implication in war. If you see James as a hero at the end of the movie, you haven’t understood a frame of the film you just watched. Yet the film teases us with a traditional genre representation of the hero. We want him to be a hero, only finding joy in the adrenaline rush of war, but he isn’t. He’s an empty shell of a person, nothing more than an animated suit heading toward…nothing. He’s walking off into the abyss. War has ripped out his humanity. This is what we do to our soldiers: we ask them to do the impossible in combat, and it destroys them.