This is a guest post from Megan Kearns.

Tag: 2000s movies

Best Picture Nominee Review Series: Juno

|

| Juno |

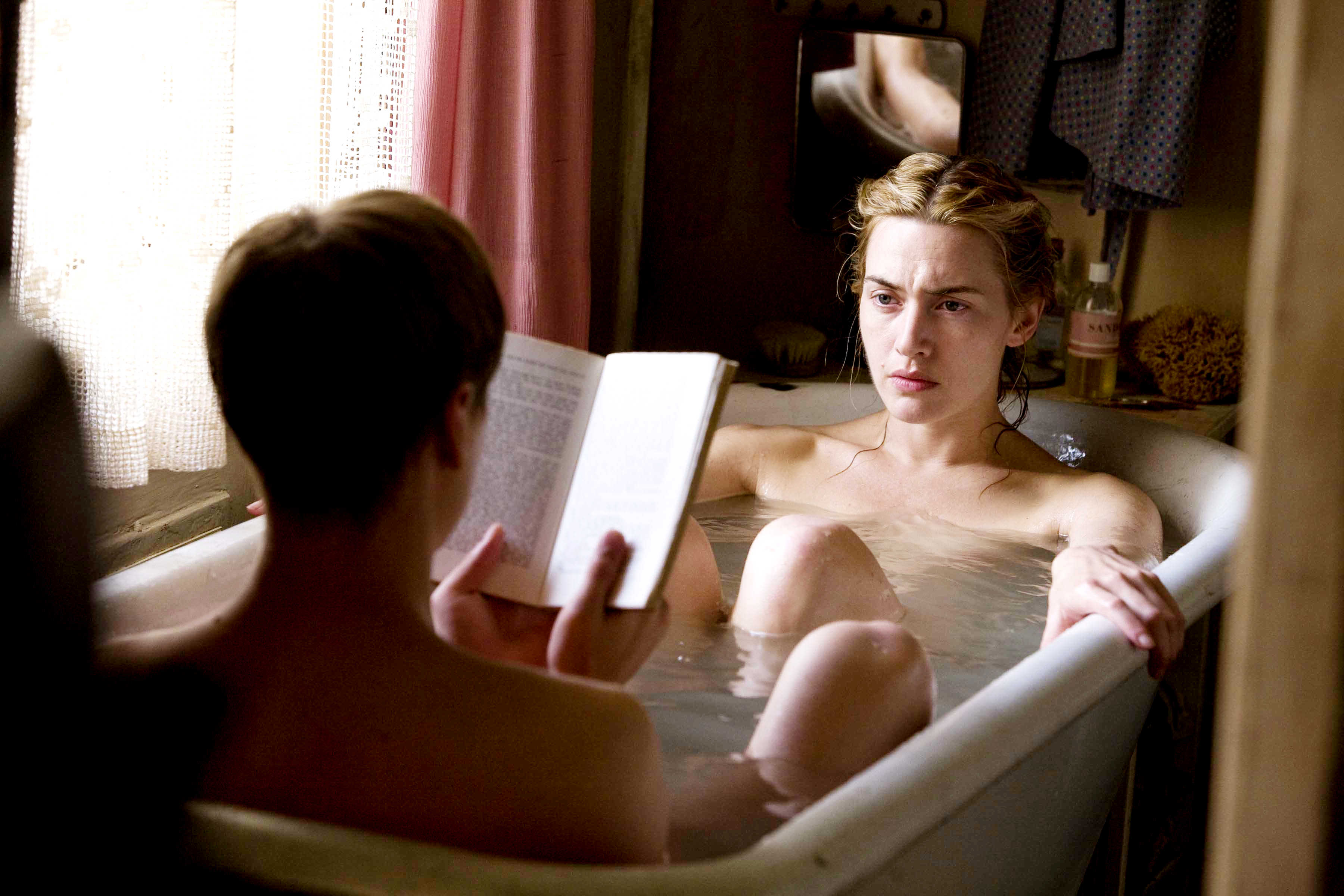

It turns out, however, that after an initial adjustment period to the dialogue (and a question about whether the film is set in the early ‘90s), Juno turns out to be planted in a feminist worldview, and is a film that teenagers, especially, ought to see. It was thoroughly enjoyable, funny and touching. I liked it so much that I watched it again, but when I started to write about it, what I liked about the movie became all the more confusing. I loved the music, although Juno MacGuff is way hipper than I was (or am), and I saw a representation that reminded me of myself at that age. I saw a paternal relationship that I never had and a familial openness that I’ve also never had. I saw characters who I wanted as my childhood friends and family.

It turns out, however, that after an initial adjustment period to the dialogue (and a question about whether the film is set in the early ‘90s), Juno turns out to be planted in a feminist worldview, and is a film that teenagers, especially, ought to see. It was thoroughly enjoyable, funny and touching. I liked it so much that I watched it again, but when I started to write about it, what I liked about the movie became all the more confusing. I loved the music, although Juno MacGuff is way hipper than I was (or am), and I saw a representation that reminded me of myself at that age. I saw a paternal relationship that I never had and a familial openness that I’ve also never had. I saw characters who I wanted as my childhood friends and family.  The film’s real progressive moment comes when Juno realizes that her idea of perfection isn’t perfect. She realizes that a father who doesn’t want to be there would be as bad as a mother who hadn’t wanted to be there. She sees that a father isn’t a necessity–or perhaps simply that two parents aren’t a necessity. Yet what does this all add up to mean? There’s certainly a moment of female solidarity (and this isn’t the only one, certainly, in the film), and a difficult decision that she makes independently. But, as with other conclusions I’ve made, I’m left with the question of “So what?”

The film’s real progressive moment comes when Juno realizes that her idea of perfection isn’t perfect. She realizes that a father who doesn’t want to be there would be as bad as a mother who hadn’t wanted to be there. She sees that a father isn’t a necessity–or perhaps simply that two parents aren’t a necessity. Yet what does this all add up to mean? There’s certainly a moment of female solidarity (and this isn’t the only one, certainly, in the film), and a difficult decision that she makes independently. But, as with other conclusions I’ve made, I’m left with the question of “So what?”Best Picture Nominee Review Series: Atonement

I’d like to start this review with a confession: Atonement is the second book in my long history of reading that has made me so angry, so upset, that I literally threw it across the room.

Both as an Academy Award-nominated (and winning, for soundtrack) film and as a book adaptation, Joe Wright’s Atonement succeeds. The film is a gorgeous and gritty, if frustrating, portrait of childhood, of war, of love, of lies and the lies one tells to correct them.

The first section of the film and novel set up the plot. The wealthy Tallis family has temporary custody of their lesser-off red-headed cousins, the Quinceys, and young Briony (Saoirse Ronan) is determined to lead them all in a play to celebrate her older brother Leon’s homecoming. Mother Tallis is sick in bed, and older sister Cecilia (Keira Knightley) is awkward around the son of the Tallis’s lawn worker, Robbie (James McAvoy) and excited to hear that her brother is coming home, despite news that he’s bringing along a friend, cocky Paul Marshall.

In direct contrast to this innocence comes Paul Marshall, introduced as a dapper gentleman who intends to make money off of the war with his Army Amo chocolate bar factory. He descends upon the safe haven of the nursery where Lola is meant to be watching over her twin brothers. “You have to bite it,” he says, handing her a bar of chocolate, his face stony.

The sexuality, too, of Robbie has another angle. His attempts at a polite apology devolve quickly into crude sexual expression. Robbie is faced with the sheer absurdity and irrationality of expressing sexual attraction to one who is of a higher class. Paul Marshall experiences the opposite problem, his power over Lola used to his advantage as he inflicts first rough treatment and then a rape in the woods. That power keeps Lola from seeing the truth, that she has been mistreated, brutally; Paul Marshall keeps Lola at his side, and she eventually marries him.

What follows is Rob and Briony’s means of atoning for their crimes. Rob, unable to fight the accusation against the wealthy and certain young Tallis, is sentenced to prison and then to fight in WWI. Briony, realizing years later that there were cracks in what she witnessed, that there are, perhaps, alternate truths, becomes a nurse in an attempt to undo some of the wrong she has inflicted upon Cecilia and Robbie.

A story is being crafted, an attempt to fill in the blanks. An attempt to create rational cause and effect as happens in all stories when we are young. An attempt to understand what must be truly random and unpredictable. Motive must be established.

But of course, things don’t follow a logical order. The wrong person is blamed for a tragedy while another gets off scot-free. War happens and the best and worst of us are lost, caught in causes we might not respect ourselves. Illness, a car crash, a lightning strike. Do we blame Briony, then, for trying to set order in her confusing world? Do we blame her for attempting to set things right that she helped to set wrong? I remember upon first completing the novel, my rage was so complete, so strong. I hated Briony for what she had done, for creating ugly and beautiful lies to cover up the truth, for believing that life was as simple as “Yes. I saw him with my own eyes.” I hated Briony for the very reasons that I love reading and watching films: writers and directors create lies for us, and we indulge in them. Fiction is called such for a reason–it isn’t real.

The soundtrack, interlaced with the sounds of a typewriter, never lets us completely forget that this is a story that is being crafted. It is no mistake that the first shot of the movie is Briony typing away at her play, “The Trials of Arabella,” taking her work very seriously. Briony expresses the difficulty of writing: that a play depends on other people.

The difference between play and story, as Briony postulates, are similar to the difference between novel and film. McEwan spends pages describing the intricacies of the vase, complete and then broken, whereas in a film, the vase is simply there. A long camera shot transports the viewer from room to room; instead of the turn of pages, the soundtrack interacts with the actions on screen instead of, for example, a rowdy neighbor or interrupting child pulling attention from the work.

While it is, in a way, refreshing to give the narrative over so completely to a woman in what is most certainly not a “chick flick,” and while Cecilia appears to be a strong, fierce woman in charge of her own sexuality, and while Briony, if not the most trustworthy of narrators, is more than skilled enough to do the job of telling this story, both of their stories center around Robbie. Even small conversations between Briony and Cecilia, Briony and Lola, Briony and a young nurse at training devolve quickly into a discussion of Leon, or Robbie, or marriage.

Any deconstruction of the traditional romantic narrative does have the potential to be feminist, however in this case, because the story is filtered not only through Briony Tallis’s obsession with that very narrative but through a male author and director, the deconstruction is seen as a loss of something good. A loss of cherished innocence, of childlike femininity.

There is no denying the technical mastery of Atonement. Simply look at the long shot as Robbie arrives at Dunkirk, despair and small hope surrounding him and swooning around him as the camera floats through soldiers waiting. Look at small consistent hints of cracks in the narrative, look at changes in perspective looped together by setting and soundtrack. Atonement is a master work of fiction and of film, but feminism is not something I believe it can claim.

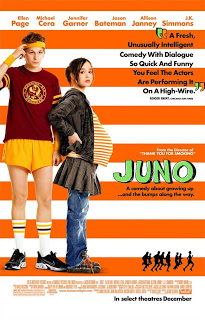

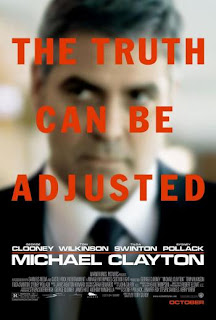

Best Picture Nominee Review Series: Michael Clayton

|

| Best Picture nominee Michael Clayton |

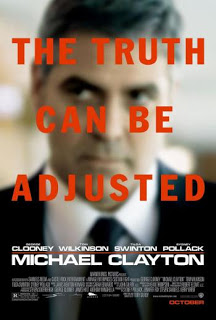

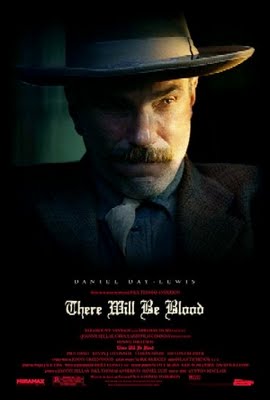

Best Picture Nominee Review Series: There Will Be Blood

|

| Best Picture Oscar nominee, There Will Be Blood |

I’m one of those hothouse flower film enthusiasts who feel relieved whenever Citizen Kane comes on Turner Classic Movies, as if it were a remedy for my chronic migraine. I’m oddly grateful to Ted Turner (my undergraduate commencement speaker and an American mogul/eccentric much like Kane and Plainview) for TCM, though I find myself muttering after I’ve clicked back over to, say, some Jennifer Aniston rom-com, “What happened to Hollywood?” Sure, it’s a cliché of a question, but the answers are myriad and complicated, having mainly to do with changes in the culture and in the medium itself. There are certain images, ideas, and obsessions that are inherent to our collective identity as a nation, and every once in a great while contemporary filmmakers who happen to have the money, the talent, the connections, and the audacity, explore them with varying degrees of success. P.T. Anderson’s 2007 Oscar-winning There Will Be Blood is one if those movies, a masterpiece in the tradition of Welles’ Citizen Kane and, yes, I can without hesitation tell you that I absolutely adore it. Classic Hollywood lives on.

There Will Be Blood is loosely based on Upton Sinclair’s 1927 novel Oil! Though I haven’t read the novel, I do know that while adapting the material for his screenplay, Anderson chose to concentrate on the troubled and troubling relationship between Daniel Plainview, a self-made oilman played to perfection by a John Huston-inspired Daniel Day Lewis, and his more politically and emotionally progressive “son,” H.W., rather than the Teapot Dome Scandal of the 1920’s; it was an important and effective choice. During the first ten minutes of the film, Anderson provides us with all the exposition we’ll need through a largely dialogue-free sequence in which we’re witness to the crudity and danger of early American oil exploration, our main character’s relentless vigor and drive, and H.W.’s entrance into Plainview’s life as an infant orphaned by an oil-well accident. The final scene in the opening sequence is masterful: Daniel Plainview alone on a train with H.W. as a baby tucked into an open suitcase. H.W. plays with Daniel’s mustache as Daniel looks down on him with tenderness. Right from the start, Anderson is confounding our initial assumptions about Daniel specifically and about turn-of-the-century oilmen in general, by juxtaposing ruthlessness with familial love and loyalty. This is, after all, a movie in which conflict is created and developed via a collection of Biblical proportioned antagonisms—father v son and brother v brother. The film ultimately ends with the dissolution of any real (or imagined) family connection between Daniel and H.W. in lieu of a philosophical (and literal) battle of sorts between two conmen—Daniel Plainview the oilman, and Eli Sunday the preacher (played by the excellent Paul Dano. Dano, who can go toe-to-toe with the finest screen actor working today, is definitely one to watch.)

It’s important to pause here and mention changing views concerning the portrayal of women, minorities, the disabled, and the disenfranchised at large in American films. If we consider some of our American cinematic “masterpieces,” we often find them absent vibrant female characters, for example (think The Godfather, Citizen Kane, and Chinatown to name just three). As much as I desperately want to see my gender portrayed with respect, honesty, and integrity, many films that deal with the great American mythos don’t have much room for female characters, simply because women haven’t been a part of, and are often still excluded from, the creation story we tell ourselves—a story of brutal boots-on-the-ground capitalism and, negatively speaking, punishing exploitation. It’s a Judeo-Christian story in which the individual male forges his path through the wilderness, an anti-hero who, despite his great wealth and power, can’t overcome his subsequent moral corruption. What’s important to recognize is that the marked absence of “the other” in these films is a comment on an institutionalized patriarchy that extends beyond our everyday interactions to the very heart of our cultural mythos. There Will Be Blood is yet another film that further cements a white male-dominated American story of origin.

But what makes this particular film so thrilling is that it’s ultimately much more than a postmodern cop to an earlier American form; it’s a visceral, earnest portrayal of the forces at work in opposition to, and in support of, our American fantasy of self-sufficiency and self-reinvention. Anderson creates a highly stylized world in which a boy can seemingly spring from Plainview’s oil well, sans womb, in a sort of male Immaculate Conception. It’s a Cain and Abel world (though the twentieth century has already obscured the moral clarity of earlier epochs) where blazing fire erupts from great swaths of desert and where men, faces blacked by oil, seem to crawl up from the earth’s very crust. It’s a film that leaves us wondering which of the two “brothers” is more evil: Paul or Eli? Daniel or Henry? What I mean is, at its core, There Will Be Blood describes the convoluted love/hate relationship between capitalism and Eli Sunday’s frontier-style Christianity. Who will win in this war for men’s (and women’s, I guess) souls?

Both Daniel and Eli vie for the hearts, minds, and pocketbooks of Little Boston’s citizens, most effectively illustrated in the scenes between Daniel, Mary Sunday, and Abel Sunday—Mary and Eli’s father. Mary is really the only female character who gets any airtime in There Will Be Blood and, like the rest of the movie’s characters, she’s given a name with Biblical significance. As an innocent, she’s a likely victim and both her religious family and the faithless Daniel Plainview, attempt to use her as an example. When H.W. tells Daniel that Abel “beats her [Mary] when she doesn’t pray,” we watch Daniel’s wheels start to turn. As a slap-in-face to Eli, Daniel invites Mary to stand with him at the well’s christening, instead of allowing Eli to lead his “congregation” in prayer, and later, at the picnic, Daniel makes a point to tell Mary he’ll “protect her” from her father while Abel’s still in earshot. We could interpret Daniel’s gestures of warmth and affection toward Mary as genuine—after all, he was willing to take orphaned H.W. on as his son—but Anderson doesn’t shy away from also suggesting that Daniel is perfectly willing to use the cult of familial loyalty to win trust for financial gain—a savvy ploy we see time and time again in films like The Godfather, Chinatown, and, yes, Citizen Kane. It’s an ultimately destructive ruse and Daniel falls victim to it, naturally, in the end.

When H.W. is made deaf by another oil well accident, Daniel finds him to be a less than effective business partner, though Anderson and Day-Lewis endow the character with so much fervent contradiction, it’s hard to tell how Daniel really feels about his son’s handicap. Later, when a stranger approaches Daniel to tell him he’s his long-lost stepbrother, we can tell, in his own convoluted way, that Daniel is looking for an opportunity to trust—somebody, anybody—while he claims, of course, to have disdain for “these people.” And finally, after his own self-delusion proves, well, illusory, and he’s bereft of his “son” and his “brother,” (dispatched by his own hand, no less), we watch Daniel rage further into a kind of Charles Foster Kane-type isolation. The film closes with a terrifying scene that frankly verges on bathos (it takes place in Plainview’s private bowling alley of all places) in which Daniel forces Eli to submit, aloud, that he is “a false prophet” and that “God is a superstition” after Eli attempts to extort money from his old enemy.

Anderson has proven his tremendous potential with There Will Be Blood, so much so, I wonder how, after plumbing the bloody depths of our Great American Hang-ups, he could possibly top its achievement. It’s a difficult film and most likely not to everyone’s taste, but it’s a film I’m certain will age well thanks to its satisfying complexity and nuance. “Give me the blood,” indeed!

Best Picture Nominee Review Series: No Country For Old Men

|

| Best Picture Oscar Winner, No Country For Old Men |

Cormac McCarthy doesn’t understand women.

Statements like this are responsible for the ever-growing dent in my desk and the permanent lump on my forehead. McCarthy is a very highly respected writer. He’s won the Pulitzer Prize. He’s a MacArthur Fellow. He’s been compared to Faulkner, Joyce, and Melville. Can you even imagine a female writer garnering such acclaim without writing a single prominent male character, and then telling Oprah, “I don’t pretend to understand men”?

The Coen brothers, happy to say, make no such nonsense generalizations about 50% of humankind. Not only did they create one of my favorite female characters of all time in one of my favorite movies of all time–Frances McDormand’s Best-Actress-Oscar-winning turn as Marge Gunderson in 1996’s criminally non-Best-Picture-winning Fargo–but they often portray prominent female characters in their films: notably in Blood Simple, Raising Arizona, Burn After Reading, and last year’s True Grit.

The union of Cormac McCarthy and the Coen brothers is, aesthetically and thematically, an excellent idea. No Country For Old Men the novel, with its sparse and evocative prose, reads like a treatment for a Coen brothers film. Violence, greed, fate, and the average joe who gets caught up in criminal activity are all recurring Coen motifs, even if the unremitting bleakness leaves almost no room for their characteristic gallows humor. However, as Ira Boudway’s Salon review puts it, in the novel’s milieu “[w]omen exist mainly to show primordial attraction and inarticulate loyalty toward men; men are more at ease sawing off shotgun barrels or dressing their own bullet wounds than they are in the presence of women, children or their own emotions.”

That’s as true of the film as it is of the book. In McCarthy’s portrayal of rural West Texas, 1980, women are receptionists, secretaries, loyal wives, and not much else. A handful of women make single-scene appearances in this movie to serve coffee or give motel room keys to the three main characters: average joe Llewelyn Moss (Josh Brolin), old Sheriff Ed Tom Bell (Tommy Lee Jones, sporting a permanent worried frown that makes you want to hug him and feed him Snausages), and serial killer Anton Chigurh (a spine-tingling Javier Bardem). The only woman who really has something to do in the film is the wonderful Kelly Macdonald, whom you can witness being wonderful to the max in the terrific Boardwalk Empire (roll on fall!).

Of course, when I say “something to do,” I mean “a grand total of ten minutes’ screentime, all of it oriented to onscreen husband Brolin.” As Carla Jean Moss, Macdonald bears an expression of chronic worriment to rival Jones’s, and almost all of her scenes require her to do nothing more than fret at Brolin, asking him for guidance or expressing concern for his safety.

In a way, Carla Jean ties the film together, but she does so solely in terms of the male characters: she is the only character to share screentime with all three of the main characters (who never appear onscreen together). Occasional hints are dropped regarding her life outside of the men–“I’m used to lots of things. I work at Wal-Mart”–but, frustratingly, these are not expanded in any way. Only in her final scene does she talk about something other than Llewelyn.

Those three main characters are all men with a mission. Llewelyn’s mission is as simple as staying alive: stumbling on the scene of a drug deal gone kaput, he swipes a satchel full of cash, and in that singularly ill-thought-out action of basic greed he finds himself a hunted man, pursued by the chillingly ruthless and single-minded Chigurh. He in turn is hunted by Sheriff Bell, who is haunted by an existential crisis born of his age and sense of his own mortality. Of the three, only Chigurh operates within a clear and unambiguous moral code. Bell feels overwhelmed by the unremitting violence of his county and plans to retire, and Llewelyn dooms himself with an act of kindness (returning to the scene of the drug deal to help the wounded man who had earlier begged him for water, thus gaining the attention of his pursuers); Chigurh, though, shows no weakness or indecision, but complies fully with a set of inflexible rules.

In perhaps the movie’s most famous scene, Chigurh asks a too-observant store owner, “What’s the most you ever lost on a coin toss?” When the owner calls the toss correctly, the hitman abides by the coin’s ruling and lets him live. By allowing external cues–the sound of a toilet flushing, the ringing of a phone, the result of a coin toss–to determine his actions, Chigurh presents himself as an instrument of fate. In fact, he can be read as the personified figure of Death itself, hunting down his victims with absolute implacability, killing or sparing them on the basis of chance outcomes that invoke chaos theory and the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics.

Over the phone, Chigurh offers Llewelyn a deal: “You bring me the money, and I’ll let [Carla Jean] go. Otherwise she’s accountable, same as you.” Even after Llewelyn is dead and the money has been recovered, Chigurh’s moral code demands that he honor the terms of this deal, and he hunts down Carla Jean.

If Chigurh is, as I read him, not Death itself but a man who believes he is enacting the works of Death on earth, then Carla Jean is the one character to call him out on this. Llewelyn, the store owner, bounty hunter Carson Wells (Woody Harrelson)–all operate within Chigurh’s framework, trying to trick him or compromise with him, accepting the rules he gives them: “You need to call it. I can’t call it for you. It wouldn’t be fair.” Only Carla Jean refuses to engage, declining to call the coin toss and telling him, “It’s not the coin [that determines your actions]. It’s just you.” It’s a fascinating glimpse into her character, which remains frustratingly underdeveloped, because recognizing the arbitrary nature of the rules does not free her from them.

The film’s final scene is of now ex-Sheriff Bell talking to (or possibly at) his wife Loretta over breakfast, aimless in his retirement. He describes his dreams of his late father, who “was goin’ on ahead and he was fixin’ to make a fire somewhere out there in all that dark and all that cold, and I knew that whenever I got there he would be there. And then I woke up…” His world has no place for an older man, for a sense of morality or law as he knows it. He might well be asking himself the question Chigurh asks of Wells, moments before killing him: “If the rule you followed brought you to this, of what use was the rule?”

Fargo ends similarly, after all the action and thrills are played out, with a moment of intimacy between law officer and spouse. The tone of the two endings, however, could hardly be farther apart: Ed Tom Bell ends No Country a defeated man, adrift in a harsh and incomprehensible world, with death the only blessing on his horizon; Marge Gunderson ends Fargo smiling, sharing in her husband’s little triumph, and saying, “Two more months.” Fargo offers hope and redemption for humanity in the suggestion that there is indeed more to life than a little money, whereas the philosophy of No Country For Old Men is summed up by an old white man complaining bitterly about “the money, and the drugs…[and] children[…]with green hair and bones in their noses.”

Max Thornton is about to move halfway across the world to be a grad student. She writes words at Gay Christian Geek.

Call for Writers!

As for guidelines, reviews should be from a feminist perspective and (when applicable) focused on the films’ female characters. If you’re still not sure, take a look at reviews of the Best Picture nominees from 2010 and 2011.

We are looking for reviews of:

2009

Slumdog MillionaireThe Curious Case of Benjamin ButtonFrost/NixonMilkThe Reader

2008AtonementNo Country for Old MenMichael ClaytonThere Will Be Blood

From the Archive: Movie Review: Juno

|

| Juno |

It turns out, however, that after an initial adjustment period to the dialogue (and a question about whether the film is set in the early ‘90s), Juno turns out to be planted in a feminist worldview, and is a film that teenagers, especially, ought to see. It was thoroughly enjoyable, funny and touching. I liked it so much that I watched it again, but when I started to write about it, what I liked about the movie became all the more confusing. I loved the music, although Juno MacGuff is way hipper than I was (or am), and I saw a representation that reminded me of myself at that age. I saw a paternal relationship that I never had and a familial openness that I’ve also never had. I saw characters who I wanted as my childhood friends and family.

It turns out, however, that after an initial adjustment period to the dialogue (and a question about whether the film is set in the early ‘90s), Juno turns out to be planted in a feminist worldview, and is a film that teenagers, especially, ought to see. It was thoroughly enjoyable, funny and touching. I liked it so much that I watched it again, but when I started to write about it, what I liked about the movie became all the more confusing. I loved the music, although Juno MacGuff is way hipper than I was (or am), and I saw a representation that reminded me of myself at that age. I saw a paternal relationship that I never had and a familial openness that I’ve also never had. I saw characters who I wanted as my childhood friends and family.  The film’s real progressive moment comes when Juno realizes that her idea of perfection isn’t perfect. She realizes that a father who doesn’t want to be there would be as bad as a mother who hadn’t wanted to be there. She sees that a father isn’t a necessity–or perhaps simply that two parents aren’t a necessity. Yet what does this all add up to mean? There’s certainly a moment of female solidarity (and this isn’t the only one, certainly, in the film), and a difficult decision that she makes independently. But, as with other conclusions I’ve made, I’m left with the question of “So what?”

The film’s real progressive moment comes when Juno realizes that her idea of perfection isn’t perfect. She realizes that a father who doesn’t want to be there would be as bad as a mother who hadn’t wanted to be there. She sees that a father isn’t a necessity–or perhaps simply that two parents aren’t a necessity. Yet what does this all add up to mean? There’s certainly a moment of female solidarity (and this isn’t the only one, certainly, in the film), and a difficult decision that she makes independently. But, as with other conclusions I’ve made, I’m left with the question of “So what?”From the Archive: Business Trip Wishes

As you work toward developing this film, and if you’re at all interested in breaking some new ground by portraying real women on-screen (rather than the conventional stereotypes of women we’ve gotten so used to seeing) please be advised of the following:

1. Do not cast Jessica Alba, Megan Fox, Katherine Heigl, and Anna Faris, and then parade them around in giant heels, wearing some semblance of revealing business suit-esque attire, probably involving excessive cleavage and certainly showcasing thirty gratuitous inches of bare leg.

11. Do not turn this into Sex and the City Takes a Business Trip, even though that’s undoubtedly what everyone will encourage you to do.

Good luck!

Director Spotlight: Tanya Hamilton

|

| Filmmaker Tanya Hamilton |

There aren’t a lot of black women making movies, which I find interesting in a way. I’ve blindly not really thought of it. I’m race obsessed, and that has been the lens through which I walk through the world. Making the film has made me think about my gender in a way I had previously not bothered [to]. Film is a very male-dominated world, and those positions are very protected. I think it’s interesting in terms of what gets defined as a woman’s film as opposed to a regular film. I haven’t figured it out yet. I don’t have a theory — at least not a smart one.

One is a thriller/love story set in Jamaica during a violent election. The other is a film about two brothers in fledgling Native American tribe building their first casino and confronting the unforgiving world of D.C. politics to achieve their goal.

|

| Night Catches Us |

In the summer of ’76, as President Jimmy Carter pledges to give government back to the people, tensions run high in a working-class Philadelphia neighborhood where the Black Panthers once flourished. When Marcus returns—having bolted years earlier—his homecoming isn’t exactly met with fanfare. His former movement brothers blame him for an unspeakable betrayal. Only his best friend’s widow, Patricia, appreciates Marcus’s predicament, which both unites and paralyzes them. As Patricia’s daughter compels the two comrades to confront their past, history repeats itself in dangerous ways.

Refusing to romanticize Black Power, Hamilton chooses the riskier path of examining its emotional and political fallout. The bullet holes and bloodstains that Iris uncovers after peeling away a strip of wallpaper at home suggest that her father died not as a martyr for the cause but as yet another senseless casualty in an endless conflict, with police harassment of African-Americans by the nearly all-white Philly force still continuing in ’76. Jimmy’s parroting of black macho, in turn, leads only to more spilled blood.

Hamilton doesn’t rush to supply answers. She lets her mesmerizing movie sneak up on you and seep in until you feel it in your bones. The fact that Hamilton studied painting at Cooper Union helps the images resonate, as does the haunting lighting supplied by cinematographer David Tumblety. Add a terrific score supplied by the Roots and the movie has you in its grip. Mackie and Washington could not be better; they had me at hello. Night Catches Us is essentially a ghost story, with the past persistently intruding on the present. Hamilton manifests her vision of what politics can do to individual thinking with subtlety and sophistication. Remember her name. She’s a genuine find.

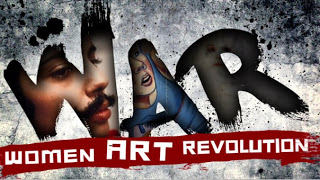

Preview: !Women Art Revolution

|

| !Women Art Revolution |

From the official movie website:

!Women Art Revolution elaborates the relationship of the Feminist Art Movement to the 1960s anti-war and civil rights movements and explains how historical events, such as the all-male protest exhibition against the invasion of Cambodia, sparked the first of many feminist actions against major cultural institutions. The film details major developments in women’s art of the 1970s, including the first feminist art education programs, political organizations and protests, alternative art spaces such as the A.I.R. Gallery and Franklin Furnace in New York and the Los Angeles Women’s Building, publications such as Chrysalis and Heresies, and landmark exhibitions, performances, and installations of public art that changed the entire direction of art.

Watch the trailer:

Just for fun, here’s the other poster:

Let us know if you have seen or plan to see this film!

Guest Writer Wednesday: Easy A: A Fauxminist Film

|

| Emma Stone stars in Easy A |