This is a guest post by Shay Revolver. Spoilers and Trigger Warning for discussions of rape.

The 90s were a confusing time for pre- and full-on teenage girls. The 80s teen flick era had ended and left us a legacy of lessons on male-female relations that was nowhere near empowering. Mostly girls learned that if a guy really loves you then he’s got to stalk you to show it, and if you love him you’d better take off those glasses and ditch that ponytail. That was the extent of teen girl roles in movies; we were objects and trophies. When the 90s rolled around, girl power (pre-Spice Girls) was bubbling under the skin of society, and we were about to boil over. There are a few movies that I can think of that hinted at the dawning of the age of girlquarius, where teenage girls were thinking for themselves, acting how they wanted, living on screen on their own terms.

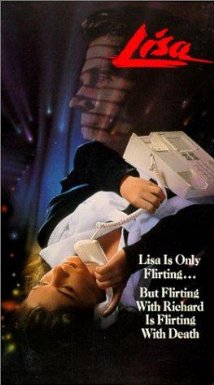

I’ve recently taken to revisiting some of these forgotten (or culty, depending on who’s looking) classics with a new, more grown-up and feminist eye, and I’ve been examining the lessons that each of these gems showed us. One of my recent new/old film crushes is a 1990 film called Lisa (starring Cheryl Ladd, Staci Keenan, and DW Moffet). It has all the teen angst that a gal could hope for. At first glance you expect this to be a typical thriller, but this film is so much more. It is an open exploration of a young woman coming into her own, exploring her sexuality, rebelling against traditional convention, and if that weren’t interesting enough, Lisa’s story runs parallel to the exploits of a serial rapist/killer. One of the things that makes this film so different is the point at which these two stories intersect, and Lisa proves herself more capable than imaginable and saves herself and her mother from the killer’s clutches. The ending of the film flipped the traditional damsel in distress cliché on its head.

In case you missed this one, Lisa is the story of a super curious 14-year-old girl named Lisa Holland. Lisa has started growing into her sexuality and, like many teenage heterosexual girls, she is more than a little boy crazy. Her sexual awakening is made more complicated by the fact that her mother, Katherine, a single mom who had Lisa at 15 and has raised her on her own, is having no part of Lisa dating–until she’s 16. Katherine understandably doesn’t want her daughter to make the same mistakes, and she is worried that dating will lead to sex, which might lead to her daughter ending up being a single mom. Most films would have taken this situation and made sure that the mother has a horrible life, thoroughly punishing her for her choice to have premarital sex. Instead, the writer and director take a rare approach to female yearnings and desires. The mother comes off sympathetic; she gives guidance more than criticism. There is also no slut shaming. Her mother actually acknowledges that her daughter has these very natural urges. At first glance, the conversations between them might come off as an all-out attempt at suppressing Lisa’s sexuality, but the way it is handled is beautiful. Her mother is honest with her reasoning and is very clear that she feels her daughter is too young to have sex. The openness attached to their conversations is refreshing, and it is kind of nice to see a young woman trying to come to terms with her feelings and sexuality. Katherine, in her role as single mother and successful working woman, who didn’t end up a statistic despite being a young single mother, is even involved in a relationship. She straddles a line, however, and keeps it from her daughter in an effort to protect her.

Lisa’s best friend is another young woman named Wendy Marks. There is a beautiful contrast between the two of them. Wendy’s parents aren’t as strict as Lisa’s mother. Wendy is allowed to date, and Lisa is fascinated. Having all of these new feelings and no outlet or experience, Lisa creates a fantasy world in which she can express herself and explore these new feelings. She and her friend Wendy keep a scrapbook of men that they see and would like to date, much like the heart covered Mr * Mrs. (or Mrs. & Mrs.) notebook that many of us had when we were growing up. Lisa and her friend Wendy see men they like and follow them to gain more information about them. Sometimes they even phone the men and record their intel in the scrapbook. This notebook helps Lisa explore new feelings in a more private way and allows her to explore the qualities that she wants her future beau to have. She gains her outlet and comes to an understanding of her sexuality and, in some ways, her relationship desires. I also found it lovely that while the girls’ budding sexuality is growing at different rates there is no pressure to compete or follow or judge.

All of these explorations combined with a protagonist portrayed by a young woman trying to figure out relationships and sexuality would have been more than enough to satiate my wish list for a good film, but this thriller threw in a serial rapist and murderer dubbed The Candlelight Killer, who stalks women and then calls and kills them after discovering where they live. This added a whole new level to the film. First of all, the film does something super rare; the rapist isn’t some worn, wrinkled , unattractive guy who can’t get a date. Richard, played by DW Moffett, is a hottie. It highlights a fact that is often overlooked in these types of characters when they are portrayed on TV or film: rape isn’t about a guy who can’t get a date, or about a woman being an undercover seductress who was asking for it. Rape is about power and hatred of women. This fact is reinforced by the psychological torture that Richard inflicts upon these women before he rapes and ultimately brutally murders them. He leaves messages on their answering machine telling them that he is in their house and announces his plans to kill them. He strips these women of the safety that their homes are supposed to provide. It is a clear, honest portrayal–and a parallel to rape itself. Having such a violation of sexuality portrayed in a storyline that runs parallel to the story of Lisa’s budding sexuality is an odd but brilliant choice. It doesn’t just use the message that all men are monsters, or blame the victims for their beauty taunting him. They portray this heinous crime as what it is: an attempt to remove a woman’s power.

You can pretty much see where the story is headed. Richard is going to end up in Lisa’s scrapbook, and she will be punished for her desires. Of course you would think that because that’s the message we’ve been shown. Good girls have no desires; if you have them you will be punished. I would have thought it too, but this film has already bucked every trend. You’ve got an attractive rapist, a former teen mom who is successful and raising a brilliant daughter, and a young woman having her budding sexuality acknowledged. When the stories intersect, they continue this realistic trend. Lisa accidentally bumps into Richard when he’s coming from a kill. He aids her and flirts with her a little bit, and she awkwardly flirts back, making him scrapbook worthy. She goes about her usual routine, follows him and gathers his license plate number and uses that to track him down and get his phone number from the DMV. After another failed attempt at bypassing her mother’s bothersome no-dating rule, she has to turn down a chance for a double date with Wendy and a boy her own age. Lisa locks herself in her room and decides to call Richard. She flirts with him some more, pretending she’s an older woman, and she piques his interest.

Lisa keeps up her game, and with Wendy’s help, she continues to stalk him, which isn’t that smart of an idea, but it is age appropriate and realistic. She even continues her phone conversations after nearly getting caught. The plot progresses as Lisa reveals more and more about herself with every conversation, and soon Lisa realizes her game is going to have to end because Richard begins to push for a face-to-face meeting. The film doesn’t shy away from the more manipulative ways of teenage girls, but it gives a rationale and adds method and logic to the madness. There is no right or wrong, but a whole lot of gray. There is no punishment for Lisa’s actions per se; her actions do cause her mother to become Richard’s next and final victim. But, the film doesn’t end as bad as it could have. Katherine doesn’t get killed. Lisa isn’t punished for having desires or growing up and trying to figure out who she is going to be as a woman. After sneaking away to go on a trip, Lisa returns just in time to see the stage set for her mother’s murder at the hands of The Candlelight Killer, and she is forced to defend her life and the life of her unconscious mother. She doesn’t play damsel in distress or fall down the stairs; she chooses to fight, and even though she doesn’t initially come out on top, her mother wakes in time to come to her aid. The fight and movie ends with Richard going out of the window thanks to a handy baseball bat and the women holding each other in solidarity and love.

There are so many things about Lisa that make it interesting. The honest portrayal of a young woman’s burgeoning womanhood. The open expression of Lisa’s sexuality and desires. The over protectiveness of a single mother that truly rides a fine line between cautionary and plot building without delving into the gray area of slut shaming, a teen pregnancy, or portraying the mother as a failure whose life went wrong because she had sex at a young age. All in all this film , even at its campiest, showed strong women, and in the end, Lisa and her mother saved themselves from the clutches of the killer. They relied on each other to overcome the situation; there were no cops or men rushing to their rescue. And, there is something super awesome about watching two women surviving after killing a serial killer/rapist. Thank you Lisa for giving us a movie that didn’t shame young women for having urges and desires but instead giving us a movie that showed life as it often is: filled with areas of gray. Lisa showed independence and strength in the face of danger. And there is something truly beautiful about a young woman coming into her own, making and learning from her mistakes.

Shay Revolver is a vegan, feminist, cinephile, insomniac , recovering NYU student and former roller derby player currently working as a NY-based microcinema filmmaker, web series creator and writer. She’s obsessed with most books , especially the Pop Culture and Philosophy series and loves movies and TV shows from low brow to high class. As long as the image is moving she’s all in and believes that everything is worth a watch. She still believes that movies make the best bedtime stories because books are a daytime activity to rev up your engine and once you flip that first page, you have to keep going until you finish it and that is beautiful in its own right. She enjoys talking about the feminist perspective in comic book and gaming culture and the lack of gender equality in main stream cinema and television productions.. Twitter @socialslumber13