This guest post by Emma Houxbois appears as part of our theme week on Sex Positivity.

Sex positivity, as a movement and concept in general, is open to a great deal of interpretation and criticism because of the multitude of forms that it’s taken over the years. Nowhere is that more apparent than in the heated debates that formed what are alternately described as “the feminist sex wars” and “lesbian sex wars” in establishing where the boundaries between legitimate self expression and exploitation lie in areas like commercial pornography and BDSM lie.

Discussions of power, privilege, and control typically remain central to the topic of sex positivity, and they’re vitally important when considering film in particular, a medium where female expressions of desire are more often than not conceived of and executed by men. While these discussions are vital, they can also stand to be expanded into what sex positivity can look like when it moves beyond the idea of liberating self-expression to recognizing and understanding other people’s desires.

Prior to the debut of Sense 8, Lana and Andy Wachowski were not typically considered to be filmmakers with a particularly sex positive agenda, but the roots of their broad and inclusive conceptions of sexuality in their Netflix series (co-created with J. Michael Straczynski) go all the way back to their debut Bound, a heist flick that starred Gina Gershon and Jennifer Tilly as lovers. At the time, the Wachowskis reached out to erotica writer and famed proponent of sex positive femininity Susie Bright to offer her a cameo in the film as thanks for her work’s influence in creating the film. Bright, who fell in love with the script, countered with a readily accepted offer to be their consultant on film and provide direction on how to film the sex scenes between Gershon and Tilly.

It’s an under-discussed part of the Wachowskis’ career that Bound, through arrangements made by Bright, had its debut at the San Francisco Gay and Lesbian Film Festival at the Castro theater, establishing a queer context to their work years before Lana came out as transgender. However it’s easy to see a recapturing of the spirit of their collaboration with Bright in Sense8, as they expand from the lesbian romance of Bound to expand into a multitude of simultaneous expressions of sexuality.

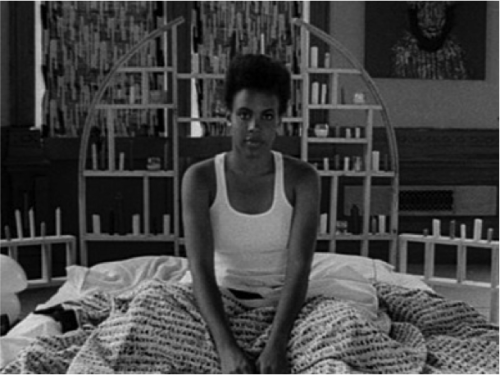

Key to much of the conversation around the series and its depiction of sex is how central, and explicit, the relationship between Nomi, a trans woman, (played by Jamie Clayton) and her girlfriend Amanita (played by Freema Agyeman) is. In and of itself it’s a tremendous victory for trans representation that scores the unheard of trifecta of a trans woman character being played by an actual trans actress, recognizes that trans women experience same gender desire, and doesn’t construct her sexuality around deception of any kind. The Wachowskis clearly communicate their triumph in this with the close up shot of a well-lubricated rainbow dildo dropping to the floor at the close of their first sex scene together, but Sense8 sets out to accomplish far more than just a sex toy mic drop.

In addition to Nomi and Amanita’s relationship, the series develops the romance between closeted Mexican actor Lito Rodriguez (played by Miguel Angel Silvestre) who is among the seven other characters Nomi shares an empathic bond with, and his boyfriend Hernando, as well as blossoming heterosexual romances between other members of the group. Nomi and Lito’s relationships are given the bulk of the development as the series progresses, but the Wachowskis use that focus as an opportunity to build a conception of sex that celebrates differentiation while also tapping into the universal aspects of sex and intimacy that everyone experiences regardless of gender or orientation.

This is primarily and most noticeably achieved in a sequence in the sixth episode where enough of the emotional energy of the sensates is focused on sex to trigger a full blown orgy between several of them, including Nomi, Lito, and two of the straight male characters. The focus and direction of the sequence, which was described by Silvestre as Lana Wachowski yelling directions from the sideline, which sounds much like what Bright believed her role in Bound’s production would be interpreted as. (“I think they imagined that meant I stood over Gina and Jennifer with a riding crop, snapping, “Deeper , Harder, A Little to the Left!”) But the scene does also communicate the same language and visuals that Bright intended for Bound:

“There were two main ideas on my mind. One, unlike most Hollywood lesbian scenarios, this movie shouldn’t insinuate oral sex– that’s not the kind of characters we were looking at. BOUND is about getting inside someone very fast, trusting them with everything-these women had to be fucking each other. Penetration was the act we wanted to imply. Yet obviously we weren’t going to get away with gynecological or hardcore shots in a movie that was headed for America’s shopping malls.”

“My idea, stolen from the ‘Kathy’ footage, was that we show a woman’s legs, straining and squeezing, and that we see that her lover’s forearm between her thighs. We dwell on that arm for a moment, moving back and forth in a fucking rhythm, looking sure, steady and unrelenting. Then, instead of following her arm all the way up to her lover’s pussy, we would cut to her stomach, fluttering like a little butterfly in that spasm we all recognize as orgasm. I loved the idea of eroticizing a woman’s belly like that. A lot of men making sex movies try to show a woman’s sexual pleasure by focusing the lens on her cleavage. Maybe that’s what they’re looking at, but hey, there’s a lot more going on!

“The other key idea was to eroticize the women’s hands whenever they were flirting or making love with each other. ‘A lesbian’s hands are her cock, they’re the hard-on of the movie, that’s what you want to follow,’ I said, like some veteran pornographer. When I see Corky’s hands on screen, I want to imagine how they would feel inside me. They’re the metaphorical substitute for the genital shots that you won’t be showing.”

Eroticizing the hands is the technique most keenly felt that follows through from Bound, but toward a somewhat different purpose in Sense8. Bright was looking for a way to get the idea of the kind of sex she imagined being most relevant to the plot and character beats of Bound across without being able to use explicit detail. She wanted to communicate genuine queer female desire to an audience who had never seen it presented in a manner equal to the depiction of straight sex in mainstream film. In Sense8, the first thing that focusing on eroticizing hands and grasping does is communicate the universality of desire across characters who identify as gay, lesbian, and straight. It depicts a physical element of sex that everyone, no matter their gender or orientation, can easily grasp and identify with. What it also does, just as Bright sought to evoke penetration in the sex scenes as part of the overall themes of Bound, is communicate how the individual sensates have been grasping toward each other in the series, trying to reach an understanding of their circumstances and who each other are.

Differentiation cannot be overlooked as being a major component of how the series presents and celebrates sexuality, despite the centrality of the “orgy” sequence that communicates a universality to human desire. Immediately following that sequence is a conversation in which Nomi tries to make sense of why she shares an empathic bond with the others, stating that it would seem more logical to her if the others were closer and not further from her identity and experiences. The response from Amanita’s mother is that she teaches the importance of differentiation through her classes on evolution. The implicit idea is that if differentiation is a key catalyst in biological evolution, it cannot be overlooked when considering the evolution of attitudes around sex that include queer and trans experiences.

Elsewhere in the series we see the critical importance of differentiation outside of sex, most notably as Lito and Wolfgang trade places in each others’ lives at the climax of their individual storylines. Lito, having pushed the situation with his blackmailer as far as he can by acting, falls back on Wolfgang to literally finish the fight. Then Wolfgang, having reached the limits of his skills as a thief and fighter in dealing with his rival, allows Lito to step forward and ply his trade as an actor. Each facet of the characters’ lives and experiences are as vital to the others’ towards their shared survival whether it be Sun’s martial arts skills, Capheus’ driving abilities, Lito’s acting skills, or Nomi’s computer wizardry.

The net effect, woven throughout the series, is a sex positivity that both embraces differentiation and recognizes the universal experiences that can work to close gaps of gender, orientation, and race that routinely stymie the discourse.

See Also: “The American Lens on Global Unity in Sense8,” “Jupiter Ascending: Female Centered Fantasy That’s Not Quite Feminist”

Emma Houxbois is a fiercely queer trans woman whose natural habitat is the Pacific Northwest. She is currently the Comics Editor for The Rainbow Hub and co-host of Fantheon, a weekly comics podcast.