This guest post by Jessica Freeman-Slade appears as part of our theme week on Female Friendship.

In her bestselling collection Bad Feminist, Roxane Gay starts the listicle entitled “How to Be Friends with Another Woman” with this as the very first item: “Abandon the cultural myth that all female friendships must be bitchy, toxic, or competitive. This myth is like heels and purses—pretty but designed to SLOW women down.”

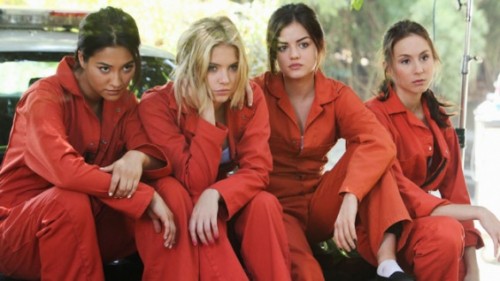

Pretty Little Liars, a show on ABC Family that just wrapped its fifth season, looks on the surface to be all about the things that slow female friendships down, especially in high school—the fabulous heels, the purses, the toxicity of secret-keeping and back-stabbing. (For a long time I assumed it was Gossip Girl in suburbia, all about teenagers behaving badly and looking great while doing it.) Yet upon closer inspection, it presents itself as the most radical show about women, and specifically female friendship, on television, a treatise on what might happen when four friends refuse to become mean girls, and choose something to embark on something far more difficult: genuine support of each other. That might explain why the show is the most Tweeted-about series of all time (yes, surpassing Scandal, with 11.7 million Tweets sent during its season 2 finale in 2013), and why it’s proven to be much more than just a pretty teenage drama.

Based upon the YA series by Sara Shepard, PLL takes place in the fictional town of Rosewood, Pennsylvania, where queen bee Alison (Sasha Pieterse) has been missing for almost a year, and her formerly tight clique has broken up as they enter their junior year of high school. Star swimmer Emily (Shay Mitchell), who once nursed a deeply closeted crush on Alison, is just starting to assert her sexuality and independence. Straight-A student Spencer (Troian Bellisario) is tiptoeing around her uber-competitive sister Melissa (Torrey DeVitto). The fashionista Hanna (Ashley Benson) spends most of her time shoplifting and looking the other way while her single mother cleans up her messes. And artistic Aria (Lucy Hale) has just returned from a year abroad with her family, and immediately falls for Ezra (Ian Harding), a cute guy who—tada!—turns out to be her English teacher. These characters seem like archetypes (jock, Type-A, ditz, flower child) with very little beyond typical teenage drama to concern them. But then Alison’s dead body is discovered, and the girls start receiving texts from a mysterious “A” who seems to know all their unflattering secrets, lies, and desires, and worst, the details that could easily nail them for a terrible crime. But rather than turn away from each other, the girls immediately come back together, breaking those archetypes open and forming an alliance to uncover their texting tormentor and bring Alison’s killer to justice. As its millions of rabidly texting fans would attest, Pretty Little Liars has become the rare teen-oriented show that embraces all types of girls, the importance of supporting your friends and how they choose to be happy, and most importantly, how to fight against a bully who keeps you down.

Initially it seems that the villain is the mysterious “A,” whose threats scare the girls into silence or keep them at a distance from what makes them happy. (One of the gentler A threats is in Season 1, when A steals photographs of Emily kissing her new girlfriend and threatens to reveal them to her family.) But the real spectre of terror over the entire series is Alison: the glamorous, manipulative, power-hungry, and freakishly intelligent teenage girl who can bend anybody to her will.

In life, Alison bullied and teased her so-called friends and kept them from showing their own strengths. Hanna in particular withered under her rule, as Alison called her “Hefty Hanna” until she became bulimic. And even after death, the secrets that Alison had kept for the girls serve as A’s material for ripping their lives apart—to reveal Aria’s relationship with Ezra as well as her father’s (Chad Lowe) infidelity, to expose Spencer’s plagiarism of an award-winning essay, and to send Hanna’s mother to jail for stealing money as they’re on the verge of foreclosure. The villainy at the core of PLL is Alison’s undue influence, the one cool girl who rules over other girls and takes away their power.

But instead of becoming more like their tormentor, Pretty Little Liars gives its characters the choice of telling the truth, trusting each other, and taking on the consequences of their mistakes rather than lying their way out of them. Aria confronts her father about the infidelity, and Spencer withdraws her essay from the competition and disappoints her family in the process. Emily comes out of the closet, despite her fears—and her friends are genuinely happy and supportive of her. And to earn back the balance of her mother’s stolen money, on A’s orders Hanna consumes a dozen cupcakes, triggering a flashback to her days of binge eating. Yet when A texts her to do what Alison taught her, to “get rid of it,” Hanna refuses to go down the same old road. Instead of becoming more like Alison, the girls decide to become more like themselves, the selves that they know to be powerful and beautiful, inside and out.

Let’s revisit that #1 rule of female friendship from Roxane Gay—too often we ascribe a kind of inherent toxicity to female friendship, to the way women negotiate power dynamics and competition amongst themselves, as though there was a finite amount of beauty, intelligence, and influence in the room. The perpetuation of “girl-on-girl” crime doesn’t have as much to do with actual criminality or offense (when a cheating boyfriend is caught, why do we blame the other woman?), as it does with the notion that only one girl can win at any given moment. Yet in embracing the differences of the four Liars, the show allows a kind of multiplicity in its portraits of good girls who are not goodie two-shoes, and what winning in a community of women can look like. These girls kick butt together, and they do it with strengths drawn directly from their personalities, without the supernatural powers or exceptionally strong kickboxing or archery skills that we expect from other heroines of pop culture. For Emily, it’s her disarming honesty and candor that allows people to trust and open up to her.

Aria is small but fierce, and her wisdom beyond her years empowers her to make decisions that she can stand by.

Hanna is loyal to the core, and because she herself had been an outsider, she refuses to tolerate deceit from the people around her.

And for Spencer, in a constantly evolving and Emmy-worth performance by Bellisario, it’s her supreme intelligence and drive makes her the perfect troop leader, galvanizing her friends to stop settling for misery and start exposing the threats around them.

To be sure, the show has plenty of faults: the various relationship between teenage girls and some much-older love interests gives me plenty of heebie-jeebies, as do the increasingly improbable plot twists and the immaculate wardrobe, hair, and makeup choices on display at all times. (When, in all that mystery solving and running around in the woods, do they have enough time to pick out such cute outfits?) And, if you agree with A.O. Scott’s recent handwringing over the “death of adulthood” in contemporary media, you might wonder why so much of this positive friendship conversation has to be about teenagers rather than grown women. But these girls are exactly at the age where major decisions about character are made—when you move from childhood into adulthood, you stop absorbing information from your role models and start making your own choices. And the choice—to be a mean girl, and rule over everyone else, or to be a kind girl and to form meaningful relationships—is at the very center of Pretty Little Liars.

Most importantly, the stakes for these friendships are truly, massively high. These girls are literally saving each other FROM DEATH—breaking each other out of cages, chasing down bad guys, and fighting back against people who would like to silence them. While the plotting of the show may be highly tongue-in-cheek in treating death-defying an extracurricular activity, you have to admire how high the stakes have been placed. Without having each other’s backs, without their friendships, these girls would be dead—friendship is not only a positive choice, it is a lifesaving choice. And that is a pretty darn heroic proposition, especially for teenage girls.

Jessica Freeman-Slade is a cookbook editor at Random House, and has written reviews for The Rumpus, The Millions, The TK Review, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and Specter Magazine, among others. She lives in Morningside Heights, NY.