Written by Leigh Kolb

The Punk Singer, the Sini Anderson-directed Kathleen Hanna documentary released Nov. 30, is ostensibly about Hanna–the iconic feminist and punk artist, and iconic feminist punk artist. It is also, however, about the power of women collaborating. From Kathy Acker’s advice to Tobi Vail and Kathi Wilcox’s encouragement to Johanna Fateman’s zines and friendship, Hanna’s career trajectory from feminist punk singer to feminist pop singer to her current project, The Julie Ruin (a perfect combination of feminist punk and pop), has been shaped by female creative power and collaboration.

Hanna stresses the importance of not only girls’ individual power and creativity, but also the need for us to talk–and sing–to one another and to truly listen and believe. This is something that feminism consistently struggles with.

A sexist USA Today article by a female reporter about Bikini Kill and riot grrrl from the early 1990s was featured as a turning point in Hannah’s career. Hanna and her bandmates began a press blackout after the USA Today article and other mainstream press outlets framed the band and the movement around the performers’ bodies and clothes and focused in on their sexuality/sexual pasts.

How disappointing, then, that an NPR article about the new documentary and her project’s new album (The Julie Ruin’s Run Fast), leads with her “bra and panties” past, sexual abuse, and her looks (“She’s striking, with her jet-black hair, oval Modigliani face, pale Liz Taylor eyes…”). Even a Bitch Media reviewer says, while analyzing how riot grrrl was exclusive to white women, that Hanna’s beauty is “the elephant in the room” in the film (“She is one drop-dead-gorgeous-looking woman, both as a teenager and now as an adult. I would argue that it was her physical attractiveness helped her music get mainstream attention”).

Most interviews and reviews have steered clear of focusing on Hanna’s physicality and sexuality, thankfully, but it’s still disheartening and distracting to see any publication bringing up her looks as a source of commentary (and both are by female journalists). Indeed, the media blackout that Bikini Kill led in the 1990s isn’t needed now–Hanna brings up the changed media landscape in multiple interviews–and Hanna has been granting a great number of interviews in recent months as a lead-up to The Punk Singer and Run Fast.

[youtube_sc url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fwrXC5OXqgc”]

We are lucky to be hearing Hanna’s voice as much as we are. She was diagnosed with late-stage Lyme disease in 2010 after suffering without a diagnosis for six years. The Punk Singer spends a great deal of time chronicling her illness–how it ended her musical career after Le Tigre (she says that she made the excuse that she was done with her music because she had nothing left to say instead of facing that she might not be able to do what she loved so much anymore).

The Punk Singer is a powerful showcase of the last three decades of not only Hanna’s life, but also the relationships and collaborations that shaped a generation of third-wave feminists and beyond. Footage from live performances and interviews, and personal films/photos are interwoven with interviews from Hanna’s contemporaries, bandmates, and journalists to tell a story about a feminist icon and a movement that would shape the future of music and feminism. Lynn Breedlove, Ann Powers, Corin Tucker, Kim Gordon, Joan Jett, and Adam Horovitz (her husband), among others, add powerful reflections to the history of the riot grrrl movement and Hanna’s professional and personal life.

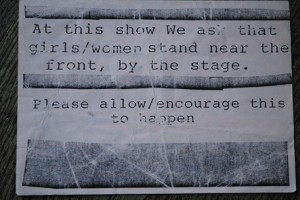

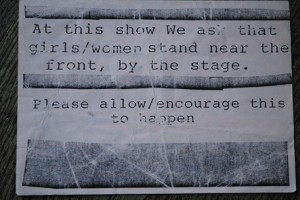

The term riot grrrl itself had its origins in collaboration–Jen Smith (of Bratmobile and The Quails) talked about the need for a girl riot, and Bikini Kill’s Tobi Vail wrote about angry grrrls. The two terms combined to name a movement of in-your-face feminist punk music that fought against patriarchy and sexual assault with the motto “girls to the front” defining the ideology and the concert space–which was/is often a masculine, hostile space for women.

Breedlove–who provided some of the most poignant sound bites in the film–says that riot grrrl was about “girls going back to their girlhood… reclaiming their girlhood,” and pledging to “relive” their girlhood with power. Perhaps that’s one of the reasons that so many of us can plug in a Bikini Kill album at 20, 30, 40 and beyond, and feel catapulted back into a poster-filled bedroom, imagining ourselves as girls with power and strength, and revising our histories inside and outside of our girlhood rooms.

The goal of riot grrrl, Hanna and others in the DC-based movement said, was that women anywhere could take it and “run with it”–making it mean what it needed to mean for them. This one-flexible-size-fits-all goal of feminist activism is often difficult to actually manage, but for a moment in the 90s, there was a worthy effort. The repeated importance of fanzines highlights the importance of both collaboration and women’s authentic voices (even ones with “Valley Girl” accents).

The effort of the waves of feminism are highlighted in the documentary in a brief foray into history. While short and somewhat superficial (which is appropriate for the scope of the film), it was interesting and important that the coverage of first- and second-wave feminism noted that women “turned race consciousness on themselves” during the abolitionist movement of the first wave and the civil rights movement of the second wave. Savvy viewers will take that and understand what that means to the historical context of Western feminism (a meaning that is complex and problematic).

Collaboration hasn’t been a strong point for feminists throughout history. The air of critique surrounding Hanna’s beauty and privilege combined with the relative whiteness of riot grrrl both serve to create divisions and otherness within our own ranks. The job of this documentary isn’t to serve as an investigative piece into the beautiful whiteness of feminism–it’s to tell the story of one woman and her personal, professional, and political past and present.

When Bikini Kill broke up in 1997, Hanna recorded the album Julie Ruin under an assumed name (to “escape” what had happened to her in prior years–the bad, sexist press, the threats, the physical attacks).

Hanna says that in Bikini Kill, she was singing to the “elusive asshole” male. With Julie Ruin, she wanted to “start singing directly to other women.” She recorded the entire album in her bedroom, which she points out was purposeful and meaningful. She says that girls’ bedrooms are spaces of “creativity” and great power–but these rooms are set apart from one another; girls have this creativity and personhood in separated, “cut out” spaces. She wanted her album to feel like it was from a girl in her bedroom to girls in their bedrooms, and she succeeded.

She went on to form bands and perform with Le Tigre and The Julie Ruin, constantly revising and evolving the concept of feminist art and performance.

Throughout the documentary, Virginia Woolf’s words kept ringing in my ears–that women need “a room of one’s own” to create and be independent. For too long, women who have had the undeniable privilege of having rooms of their own have been doing so behind closed doors, apart from one another, as Hanna talks about in regard to Julie Ruin and how girls have these safe, powerful spaces that are set apart from one another.

And as Breedlove points out, the beauty of riot grrrl lies in the fact that we do get to remake our girlhoods, inserting anger and rioting where before there was quiet sadness and loneliness. It’s easy to flip back and forth between Bikini Kill and The Julie Ruin (and everything in between) and be catapulted back to a moment or into a moment. This idea that we can rewrite our histories and revise our futures by pressing “play” is woven throughout The Punk Singer. Creating ourselves in our rooms, and then stepping outside of our rooms and talking to one another and listening to one another is essential.

Continuous moving–rioting, dancing, singing, shouting, collaborating–is how we will survive and thrive, just as Hanna has. Her contributions to feminism and feminist culture (and great music) are undeniable, and The Punk Singer does a beautiful job of inviting us into her room, and making it our own.

The Punk Singer is available on Video on Demand and in select theaters.

Recommended Links: Interview with Kathleen Hanna on the Strength It Takes to Get On Stage, by Sarah Mirk at Bitch Media; Forget ’empowered’ pop stars–we need more riot grrrls, by Daisy Buchanan at The Guardian; Punk Icon Kathleen Hanna Brings Riot Grrl Back To The Spotlight, by Katherine Brooks at The Huffington Post; 13 Reasons Every Feminist Needs To Watch “The Punk Singer,” by Ariane Lange at Buzzfeed; Film Review: ‘The Punk Singer,’ by Dennis Harvey at Variety; Q. & A. Kathleen Hanna on Love, Illness and the Life-Affirming Joy of Punk Rock, by Matt Diehl at The New York Times; Kathleen Hanna and ‘The Punk Singer’ Director On New Doc, Riot Grrl and Why People Hate on Feminism, by Bryce J. Renniger at Indiewire; Riot Grrrl in the Media Timeline at Feminist Memory; Kathleen Hanna Reading “The Riot Grrrl Manifesto” at Henry Review; Don’t Need You – The Herstory of Riot Grrrl

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.