|

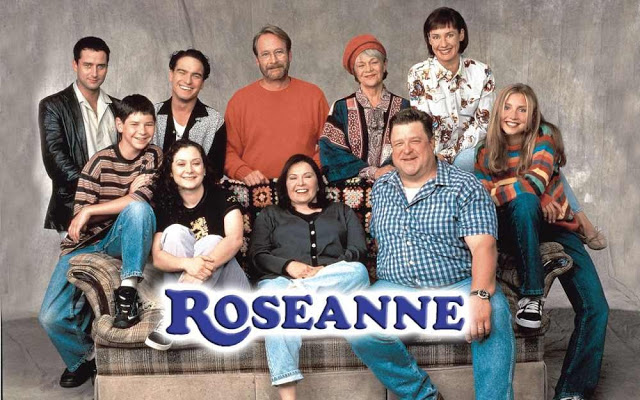

| The cast of Roseanne |

I grew up watching

Roseanne. The show first aired in 1988—when I was ten years old—and it ended after 9 seasons, around the time I graduated high school. The fact that the show now appears in reruns on various television stations, during all hours of the day and night, often makes me feel like the Conners have never

not been a part of my life. I saw myself (and my family) in that show, and I identified with the characters and their struggles, particularly surrounding financial issues and social status.

Unfortunately, families like the Conners just don’t exist on TV now, which is extremely problematic considering families today—and women in particular—continue to feel the never-ending effects of Wall Street tanking our economy. We simply no longer see the realities of women’s lives accurately reflected back at us in the media. In fact, I’d go as far as to say that Roseanne, a television show starring a fat, working-class, unapologetically outspoken matriarch; a television show that effectively dealt with racism, classism, feminism, gay marriage (depicting the very first gay marriage in the history of television); a television show openly addressing sexism and misogyny, and yes—a woman’s right to choose; and finally, a television show that first aired nearly 25 years ago, is a far more progressive television show than anything currently gracing the network airwaves in 2012.

I grew up in Middletown, Ohio—a small town that very recently made the Forbes’ Top Ten List of Fastest Dying Towns—and the characters on Roseanne appeared all around me in my day-to-day life in the form of factory workers, cashiers, fast-food employees, friends and family members who lived in trailer parks, those of us graduating from high school who had no idea how we’d ever pay for college, and those struggling to pay bills in a community that didn’t offer much in terms of employment opportunities aside from the local steel mill, where a majority of our parents worked. I especially identified with Darlene, who I watched morph from a snarky young tomboy who played basketball and had a close relationship with her father, into a successful young woman with a college degree who fought for animal rights, never let men control her life (unlike her older sister Becky), and who ultimately ended up with the same strong personality traits as her mother Roseanne, even though their relationship suffered through serious rough patches over the years.

|

| Roseanne working as a server |

While I managed to leave Middletown, Ohio and attend college, (by taking out a shitload of student loans) most of my family still lives there, and over the years I’ve been forced to watch my hometown crumble (literally, businesses are falling the fuck apart) like so many other Midwestern cities that’ve been ignored by our government and taken advantage of by big banks and Wall Street tycoons. I suppose my inability to identify with most characters, families, and storylines on current network television led me to begin my Netflix marathon of Roseanne last year. I craved seeing the reality of a family (and a woman!) negatively impacted by the economy doing their best to make ends meet. While vampire and zombie TV creates a nice little escape (and interesting metaphors, for sure) from the bullshit most of the country is experiencing right now, I wanted to watch a show that didn’t merely offer escape but reminded the world that these families exist; this is a serious crisis; and we are not going to ignore it.

And so that’s how my love affair with Roseanne and the Conner family re-began.

|

| Darlene Conner |

Most of the time I played it in the background while I ate dinner or washed the dishes, because, for the many reasons I stated above, I found the hilari-dysfunction of the Conner family comforting. Then one night while I surfed the net, barely paying attention to the show, I heard Roseanne’s sister Jackie say, “Do you think you might have an abortion?” I honestly don’t think I’ll ever forget that moment—I looked up from my computer in shock, like, Did someone just fucking say the word “abortion” on TV?

Many writers gave wonderful examples during Reproduction & Abortion Week of how abortion—both the portrayal of abortion and the word itself (see Knocked Up)—have been all but avoided in recent films and television, although current shows like Friday Night Lights and Grey’s Anatomy certainly offer hope. But Roseanne’s two-episode arc about a woman’s right to choose—which aired in 1994 (almost 20 years ago)—discussed abortion so openly and unapologetically, especially in its acknowledgment of men’s role in the decision-making process (hint: it’s the woman’s decision, always), that it honestly floored me.

|

| Roseanne taking a pregnancy test |

The premise goes like this: Roseanne and Dan want to have another baby, and she becomes pregnant. They find out from a nurse after Roseanne’s amniocentesis (to determine the sex of the baby), that there might be complications in her pregnancy. They can’t get in touch with the doctor to find out the exact problems (because it’s Thanksgiving!), and that sets up the catalyst for a long, two-episode discussion about whether Roseanne—depending on the extent of the complications—would want to have the baby or have an abortion. Roseanne feels as though Dan is pushing her to have an abortion, whereas she’s leaning toward having the baby, regardless of the circumstances. The two episodes illustrate the problems that arise when several characters weigh-in on Roseanne’s decision.

One of the first conversations about Roseanne’s pregnancy happens between Roseanne and her sister Jackie:

Roseanne [talking about her husband Dan]: All’s he thinks about is himself, you know. He’s worried that a sick baby might be an inconvenience to him, so he’s trying to hint around that I should have an abortion.

Jackie: Oh, I’m sure he knows it’s your decision. I mean, he must respect your right to choose.

Roseanne: Yeah, as long as I choose to agree with him.

A few minutes later, Dan enters the kitchen, interrupting their conversation, and Roseanne asks him to start painting the baby’s crib. He suggests that they wait to paint the crib until they hear back from the doctor. Roseanne gets angry, and after he leaves the kitchen (presumably to begin painting the crib), Jackie and Roseanne pick up where they left off:

Jackie: You’re right, you know, he was pushing you. I thought Dan was better than that.

Roseanne: Why? He’s a man. You know, this is the only area in the world [circles stomach with her hand] that they can’t control, and it drives them crazy ’cause it doesn’t come with a remote. [audience laughter]

I particularly like this interaction between Roseanne and Jackie because it shows two women talking about a woman’s right to choose (using that exact language!) as if it’s obvious that it’s her right. And neither of them lets Dan off the hook for putting pressure on Roseanne, however subtle it may be, to have an abortion. We find out later though, during a discussion at a bar between Fred (Jackie’s husband) and Dan, that Dan does seem to understand that the decision about the baby ultimately resides with Roseanne:

Fred: I just don’t think you’d be a terrible person if you demanded some control over what Roseanne’s gonna do … Look, having a kid, it’s half yours, this is a 50/50 proposition.

Dan: Yeah, when it finally comes out. You gotta admit, Fred, this is different.

I like this interaction between Dan and Fred, too, because it illustrates a larger cultural problem in the conversation surrounding abortion and a woman’s right to choose: where do fathers fit into the equation? Even though Fred thinks men have the right to “demand some control” (yikes, current War on Women!) over what a woman does with her body, Dan, regardless of his personal feelings about abortion, understands that he—and men—should not exercise control over women’s bodies.

|

| DJ Conner |

The most compelling conversation about Roseanne’s right to choose surprisingly occurs between Roseanne and DJ, her twelve-year-old son. After hearing so much yelling and whispering between his parents over the course of several days, DJ becomes concerned that his mom might be sick. Roseanne decides to tell DJ the truth about the situation.

Roseanne: Okay, I’m gonna tell you the truth because you’re not a little kid anymore. I’m okay, but, um, there’s a chance that something’s wrong with the baby.

DJ: Oh.

Roseanne: Yeah. So I have to, uh, make a decision whether to have it or not.

DJ: You mean you might have an abortion?

Roseanne: Uhh, yeah, that. Maybe. I don’t know. It’s just a very, very complicated decision, DJ.

DJ: Why?

Roseanne: Because I have wanted to have a baby for a long time.

DJ: Well if you decide not to have the baby, when you come back from the hospital, we can take care of you.

Roseanne: Hey, I know you’re gonna be a man someday, but see, you cannot do this.

DJ: Do what?

Roseanne: No man has any right to tell any woman what she should do in a situation like this.

DJ: I’m not, I’m just saying that if you do have the baby and it’s sick, we can take care of the baby too.

Roseanne: So you mean you’re saying like, uh, saying what—that you would support any decision I make?

DJ: Yeah.

Roseanne: Oh, well [audience laughter] … thanks. Thanks a lot, DJ. It really makes me feel better that you can handle the truth.

This scene in particular moved me. DJ—a young boy who hasn’t yet been negatively influenced by the Mass Cultural Ownership of Women’s Bodies—reserves all judgment regarding his mother’s decision about the baby. He says the word “abortion” in a matter-of-fact way, as if he’s asking his mother what time it is. He offers to support her, no matter what she decides, and he makes it clear that he understands the decision is only hers. This scene also represents the first time Roseanne says outright, “No man has any right to tell any woman what she should do in a situation like this.” Admittedly, DJ can’t fully comprehend the complexity of such a decision, or how life might change for the entire family if a new baby needed special attention; however, it never occurs to him to try and influence Roseanne’s choice. Again, I attribute that to DJ’s innocence, specifically surrounding his ignorance of the dominant cultural narratives. (See the recent all-male birth control panel and the mostly male-dominated GOP’s attack on Planned Parenthood and, you know, women’s healthcare in general.)

Roseanne and Dan eventually find out that their baby is healthy. Roseanne decides to give birth to her. But that isn’t the point of this episode arc at all. The discussion of choice, especially when 1 in 3 women chooses abortion, matters. The media, including television and film, needs to accurately reflect the realities of women’s lives because it matters. The more we see what women truly struggle with, depicted in an honest way, the more we can erase the stigmas associated with abortion and women’s reproductive rights in general. These episodes aired 25 years ago, and—amid the absolutely embarrassing and unacceptable War on Women—puts the current (undeniable) feminist backlash in perspective.