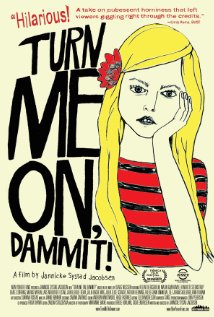

The 2011 Norwegian film, Turn Me On, Dammit! is, in a word, excellent. In the world of about a thousand American Pie films and cliched male teen sex comedies that usually revolve around bathroom jokes and well-endowed foreign exchange students, Turn Me On, Dammit! follows a more female centered theme that is as insightful as it is witty.

The star of Turn Me On, Dammit! is Helene Bergsholm who plays Alma, a 15-year-old girl who lives in a small town in Norway and is just realizing the amazing, albeit embarrassing, world of teenage hormones and sex. One night at a party, Alma’s crush, a boy at her school named Artur, exposes himself to her (or as the film’s refrain goes, “pokes her with his dick”) but when Alma excitedly tells her friends about the encounter, a jealous girl refuses to believe the story and spreads it around that Alma is a liar. Artur as well, embarrassed that he’s been confronted with the situation, denies that it ever happened, sending young Alma into the lonely world of high school drama.

The film’s writer and director, Jannicke Systad Jacobsen, fills the film with an excellent commentary on the fact that often, men are believed over women in situations of sexual harassment and assault. Now, while Artur and Alma’s situation is slightly different since it was youthful, consensual experimentation and not assault, the point is still there: women accuse, men deny. Jacobson however doesn’t strike an agressive tone with this theme, rather she couches the exposition of it in terms of courage and cowardice. Artur is a young coward too scared to admit the truth and instead just watches as Alma is increasingly shunned and ostracized from her friends.

|

| Malin Bjorhovde, Helene Bergsholm, Beate Stofring in Turn Me On, Dammit! |

This theme is one that avoids blame and victimization, focusing instead on the human propensity to make stupid (and even cruel or damaging) mistakes and either be a coward about it, or face the consequences. A gender-relevant argument that doesn’t feel aggressive, giving the film a wide appeal to audiences.

While there is some slight “slut-shaming” that occurs in the film (Alma’s new nickname, “Dick Alma” is called after her by even small children), there is more of a focus on how Alma’s sexual activities lead the people of the town, as well as her mother, to think that she must be crazy or abnormal in some way. It’s a familiar sort of idea in the teen sex comedy, the raging sexual hormones of youth leading to a certifiably insane son or daughter whose activities seem to be those of pervert. Take for example the famous scene in American Pie when Jim decides to have sex with an apple pie because he believes it will simulate how sex actually feels; naturally, that is the exact moment that his father walks in the room.

The scene in American Pie, however, is so extreme that it could never be real, a problem that Jacobsen doesn’t have. Alma’s scene’s of “sexual craziness” are awkward and embarrassing to be sure, but never outside the realm of possibility, grounding her characters in in a more realistic comedy. Because of this, Alma is ultimately able to attain something that most characters in a teen sex comedy never can: self-respect. Turn Me On, Dammit! is at its core a film about growing up and gaining confidence in ourselves, a true coming-of-age story where Alma reaches self-acceptance and Alma’s mother is able to do the same for her daughter.

So many parental-child relationships are sacrificed in teen movies, parents becoming bumbling idiots whose outdated slang and terrible educational sexual analogies feed into cliched humor. It’s a shame that’s the case since Alma’s mother’s quiet confusion and occasional fear of her daughters healthy curiosity in sexuality lends a lot of subtle humor to the film. Alma’s mother feels her daughter must be abnormal in some way and so all she begins to see is the apparent erratic and embarrassing behavior of her daughter, not realizing the social exclusion her daughter is experiencing. Alma as well doesn’t see her mother’s loneliness and attraction to her boss; it’s a moment of selfishness for each character in their unwillingness to empathize with the other.

While the mother and daughter relationship is a strong plot point for the film, my favorite exposition is the very female-centered, sex-positive demonstration of female fantasy. So often visual sexual fantasy in films remains squarely in the center of the male gaze: women in bikinis washing cars, licking ice cream cones, and rising silkily out of a swimming pool come to mind. Alma not only has a very sweet, male phone sex worker friend (who is willing to also just listen to the problems of a young girl, albeit his solution to those problems are “booze”), but also fantasizes about her crush in both the sweet and the sexy, her boss (hilarity with a bike helmet and “I’m bringing sexy back”), and most notably, a fantasy about her female friend. Female fantasy is often kept in the overly dramatic (when it is portrayed at all) and rarely are same-sex fantasies expressed from a straight woman, a fact I find unfortunate since it’s been scientifically proven that most straight women are actually more sexually flexible in their arousal than men.

I suppose that my analysis has made the film sound like the only thing that is ever discussed is sex; this is however, not the case–obviously the issue of first love is important, drugs make an appearance, as does a surprising commentary on the American legal system. One of the main characters, Alma’s friend Saralou, is a social activist concerned with the plight of American prisoners on death row, she in fact writes letters to American prisoners, often discussing the local high school drama with various offenders.

The strengths (as well the flaws) of female friendships are portrayed in the film, giving a varied look at the silly and serious side of young people. Instead of a world bound by stereotype and cheap laughs, Jacobsen has created a rich and deeply human world filled with genuine characters and issues. And sex.

Rachel Redfern has an MA in English literature, where she conducted research on modern American literature and film and it’s intersection, however she spends most of her time watching HBO shows, traveling, and blogging and reading about feminism.