Written by Andé Morgan.

Some topics to avoid at a holiday dinner (aside from the fact that Columbus was an awful, awful man or that Jesus probably wasn’t born on December 25): politics, religion, and, if several generations of feminists are sitting around your table, sex work. I can’t bridge that chasm here, but I can tell you that I support the recognition of the human rights of both sex workers and transgender people (big of me, I know). Consequently, I appreciate stories that portray sex workers and transgender people as real people.

Unfortunately, I wince reflexively whenever I hear about a transgender character in a new movie or TV show. The notable exception of Laverne Cox in Orange is the New Black not withstanding, transfolk on screen are usually one-dimensional, and typically function to fill in a story or to be a catalyst for another (cis)character’s development. We’re familiar with the transgender character as a caricature: the “tranny” who is deceptive, immoral, dirty, ugly, and undesirable. These characters don’t develop. They’re either cheap punchlines, or they provide an opportunity for the main (cis)character to develop tolerance or sensitivity.

While many transfolk have never been sex workers, many others have, either by their own volition or because of systemic transphobia and inadequate employment protections. In film, transwomen are often portrayed as sex workers. The typical depictions of transgender people parallel the typical depiction of sex workers as uneducated, diseased, abused, addicted, unloved, and overly sexual. The sex worker also exists as a joke, a mistake, a “dead hooker,” a ruiner of marriages, or as a weak person in need of saving. Or, if we’re watching lighter fare, as a happy “hooker with a heart of gold.” These tropes fail to depict sex workers and transgender people as real people. This trend is disturbing because entertainment shapes public opinion, which in turn shapes public policy.

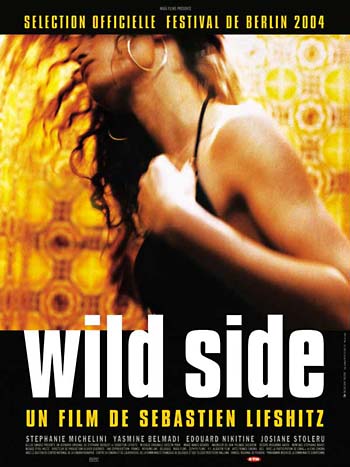

Wild Side was released in Germany in 2004 (distributed by Wellspring, not rated) and bucks that trend. Directed by Sébastien Lifshitz, the film follows transgender sex worker Stéphanie (played Stéphanie Michelini, who is transgender in real life, thank you very much Jared Leto) upon her return to her rural childhood home to care for her ill mother. Stéphanie is joined by her roommates and lovers Mikhail (Edouard Nikitine), and Djamel (Yasmine Belmadi). Like much of Lifshitz’ previous work, Wild Side explores sexuality and emotional intimacy. Thankfully, Stéphanie’s gender identity or Mikhail and Djamel’s bisexuality are not the sole focus, but rather appropriately important facets of their characters.

The drama takes its name from the Lou Reed song. The film opens with another song, “Fell in Love with a Dead Boy,” sung by an androgyne (Antony Hegarty) to a roomful of transgender sex workers. As a song lyric asks the question “are you a boy or a girl,” the scene fades on a tear rolling down Stéphanie’s face. Next, we see a slow body shot of Stéphanie’s nude, reclining form, including her breasts, her pubic hair, and her penis.

Backstories are told through flashbacks. We learn that Stéphanie grew up in rural northern France as Pierre, the only son of a farming couple and sibling to Caroline. It’s implied that Stéphanie was bullied in school for her perceived effeminacy, and that her father and sister were killed when Stéphanie was young. Her relationship with her mother, Liliane (Josiane Stoléru), is strained. Stéphanie now lives in Paris where she gets by as a sex worker and lives in a polyamorous relationship with Mikhail, an undocumented Russian army deserter (and former client–sort of), and Djamel, who is also a sex worker.

Out of the blue, Stéphanie receives a call: her mother is severely ill and needs a caretaker at Stéphanie’s childhood home, a lonely farmhouse. Stéphanie and Mikhail go immediately, and are soon followed by Djamel. Here, the character development truly takes off. I was stunned by Lifshitz’ ability to use his actors to display the depth of the humanity of the characters. Stéphanie, Mikhail, and Djamel are not defined by what they do to survive. Rather, they are complicated, and want the same love, connectedness, and warmth that we all want. With beautiful subtlety, Stéphanie is able to express the alternating awkward hope, disappointment, and cautious optimism that characterizes family relations for many transgender people. Stoléru is also magnificent, conveying masterfully with facial gestures and glances the internal conflict between her desire to comfort and be with her child, and her reluctance to release the Pierre-son construct she still clings to.

While we see fairly graphic depictions of urgent sex in the scenes that establish Stéphanie and Djamel’s vocations, the scenes of lovemaking among the trio are gorgeously tender. This same softness and sense of attachment is displayed outside of the bedroom as well: rolling together down a countryside hill; Mikhail teaching Djamel how to box; and Djamel teaching Mikhail to speak French. Stéphanie’s first post-transition visit to her first love, Nicolas (Christophe Sermet), filled me with happiness; they talk about travel, having children, and other mundane things. While initially surprised, Nicolas clearly accepts Stephanie for who she is, is happy to see her, and that’s it.

As is life, endings are both happy and sad, and some things are never resolved. There is no miraculous recovery. While they make a peace of a sort, Stéphanie and Liliane don’t develop the carefree, demonstrative, unconflicted relationship that they both desperately want. The trio returns to Paris, in love, but facing an uncertain future.

Wild Side is a great film. The score, photography, and direction combine with the earnest performances of the neophyte actors to produce a film with depth, consistent motifs and evocative imagery. More important than that, the film is one of few I know that authentically and sympathetically portrays not only transgender people, but also bisexual people, people in polyamorous relationships, and sex workers. I highly recommend it, and don’t let the subject matter or the somewhat somber pacing fool you–there is a strong thread of joy in this film.

Andé Morgan lives in Tucson, Arizona, where they write about culture, race, politics, and LGBTQ issues. Follow them @andemorgan.

Must see it!

Have you seen “Cheila: una casa pa maíta” (a house for mom)? It’s a good venezuelan movie with a trans character, played by a transgender actress. The story revolves around her and her family.

Here it was quite a success considering the difficult subject it touches. You might like it.