This guest post by Shay Revolver appears as part of our theme week on Representations of Sex Workers.

The year was 1993. For the most part the 90s were starting out to be a good year for non-traditional female characters in film. Having sat through Pretty Woman on video at a sleepover once, I found myself not impressed. I got that Julia Roberts’s character was a sex worker, but I didn’t get the whole appeal of a character whose sole purpose was to be a damsel in distress. I was always more of a fan of stories where a woman could handle herself and it was cool if a guy came along to help but, for the most part, she had it covered. True Romance was one of those films and the first time I saw it, I loved it so much that I watched it in the theater three times that day, only breaking for meals and bathroom breaks.

On its surface, True Romance comes off as yet another story about a guy who saves a girl from a horrible existence as a sex worker and he protects her forever and they live happily together forever and ever, the end. But, if you’ve ever seen it, you know that this is not the case. Alabama Whitman is a hero in her own right. She’s never apologetic about her sex life or her choices; they are what they are and she’s OK with it. In fact, had she not met and fallen in love with Clarence, her short career as a sex worker might have continued. After their met, via set-up, and fall in love, it was Clarence’s idea to save her. Alabama was content to just stay with him, or run away, and continue living her life as she wished. Clarence, on the other hand, feeling emasculated by the idea that her pimp Drexl still existed and had somehow sullied his wife’s virtue, goes on the offensive and decides to show how manly he is by being a valiant knight, retrieving her belongings and saving her from her past. He reads her logical concern for his safety as yet another challenge of his manhood and sets off to right the wrong.

While Clarence goes off to play night in shining armor, which in this film is code for getting his tail kicked by Drexl and his body guard, Alabama sits at their apartment watching TV. She doesn’t actually think that Clarence would be stupid enough to actually go and confront Drexl. But he does, and after a stroke of luck with a misfired gun, Clarence returns to present his lady love with news of her former pimp’s demise and her things. Alabama finds this all super romantic because he fought for her. But not in the Pretty Woman, or traditional damsel in distress film, way where she falls into his arms and thanks him for taking her away to a better life because she never could have done it in her own kind of way. She thanks him because it was a sweet gesture and she really didn’t expect him to do it, or survive if he had, and she was happy that he cared enough to try. Alabama, being the smart, capable, woman that she was, would have been totally OK with leaving all of her stuff at Drexl’s and continuing her life with Clarence, never looking back. It wasn’t the “rescue” that made it romantic for her, it was the caring. Granted, Clarence’s motives were equal parts love and a male sense of ownership, but there was still something endearing about it.

There was also something endearing about the fact that you knew that this movie was about to go all kinds of crazy and with Alabama being the only female in a film full of men, you knew in that moment that she was going to be OK and would totally be able to handle herself. From the very beginning nothing about Alabama’s character said damsel in distress. Even when she was crying about being in love on the roof, that came off as genuine emotion and guilt for starting out on a lie. She was a real person and she was about to go through some real things and you felt for her. You rooted for her and above all else you wanted her to win.

The rest of the film follows Clarence and Alabama on a cross country trek to LA to unload the drugs that they discovered in Alabama’s suitcase. Clarence has no idea what he’s doing and there is something wonderful about watching Alabama stand by her man while slowly guiding him into making decisions that are better than the ones that he comes up with on his own. He listens to her suggestions and leans on her, just as much as she leans on him. They act like pure equals. Despite Alabama’s past he never treats her like anything other than a human being. He also doesn’t allow anyone else to. There is something nice about the way the film doesn’t paint broad stroke generalizations of women who choose to be in the sex industry. Her job choice wasn’t a scarlet letter that followed her. Outside of Clarence’s initial must-save-my-woman reaction at the beginning that spawned his initial jump to action, the fact that she used to be a sex worker wasn’t really brought up. She didn’t get the usual movie treatment of women who didn’t color in the lines, or who enjoyed sex, or who needed redemption. She existed and she was OK. She wasn’t forced to feel ashamed or bad about her choices. There wasn’t the typical punishment for her “actions” of being a sexual being, or getting paid for it. She was allowed as a character to grow outside of that mold.

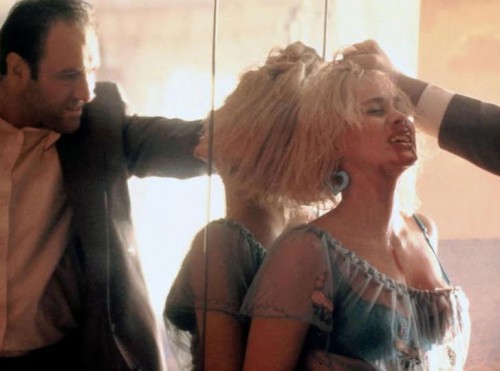

Throughout the film, Alabama proves herself stronger, and often smarter, than most of the males on screen. This strength and her smarts, combined with her survival instincts, drive the film. Watching her fight her way out of her hotel room, taking down James Gandolfini’s Virgil in pure gladiator style, was beautiful. She showed no fear, no hesitation, just power. And not the brute force, masculine power that Virgil displayed as he tossed her about but mental power. She realized that physically she was outmatched and used her brain. She was able to overpower him and eventually defeat him using her mental advantage. She didn’t wait it out for Clarence or another man to show up, which I’m sure most of the audience was expecting to happen after the brutal beating she received; she defeated him on her own. To this day, that scene is one of my favorite fight scenes in a film. Half of the audience expecting Clarence to barge in at the last moment, the other half hoping she would finish him off on her own and no one being disappointed with the outcome. That scene cemented Alabama Whitman as a hero, not just another pretty face in an iconic film, or a damsel in distress. After delivering that death blow she proved what anyone watching the film had known all along: she was a force to be reckoned with.

When Clarence finally does return to whisk her away to the drug deal so that they can put this gruesome past behind them and start like anew together in Mexico; she’s battered and bruised, but still OK. She sits there during the doomed drug deal, wearing her bruises like a badge of honor and still managing to show just enough feminine charm to keep things moving along while simultaneous giving off a “don’t mess with me” vibe. It was brilliant and beautiful. She retained her wits and strength throughout the downfall of the deal when everything crumbled around her and Clarence emerges from his chat with Elvis and gets shot in the eye amidst a massive shoot out. Alabama then saves the day again as she not only grabs the money but manages to drag an equally bloody and bruised Clarence out of the hotel room, through the lobby and on to safety.

In the on-screen version, Alabama and Clarence escape together and are seen frolicking on a beach in Mexico with their son. Clarence is missing an eye from the shoot out and you can see a happily ever after in their future. You’re very happy that they made it as a couple, but you’re even happier that Alabama got the life she wanted and you can’t help but cheer. Owning the special edition version of the DVD, I have seen the ending that Quentin Tarantino wrote. Tony Scott famously shot it and didn’t use it because he didn’t want to split up the couple; he wanted them to both win. In the Tarantino ending, Alabama drives off on her own with the money and heads on to her new life. Clarence is dead and she’s upset by his stupidity in not listening to her in the first place. It was a cold ending, but you are still happy knowing that she made it, she’s OK, and she will continue to be OK because she’s proven herself nothing close to a damsel in distress. She’s strong, smart, and capable. Most people who have seen both endings have their favorite. I will go on record and say that either way is fine with me because Alabama is a character that not only resonated with me but has also stuck with me since I first saw the film. She showed that even in a “guy” film, filled with testosterone, violence, and blood that the only woman on screen doesn’t have to be scenery, a distraction, a hindrance or some”thing” that needs protecting. She can hold her own with the guys and be a true equal in the story and on screen. We no longer had to be seen as victims or damsels in distress; we could be heroes too.

Shay Revolver is a vegan, feminist, cinephile, insomniac, recovering NYU student and former roller derby player currently working as a New York-based microcinema filmmaker, web series creator and writer. She’s obsessed with most books, especially the Pop Culture and Philosophy series and loves movies and TV shows from low brow to high class. As long as the image is moving she’s all in and believes that everything is worth a watch. She still believes that movies make the best bedtime stories because books are a daytime activity to rev up your engine and once you flip that first page, you have to keep going until you finish it and that is beautiful in its own right. She enjoys talking about the feminist perspective in comic book and gaming culture and the lack of gender equality in mainstream cinema and television productions. Twitter: @socialslumber13.

2 thoughts on “‘True Romance’ or How Alabama Whitman Started the Fall of Damsels in Distress”

Comments are closed.