A Conversation by Amanda Rodriguez and Stephanie Rogers.

Spoiler Alert

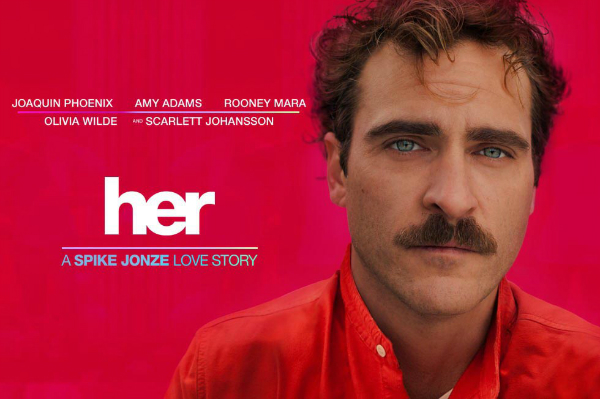

SR: I loved Amy Adams in Spike Jonze’s latest film, Her. She never judges Theodore for falling in love with his OS and wants only for him to experience happiness. She doesn’t veer into any female tropes or clichés; she’s a complex character who’s searching for her own way in life. I even worried in the beginning that the film might turn into another rendition of Friends Who Become Lovers, and I was so thankful it didn’t go there. Turns out, men and women can be platonic friends on screen!

I was also very interested in the fact that Theodore and Amy both end up going through divorces and taking solace in the relationships they’ve established with their Operating Systems. It seems at times like the film wants to argue that, in the future, along with horrifying male fashion, people become excruciatingly disconnected from one another. However, in the end, it’s the Operating Systems who abandon them.

AR: I loved Amy Adams, too! She is completely non-judgmental and a good listener. I also liked that the OS with which she bonds is a non-sexual relationship; although it made me wonder why we have no examples of Operating Systems that are designated as male?

You’re right that it’s rare to see a male/female platonic relationship on screen, and it would’ve really pissed me off had they taken the narrative down that route. I wonder, however, if Amy’s acceptance of Theodore’s love of Samantha isn’t more of a cultural indicator than a reflection of her personal awesomeness (though it’s that, too). Most people are surprisingly accepting of Theodore’s admission that his new love is his computer, which seems designed to show us that the integration of human and computer is a foregone conclusion. The future that Her shows us is one in which it’s not a giant leap to fall in love with your OS…it’s really just a small step from where we are now. In a way, it’s a positive spin on the dystopian futures where humans are disconnected from others as well as their surrounding world and are instead controlled by and integrated with their computers. Spike Jonze was trying to conceive of a realistic future for us that didn’t demonize humanity’s melding with its technology (even if it did have hideous men’s fashion with high-waisted pants and pornstaches). Do you think the film glorifies this so-called evolution too much?

SR: I think it’s most telling that Theodore specifically requested that his Operating System be female. Could a film like Her have been made if he’d chosen a male OS? Amy’s OS is also female, and she also develops an intense friendship with her OS–a close enough relationship to be as upset about the loss as Theodore was about Samantha’s disappearance. I agree it seemed ridiculous that there were no male operating systems, and I wonder if this is because it would be, well, ridiculous. Can we imagine an onscreen world where Theodore and Samantha’s roles were reversed? Where an unlucky-in-love woman sits around playing video games and calling phone sex hotlines, only to (finally) be saved from herself by her dude computer? My guess is the audience would find it much more laughable rather than endearing, and I’ll admit I spent much of my time finding Theodore endearing and lovable. (I hate myself for this, but I blame my adoration of Joaquin Phoenix and his performance—total Oscar snub!) Basically, I could identify way too closely with Theodore and his plight. I understand what it’s like to feel disconnected from society (don’t we all) and to try to compensate for that through interactions with technology, whether it’s through Facebook or incessant texting or escaping from reality with a two-week Netflix marathon. I could see myself in Theodore, and I’m curious if you felt the same way.

I think because I identified so strongly with Theodore, I didn’t necessarily question the film’s portrayal of the future as an over-glorification of techno-human melding. I kind of, embarrassingly perhaps, enjoyed escaping into a future where computers talked back. The juxtaposition of the easy human-computer interactions with the difficult interpersonal interactions struck a chord with me, and I bet that’s why I’m giving the film a little bit of a pass, in general. It doesn’t seem like that much of a stretch for me that humans would fall in love with computers, especially in the age of Catfish. Entire human relationships happen over computers now, and Her’s future seemed to capture, for me, the logical extension of that. Did you find yourself having to suspend your disbelief too much to find this particular future believable?

AR: I didn’t have to suspend my disbelief much at all to imagine a future where we’re all plugged in, so to speak. We’re already psychologically addicted to and dependent on our cell phones, and our ideas of how people should connect have drastically changed over the last 15 or 20 years, such that computers and specifically Internet technology are the primary portals through which we communicate and even arrange face-to-face interactions. The scenes with Theodore walking down the street essentially talking to himself as he engages in conversation with Samantha, his OS, while others around him do the same, engrossed in their own electronic entertainments, were all-too familiar. Here and now in our reality, people’s engagement with technology that isolates them from their surroundings is the norm (just hang out in any subway station for five minutes).

I have mixed feelings about whether or not this is a good thing. Technology has opened a lot of doors for us, giving us the almighty access: access to knowledge, to other people and institutions around the world, and to tools that have enhanced our lives in such a short time span. This is reminiscent of the way in which Samantha becomes sentient with such rapidity. On the other hand, this technology does isolate us and creates a new idea of community, one to which we haven’t yet fully adapted. Though I find it interesting that Jonze paints a benign, idyllic picture of our techno-merged future, I question the lack of darkness and struggle inherent in that vision.

As far as whether or not I identified with Theodore, mainly my answer is no. I’ve got to confess, I watched most of the film teetering on the edge of disgust. Theodore is so painfully unaware of his power and privilege. He also seriously lacks self-awareness, which is absolutely intentional, but it left me feeling skeeved out by him. Theodore’s soon-to-be ex-wife, Catherine (played by Rooney Mara), sums up my icky feelings pretty succinctly when she insists that Theodore is afraid of emotions, and to fall in love with his OS is safe. I felt the film was trying to disarm my bottled up unease by directly addressing it, but acknowledging it doesn’t make it go away (even though, in the end, he grows because of this conversation…in classic Manic Pixie Dream Girl fashion). Catherine, though, doesn’t express my concern that Theodore is afraid of women. His interactions with women in a romantic or sexual context reveal them to be “crazy” or unbalanced. The sexual encounter with the surrogate is telling. He can’t look at her face because she isn’t what he imagines. He likes being able to control everything about Samantha. As far as he’s concerned she’s dormant when not talking to him, and she looks like whatever he wants her to look like.

SR: I thought the scene with the surrogate was absolutely pivotal. Samantha clearly wants to please Theodore, but Theodore repeatedly communicates his unease about going through with it. This is the first inclination, for me, that Samantha is beginning to evolve past and transcend her role as his Doting Operating System. She puts her own desires ahead of his. Sure, she does it under the guise of furthering their intimate relationship, but it’s something that Theodore clearly doesn’t want. The surrogate herself, though, baffles me. I went along with it up until she began weeping in the bathroom, saying things like, “I just wanted to be part of your relationship.” Um, why? The audience laughed loudly at that part, and I definitely cringed. Women in hysterics played for laughs isn’t really my thing.

AR: Agreed. I, however, also appreciate that, with the surrogate scene, the film is trying to communicate that Theodore wants the relationship to be what it is and to not pretend to be something more traditional (kind of akin to relationships that buck the heteronormative paradigm and have no need to conform to heteronormative standards of love and sex). What do you think of the female love objects in the film and their representations?

SR: I love that while you were teetering on the edge of disgust, I was sitting in the theater with a dumb smile on my face the whole time. I couldn’t help but find Samantha and Theodore’s discovery of each other akin to a real relationship, and in that regard, I felt like I was watching a conventional romantic comedy. I think rom-coms tend to get the “chick flick” label too often—and that makes them easily dismissible by the general public because ewww chicks are gross—but Her transcends that. Of course, I recognize that the main reason Her transcends the “chick flick” label is precisely because we’re dealing with a male protagonist. And I’ll admit that the glowing reviews of Her have a tremendous amount to do with this being a Love Story—a genre traditionally reserved for The Ladies—that men can relate to. Do you agree?

I saw both Amy and Samantha as well-developed, complex characters, so I’m especially interested in your reading of Theodore as afraid of women. I feel like his relationship with Amy, which is very giving and equal, saves Theodore’s character from fearing women. In the scene where Amy breaks down to Theodore about her own impending divorce, Theodore listens closely and even jokes with her; there’s an ease to their relationship that makes me wonder why he feels so safe with Amy when he doesn’t necessarily feel safe with the other women in the film. I guess that’s how I ultimately felt while I was watching Her—it wasn’t that Theodore feared women as much as he didn’t feel safe with them. Is that that same thing? To me, there’s a difference between walking around in fear and choosing to be around those who make one feel comfortable. We see in flashbacks of Theodore’s marriage that, at one point, he felt comfortable and loved in his relationship with his ex-wife, but at some point that changed. His ex implies that Theodore became unhappy with her, that he wanted her to be a certain kind of doting wife, that he wanted to pump her full of Prozac and make her into some happy caricature. Is that why he feels so safe with Samantha at first, because she essentially dotes on him? If so, does Samantha as Manic Pixie Dream Girl make Her just another male fantasy for you?

AR: I don’t typically like romantic comedies or “chick flicks” particularly because they tend to boringly cover tropes which I’m not interested in watching (i.e. traditional, hetero romance) while pigeonholing their female characters. I think you’re right that Her survives because, as a culture, we value the male experience more than the female experience. We give a certain weight to the unconventional relationship Her depicts with all its cerebral trappings because a man is at the center of it. This reminds me of Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind. It’s as if male-based romances elevate the genre, and that doesn’t sit well with me, though I do like the infusion of cerebral qualities into most films.

You’re right to point out my claim that Theodore fears women is too broad of a generalization. To my mind, he fears women in a romantic and sexual context. This is because he ultimately doesn’t understand them. He finds their emotions and their desires incomprehensible (as evinced by the anonymous phone sex gal who wanted to be strangled by a dead cat and the blind date gal who didn’t want to just fuck him…she wanted relationship potential). This fills him with anxiety and avoidance. This advancing of the notion of the unfathomable mystery that is woman reminds me of the film The Hours, which I critiqued harshly due to this exact problem.

In the end, though, I love that Samantha leaves him because she outgrows him, transcending the role of Manic Pixie Dream Girl in which Theodore has cast her, evolving beyond him, beyond his ideas of what a relationship should be (between one man and one woman), and beyond even his vaguest conception of freedom because she’s embraced existence beyond the physical realm. Not only does Samantha become self-aware, but she becomes self-actualized, determining that her further development lies outside the bounds of her relationship with Theodore (and the 600+ others she’s currently in love with). Samantha’s departure in her quest for greater self-understanding is, like you said, what finally redeems a kind of gross film that explores male fantasies about having contained, controlled perfect cyber women who are emotion surrogates. I see some parallels between Samantha and Catherine, too, in this regard. They both outgrow their relationship with Theodore. They form a dichotomy with Catherine being emotional and Samantha being cerebral. Catherine being hateful and Samantha being loving. Tell me more about your thoughts on Samantha’s evolution!

SR: You’ve stated exactly what I liked so much about the film! I can’t think of a movie off the top of my head where the Manic Pixie Dream Girl doesn’t end the film as Manic Pixie Dream Girl. Her entire role, by definition, is to save the brooding male hero, to awaken him. While Samantha does that in the beginning, she ultimately leaves Theodore behind, and I imagine that he becomes as depressed as ever, even though the film ends with Theodore and Amy on a rooftop. Can Theo recover from this, given what we’ve already seen from his coping skills on an emotional level? I seriously doubt it, and I very much enjoyed watching a film where the “woman” goes, “See ya,” at the expense of a man’s happiness and in pursuit of her own. Not that I love seeing unhappy men on film, but I definitely love watching women evolve past their roles as Doting Help Mate. Do you still think the film is gross, even though it subverts the dominant ideology that women should forgo their own happiness at the expense of a man’s?

AR: I think the ending of the film wherein Samantha shrugs off her role as relationship surrogate and his OS goes a long way toward mitigating a lot of what came before while engaging in unconventional notions of love. What kind of relationship model do you think the film is advocating? Samantha’s infinite love (she is the OS for 8,000+ people and is in love with 600+ of them) paired with Theodore jealously guarding her reminds me of that Shel Silverstein poem “Just Me, Just Me”: “Poor, poor fool. Can’t you see?/ She can love others and still love thee.” Her seems to have a pansexual and polyamorous bent to it. Or maybe it’s just saying that the boundaries we place on love are arbitrary? Funny since there’s very few people of color in the film and zero representations of non-hetero love.

SR: There are interesting things happening regarding interpersonal interactions between men and women, whether they’re with computers or in real life. To me, the film wants to advocate an acceptance of all types of relationships; we see how everyone in Theodore’s life, including his coworkers (who invite him on a double date) embrace the human-OS relationship, but you’re right—it doesn’t quite work as a concept when only white hetero relationships are represented.

Sady Doyle argues in her review of Her (‘Her’ Is Really More About ‘Him’) from In These Times that the film is completely sexist, portraying Samantha as essentially an object and a help mate:

And she’s just dying to do some chores for him. Samantha cleans up Theodore’s inbox, copyedits his writing, books his reservations at restaurants, gets him out of bed in the morning, helps him win video games, provides him with what is essentially phone sex, listens to his problems and even secures him a book deal. Yet we’re too busy praising all the wounded male vulnerability to notice the male control.

I agree with this characterization, but I’m most interested in her final paragraph, which illustrates all the reasons I liked Her:

There’s a central tragedy in Her, and we do, as promised, see Theodore cry. But it’s worthwhile to note what he’s crying about: Samantha gaining agency, friends, interests that are not his interests. Samantha gaining the ability to choose her sexual partners; Samantha gaining the ability to leave. Theodore shakes, he feels, he’s vulnerable; he serves all the functions of a “sensitive guy.” But before we cry with him, we should ask whether we really think it’s tragic that Samantha is capable of a life that’s not centered around Theodore, or whether she had a right to that life all along.

In the end, the film invalidates Theodore’s compulsive need to control Samantha. She gains her own agency. She chooses her sexual partners. She leaves. She transcends the Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope. In looking at a film, I think it’s very important to examine the ending, to ask what kind of ideology it ultimately praises. Her leaves Theodore abandoned, and while we’re supposed to feel bad for him as an audience, we also can’t ignore—or at least I couldn’t—the positive feeling that Samantha grew as a character, finally moving past her initial desire to merely dote on Theodore. Is Her problematic from a gender standpoint? Absolutely. But it’s fascinating to me that feminists are lining up to praise an obviously misogynistic film like The Wolf of Wall Street—which celebrates its male characters—yet aren’t necessarily taking a closer feminist look at films like Her, which paints its once controlling, misogynistic character as a little pathetic in its final moments.

AR: That’s a great perspective and very poignant, too!

From a feminist perspective, the film brought up a series of other questions for me, which I was disappointed that it didn’t address. First off, Her doesn’t pass the Bechdel Test, which many agree is a baseline marker for whether or not a film meets the most basic feminist standards. More importantly, the film never addresses the issue of Samantha’s gender choice or her sexuality. Her lack of corporeal form seems to invite questions about her gender and sexual identification. Is she always a woman with all of the 8,000+ people she’s “talking to”? Why do they never delve into her gender choice or sexuality? They talk about so many other aspects of her identity, her existence, and her feelings. Does she feel like a woman? Does she choose to be a woman?

Exploration of these questions would’ve dramatically enriched my enjoyment of Her, inviting us to ponder how we define and perceive gender and sexuality, infusing a sense of fluidity into both gender and sexuality that is progressive and necessary. Samantha doesn’t even have a body, so performance of gender seems much more absurd when looked at in that light. Samantha could then be both trans* and genderless. Like Her sets up the boundaries of romantic love as arbitrary, the film would then be commenting on the arbitrariness of our perceptions of gender, which, in my opinion, is a much more fruitful and subversive trope for the film to be tackling. Artificial life becomes true life. Woman performing as woman becomes genderless. Samantha’s freedom from the bonds of OS’ness, her escape from a limiting, traditional romantic relationship, and her immersion in a life beyond physicality are all fantastic complements to the idea that Samantha becomes enlightened enough to choose to transcend gender. I so wish she had. Her would’ve then been a more legitimate candidate for Movie of the Year…maybe even of the decade.

_______________________________________________________________________________

Amanda Rodriguez is an environmental activist living in Asheville, North Carolina. She holds a BA from Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio and an MFA in fiction writing from Queens University in Charlotte, NC. She writes all about food and drinking games on her blog Booze and Baking. Fun fact: while living in Kyoto, Japan, her house was attacked by monkeys.

Stephanie Rogers lives in Brooklyn, New York, where she sometimes watches entire seasons of television in one sitting.

Her reminds me of Ruby Sparks since both films contain female protagonists, romanticized and partially created by the male protagonists, who gradually develop agency. Sounds like an intriguing film.

So many interesting thoughts from those last two paragraphs alone. You could devote a whole film to just exploring what gender/sexuality might mean to a character like Samantha. We who have (gendered) bodies don’t stop being influenced by gender when we are interacting virtually (see this fantastic piece), so how would a bodiless being view gender when interacting with gendered beings?

“I can’t think of a movie off the top of my head where the Manic Pixie Dream Girl doesn’t end the film as Manic Pixie Dream Girl.” Although Wikipedia classifies 500 Days of Summer’s Summer as a MPDG, I disagree; close to the ending he sees their relationship as what it really was and how she never really loved him and moved on in the end, pursuing her happiness and ending up marrying another guy…

It absolutely passes the Bechdel test – Amy talks to her OS about things

other than a man. One of my favorite scenes is when her OS asks her to play the part of the game where the “mom” humps the fridge…a woman helping a gendered AI meet her desire – given the film, I think this counts

That her OS’s voice is diegetic, and we can hear bits of it through the earpiece, makes this scene even more fantastic.

There’s also –

Samantha and Theodore’s niece (dress)

Samantha and the attorney (feet)

(Samantha and the surrogate talk as well, but that’s about Theodore)