|

| Movie poster for The Uninvited |

This is a guest post by Nadia Smith.

[contains spoilers]

When I told a horror-fan friend in his early twenties that I was writing about The Uninvited, he said he had seen it. This came as a surprise, since it’s mostly older viewers and film historians who are aware of it. It turned out that he thought I was referring to the recent Korean film The Uninvited: A Tale of Two Sisters, and not the classic haunted house movie that had audiences screaming in the 1940s and drew comparisons to Alfred Hitchcock’s Rebecca (1940).

The Uninvited (1944), directed by Lewis Allen and released by Paramount Pictures, is an adaptation of a popular Gothic novel by the Irish writer Dorothy Macardle (1889-1958), also a playwright, historian, journalist, and prominent feminist campaigner. It was adapted for the screen by the British writer Dodie Smith, best known for 101 Dalmatians. The Uninvited, which easily passes the Bechdel Test, features some sexist characterizations and a conventional ending, stemming from Macardle’s complex views on gender as well as the demands of commercial romantic fiction and film production. Nevertheless, the film opens itself up to alternative readings and valuations of the characters.

In the film, siblings Rick, played by Ray Milland, and Pamela Fitzgerald, played by Ruth Hussey (who might at first be mistaken for a married couple), learn that the old house in Cornwall they have just purchased is haunted by two ghosts, one warm and benevolent and one cold and dangerous, and investigate the mystery surrounding the house’s previous residents in an attempt to end the hauntings. Rick falls for the much younger Stella Meredith (Gail Russell), whose parents, artist Llewellyn and his wife Mary, had once lived in the house with Carmel, an artist’s model from Spain who had an affair with Llewellyn. The Merediths and Carmel died when Stella was a small child, Mary by falling off a nearby cliff, and the shy, repressed, immature Stella, who idolizes her late mother, lives an isolated existence in the village with Commander Beech (Donald Crisp), her stern, morbid maternal grandfather. The Commander has an unhealthy obsession with his daughter’s memory, and Stella is virtually imprisoned in the house as the Commander tries to mold her in Mary’s image. So far, so Gothic. Local informants, as well as Mary’s friend Miss Holloway (Cornelia Otis Skinner), praise Mary’s virtue and angelic beauty to the Fitzgeralds, and denounce Carmel’s depravity. Rick’s frustration grows as he worries that Stella’s intense emotional investment in her mother’s ghost will lead to a psychological breakdown and prevent her from ever caring for him.

The Fitzgeralds initially think that Mary is the warm ghost, and Carmel the cold ghost endangering Stella, but a séance proves them wrong. Carmel, the warm ghost and Stella’s biological mother, refused to be silenced and unfairly maligned, instead returning to tell the truth, while Mary, the cold malevolent ghost, tried to prevent the exposure of family secrets about her true nature and adoption of Stella after Carmel gave birth in secret. In life, Carmel had been a nurturing mother who truly loved Stella, and Mary had been cold and uncaring, as well as asexual. Rick symbolically kills the “evil mother” Mary, banishing her ghost through ridicule, while Stella’s acceptance of the truth about her biological mother’s identity allows her to move forward and ensures that Carmel will no longer haunt the house. Commander Beech dies, and the film concludes with Rick announcing that he and Stella will marry, while Pamela will marry a local doctor who helped solve the mystery. The final frame shows the two couples together in the drawing room; Stella appears rather uncomfortable, with a forced smile, recalling her discomfort when Rick forcefully kissed her earlier in the film. Whether this was a directorial decision or simply reflective of the limitations of the young Gail Russell’s acting remains uncertain, but it opens up the happy ending to alternative interpretations, as is often the case in Gothic romances.

Dorothy Macardle used a ghost-story plot and Gothic conventions to frame a narrative about troubled marriages and mother-daughter relationships, family secrets that haunt the present, and transgressive sexuality, thereby setting up a critique of domestic ideology. The unsettling implications of such a critique in Gothic romances, though, are foreclosed by conventional endings in which the heroine embraces marriage and domesticity. While the novel refers to several alternative relationships and domestic arrangements, these are closed off at the end in favor of “normalization.” Although Stella has been traumatized by her upbringing—her grandfather was overbearing and repressive and her parents’ marriage was characterized by hatred and power struggles—her impending marriage to Rick is a foregone conclusion that meets the narrative demands of the Gothic romance. However, some readers and viewers of Gothic romances find the endings unconvincing and read beyond the ending, and may imagine that the naïve, inexperienced Stella, like the nameless narrator of Rebecca, will find that her real problems begin with her marriage to an older man she hardly knows, leading to a new Gothic narrative in the formerly haunted house they intend to live in.

|

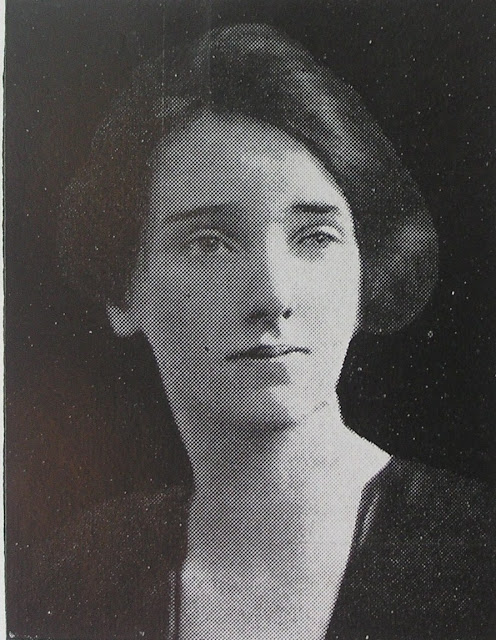

| Dorothy Macardle |

The Production Code affecting films in the 1940s meant that homosexuality, extramarital affairs, and out-of-wedlock births were referred to cryptically in The Uninvited to meet the imperatives of censorship. Viewers learn that Mary “feared and refused motherhood,” and is therefore blamed for her husband’s affair with Carmel. Mary, Carmel, and Miss Holloway are all punished for their respective sexual transgressions – asexuality, heterosexual promiscuity, and lesbianism – with death or, in Miss Holloway’s case, a mental breakdown. The character of Miss Holloway was recognized as a lesbian by the Legion of Decency, whose (male) leaders complained to Paramount executives about the scenes in which she speaks romantically to Mary’s portrait. Lesbian audiences in the 1940s also grasped the inferences and characterizations in The Uninvited, and film scholars note that it became a cult hit with lesbian communities in wartime America. Mary is depicted as asexual or possibly a lesbian by being non-maternal and too close to Miss Holloway, and the novel describes her as “unnatural,” tying in with discourses about motherhood and gender essentialism. Later film scholars have seen even more lesbian connotations, suggesting that the mother-daughter trope in the film can be a cover for lesbianism, since Stella has been in love with another woman, Mary, her whole life, much to Rick’s frustration.

Dorothy Macardle’s views on gender roles and motherhood were crucially shaped by her own family dynamics, and reflected in her Gothic novels. She perceived her English mother, Minnie, as a classic late-Victorian hysteric, or fake invalid, who used her fragility as a weapon to prevail in marital power struggles and prioritize her own needs, and viewed her Irish father, Thomas, as Minnie’s helpless and long-suffering victim. Her fiction is inattentive to alternative power dynamics in marriage; husbands are depicted as generally chivalrous figures vulnerable to abuse by manipulative women feigning fragility, rather than subjecting fragile, vulnerable women to abuse. Her novels all end with the metaphorical destruction of a malevolent maternal figure and her baleful power, suggesting that Minnie, like the vampires to whom a prominent Victorian doctor compared hysterical women, took a lot of killing. Macardle’s fiction overturned sentimental and politically useful Victorian notions of the mother’s gentle influence in the home, as her feminist convictions stemmed from the belief that women’s exercise of power should be transparent and directed outside the home. It enraged her that outwardly conformist women like her mother and the fictional Mary Meredith were praised for their virtue, and she tried to show the transgression and complexity behind simplistic notions of good and bad women in a novel in which an icon of conventional womanhood is exposed as a fraud.

The tensions and limitations of Macardle’s feminism and her use of hostile sexist tropes about predatory lesbians, frigid wives, and bad mothers in her fiction seem to stem not only from her understanding of her family dynamics, but also from her sense of herself as an Exceptional Woman, informed by social class privilege. She never married and spent years living alone or with other women, and spent some of her early life in female institutions, including an all-girls school and a women’s prison (for her Irish republican activism). While she enjoyed being a university-educated, professionally successful unmarried woman with no children, she thought most women should be wives and mothers, with their sexuality safely contained within marriage, a view shared by many interwar-era “maternal feminists” in Europe and the United States.

The two main (living) female characters in The Uninvited are Pamela Fitzgerald and Stella Meredith. Pamela demonstrates wit, assertiveness, and intelligence, especially when she solves the mystery of the two ghosts that had confounded the others. Stella is fragile and childlike, which greatly appeals to the older Rick. The circumstances of her upbringing have created a repressed, insecure personality who idealizes the vague memory of a loving mother. Despite Stella’s timidity, she demonstrates courage at the novel’s end when she confronts and reassures Carmel’s ghost. While normative heterosexuality is restored in the conclusion with plans for marriage, Rick’s love for Stella in the novel is unsettling, as he has constantly infantilized her and describes her as a child.

Miss Holloway, an “unfeminine” single woman and nurse who had been infatuated with her friend Mary and still worships her memory, is significant as a lesbian character in the days of the Production Code. Her name recalls London’s Holloway Prison, where suffragists were incarcerated earlier in the century, and the convalescent home she operates is a prison of sorts where female patients lose agency and autonomy. While Miss Holloway’s narrative seeks to contrast Mary’s moral perfection with Carmel’s depravity, the Fitzgeralds are so put off by this stereotypical sinister lesbian that they begin to think that things were not all that they seemed. The character of Miss Holloway shows The Uninvited’s indebtedness to Daphne du Maurier’s popular Gothic novel, Rebecca (1938; released as a film in 1940), as she bears a strong resemblance to Mrs. Danvers. Both are portrayed as sinister lesbians who idolize the dead woman at the center of the mystery and play a key role in reinforcing her iconization.

Overall, The Uninvited reflects a range of tensions and negotiations that intersected with contemporary discourses about gender, sexuality, feminism, and film censorship. While it falls prey to some hostile and stereotypical female characterizations common in the 1940s and later, it is complex and multilayered enough to allow for a range of readings and interpretations as it attempted to speak the unspeakable and represent the unrepresentable. Now that it’s finally available on DVD, maybe it will become at least as well known as The Uninvited: A Tale of Two Sisters.

———-

Nadia Smith is a historian and writer based in the Boston area. She is the author of Dorothy Macardle: A Life.

I’m 27 and this is one of my all-time favorite movie! I haven’t seen it in years though.

Definitely a good reading of the film! Thank you!