Written by Amanda Rodriguez

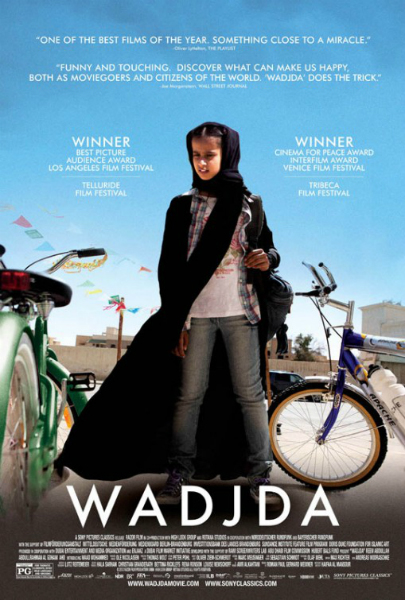

I’ve been waiting for Wadjda to come to my local Fine Arts Theatre for months so that I could review it for Bitch Flicks! Wadjda is noteworthy because it’s the first Saudi Arabian film to ever be directed by a woman, Haifaa Al-Mansour. At its heart, the film is about how young Wadjda, played by newcomer Waad Mohammed, navigates her culture and adolescence as a Saudi girl, her relationships with other girls and women, and what seems to be the changing attitudes of her country (more on all that later).

[youtube_sc url=”http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=3koigluYOH0″]

Personally, though, I was intrigued by the storyline of her new-found passion and desire for a bicycle.

Some background: I’m a late bloomer. I learned how to drive a car and ride a bicycle at the ripe age of 28. As a woman in my late 20’s, I became obsessed with learning to ride because of the freedom and exhilaration that the bicycle promised. The speed, the control, the sexiness of the road bike, the hint of danger, and the allure of the new experience all kept me riding clumsy circles around my parking lot with a neighbor friend holding the saddle (and therefore keeping the bike upright). For me, learning to ride a bike was not a matter of course as it was with most of the people I know, so I could identify with that longing for the unattainable that Wadjda embodies. Eventually, I learned to ride and became obsessed with it, pedaling my Bianchi 30, 40, 80 miles at a time. I also got really into following professional cycling (more on that later, too…I promise it’s relevant).

Director Monsour, herself, knows a thing or two about doing that which seems impossible. Though she had the permission of the Saudi government to make her film, she was forced to hide in a van for most of the outdoor filming, as it would be unseemly for a woman to give direction, especially to her male actors.

Monsour’s heroine also defies convention with her insistence on buying a bike to race her male friend, Abdullah.

Wadjda also wears brightly colored hair clips, Converse sneakers with green laces, and listens to American music. I find it somewhat troubling that Wadjda’s markers of rebelliousness are primarily associated with her exposure to Western culture, but her mother (a generation older) is a complex mix of culture and gender role compliance as well as rebelliousness: her daily work commute is three hours because her husband doesn’t want her working with men, she scolds one of her friends for not wearing a veil with her abaya, she claims Wadjda’s Western music is evil and that girls can’t ride bicycles because it will affect their childbearing abilities, she threatens frequently to marry Wadjda off, and when Wadjda must don a full abaya at the command of the school headmistress, she looks on with glowing pride as it is a treasured rite of passage.

On the other hand, Wadjda’s mother values her daughter’s happiness and ability to dream, she wears a nose stud, and she rejects the idea of her husband taking a second wife, willing to face drastic consequences if he doesn’t respect her wishes. This shows that over the generations, Saudi women are changing, with mothers imparting traditional values to their daughters while still giving them an increasing measure of freedom and autonomy. Monsour says of her own parents, “They are very traditional small-town people but they believed in giving their daughters the space to be what they wanted to be. They believed in the power of education and training. They taught us how to work hard.” Monsour also asserts that, “[P]eople want to hear from Saudi women. So Saudi women need to believe in themselves and break the tradition.”

I admit that when I saw all the women in the streets and in cars wearing full abayas, I was shocked at the imagery. I immediately perceived them as ghosts flitting through the public sphere with heads down, trying to escape all scrutiny, all notice. As a feminist, I bristled against these uniforms that hide the female form, declaring it taboo and the property of her husband. As the women sat waiting in a hot van with only their eyes visible, I realized, though, that the plight of women in Saudia Arabia isn’t that different from that of women in the US. It is a spectrum, with the US on the opposite end. Saudi culture insists women be completely covered, whereas US culture demands skin, cleavage, form-fitting clothing, and sexiness while simultaneously judging the women who do and those who don’t conform to that standard of femininity. Both cultures insist that the female body is a matter for public debate with the dominant patriarchy making the final judgment (as is apparent in US culture with the current backsliding on reproductive rights due to conservative male decision-making). The female body in both cultures then does not belong to individual women.

The strangely similar treatment of the female body in both US and Saudi culture brought up another intriguing comparison for me: women and bicycles. Abdullah (among others in the film) declare to Wadjda that, “Girls can’t ride bikes.” Now, you might think in the US we get off the hook because most little girls (unlike myself) do, in fact, learn how to ride bikes at an early age, and nothing is thought of it. However, how many of them are encouraged to become professional cyclists? Though there are plenty of American women just like Wadjda who won’t take no for an answer, who follow their dreams to become competitive athletes and cyclists, what does the cycling world look like for them? They’re grossly underpaid, under-represented, and there’s hardly any media coverage of their events. Female cyclists (and, in most cases, female athletes in general) aren’t taught to dream big like their male counterparts, and if they do actually achieve success in their sport, where does it leave them? Mostly, it leaves them in anonymity (do you know the name of the most acclaimed female cyclist in the word? doubt it, but I bet you know the name Lance Armstrong) without nearly the recognition, range of events in which to participate (there is NO female equivalent of the Tour de France), and their rate of pay is a mere fraction of that of male professional cyclists. In essence, US culture is telling us that girls can’t ride bikes. Think about that whenever you want to get all righteous on the Saudi gender inequality issue because we sure as hell haven’t gotten it figured out here in the States.

If there is one theme in Wadjda that cannot be overstated, it’s: The personal is political. In Wadjda, the story of a young girl learning to ride a bike has profound cultural, religious, and gender implications. Her stand is powerful and brave, but more importantly, she never questions the rightness of it. Wadjda never once doubts that she should be able to own and ride a bike. It takes many, many small, personal commitments and triumphs like Wadjda’s to build the foundation of a movement for change.

2 thoughts on “‘Wadjda’: Can a Girl and a Bicycle Change a Culture?”

Comments are closed.