This guest post by Kim Hoffman appears as part of our theme week on Cult Films and B Movies.

There are countless teen films with themes that focus on the ways young females work with, and then eventually against each other, for the sake of a number of factors: their place in a social hierarchy, a jealous feeling, or in summation, an overall insecurity they are plagued with because they’re sixteen and they haven’t yet developed a sense of self-awareness outside of their high school cafeteria.

What I’ve always welcomed in The Craft was the idea that a group of girls could be simultaneously contributing to the ongoing high school drama they’re faced with each day, while nurturing their powers on a higher plane that none of their peers could possibly grasp. Earth, air, fire and water—the four corners of the world, but incomplete without a fourth girl until character Sarah (Robin Tunney) begins attending her new Catholic high school and develops a friendship with the school witches.

In elementary school, slumber parties with girlfriends typically involved the game “Light as a Feather, Stiff as a Board.” It was a bonding experience between us girls that didn’t quite mean we believed we could actually make one another float, or invoke a spirit to talk to us through a candle or the Ouija board, but perhaps that very hyper-adolescent female clout was a presence in itself, an ember growing hotter within us, if we dared pay attention. Boys in class picked me on—one called me “Casper” because I was so pale. I was living in Florida at the time and all of the other girls were tan and flirted with boys by dumbing themselves down. I didn’t subscribe to that diluted mindset. I was determined, even as a confused pre-pubescent girl with a deep shyness in me, to move to the beat of my own drums, however weird others thought I was.

The understood leader of this teenage coven in The Craft is Nancy (Fairuza Balk), a girl who stands up to the likes of other mean girls in teen drama history like the most cruel of Heathers or Rose McGowen’s unapologetic lipstick machine Courtney Shane in Jawbreaker. Next to Nancy are Bonnie (Neve Campbell) and Rochelle (Rachel True). Bonnie is scarred with terrible marks on her back, causing her to be shelled and quiet, uncomfortably covered up so no one can see her, fraught to feel beautiful. Rochelle, an African American athlete with a sweet and open disposition, puts up with torment from a girl named Laura Lizzie (Christine Taylor), a popular blonde who makes terrible racial slurs at her. Nancy and her mother live in a dilapidated trailer with her sickening and habitually abusive stepfather. There’s a feeling hanging in the air when Sarah begins to show signs of telekinetic power; the girls know their coven could be complete and that their powers joined could change everything they can’t currently control.

After popular boy Chris (Skeet Ulrich) asks Sarah out on a date and she agrees, she’s angry to find out that the following Monday at school, a terrible rumor has been spread about her and Chris having sex on that date—despite the fact that they absolutely didn’t. As a result, the three other girls approach her with an idea, a spell. They cast a spell to make Chris do whatever Sarah says. And it works. He’s now following her around like a lost puppy, and Sarah’s slut-shaming rumors are put to rest. It’s a moment of reckoning, wherein a bad school rumor at the hands of a guy is twisted to his disadvantage, causing him to be the weak, demure one that he attributed to Sarah, banishing his ego and putting Sarah in power. But is it power for women, or is it power modeled after male dominance?

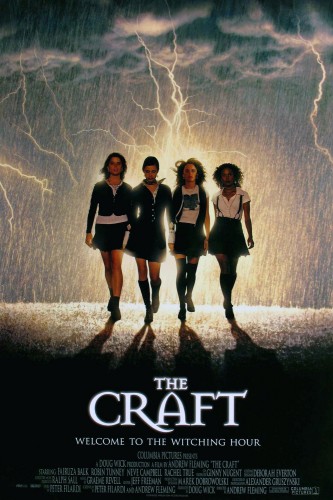

Now fueled with delight, greed and confidence, the coven is a complete dynamic troop, marching through the hallways in their Catholic school-girl uniforms, evoking a new brand of strength that makes their school mates fear them even more, which they love and welcome. Nancy’s face says, “Look at me, I dare you.” It’s the high point in the film for these girls, as they’ve joined their powers to reclaim their place, to restore their souls—but as quickly as that power is recognized, they begin to misuse it for revenge—a yin yang of dark and light that must bring chaos if used too recklessly.

The girls perform a healing spell on Bonnie, who only wishes for her scars to be gone. At her next doctor’s appointment, Bonnie, her mother and the doctors are stunned to find out that when they peel back her bandages, her back is completely healed. The next day at school, Bonnie walks in with a new outfit, a new attitude, and an outward vivaciousness that all can see. Of course, the boys take notice—but this is about Bonnie, for Bonnie, and no one else. Simultaneously, Rochelle is handling Laura Lizzie, who is still taunting her in the locker room. Over the course of a few days, Laura finds her hair is beginning to fall out in her hairbrush and in the shower—and it’s only becoming more and more atrocious. Finally, Nancy causes her stepfather to have a heart attack and die. She and her mother are left with a booming inheritance and can move out of the trailer into a swanky new high-rise condo.

The Smiths’ iconic “How Soon Is Now?” echoes in the background, and the girls, who call upon a deity named Manon, host a ritual in attempt to invoke the spirit within them. What they don’t realize is that Nancy has a plan to take Manon into herself completely, a dark power that the woman at the magick shop they frequently steal from knows is not the kind of magick that amateur witches should mess with without proper practice. The crone shop owner however recognizes Sarah is different from Nancy and the others, a consciousness that rises above the girls who have impulsive, quick-tempered intentions.

Inside the traditional current of teen film subtext in which we root for the new girl/the odd girl out/the girl with the chance to teach something/the girl who has been influenced by the luster of a life she is told will make her more popular, Sarah must defeat the soul-sucking people who seek to make her an object. We root for her because we see what she can’t see yet, and we know that something terrible might have to take place in order for her to come to fully developed realizations that push her into making important choices. This isn’t about making an A; it’s about making sure you aren’t burned at the stake for your high school to witness.

The Craft presents a lesson that coming-of-age films don’t typically make a point to show. A ballot is cast for prom queen or SAT prep sits on the horizon with college days looming, a girl must get a boy to like her, losing her virginity in the process. But this film is about serving the self—the craft of empowering oneself to surmount the archaic persecutions against women—taking back the threat of female power. But like a genie in a bottle that allows three wishes, this craft must be practiced and understood, respected completely before it can be outwardly used, or else it will perpetuate transgression.

The mystery of women, our cyclic connection to the moon, to medicine, math, written words—it has all been condemned and misappropriated as voodoo, black magick, devil worshipping, witch work. To many, witch means bitch. Bitch means witch. What is unconventional is evil. But ego is genderless, and it feeds a darker realm. The people who attack and target Sarah, Nancy, Bonnie and Rochelle represent that gender-neutral aspect that aims to banish female power. The age that is dawning doesn’t require school texts and chalk boards. The real war taking place requires ritual books and goblets filled with blood and wine, you know—typical high school material.

However, Sarah’s spell eventually backfires when Chris tries raping her at a party because he will stop at nothing to be near her and can’t wrap his head around these feelings he can’t part with. Nancy saves Sarah by throwing Chris out of the window with her powers, and he is killed. Despite the harm he has caused, Sarah is mostly just scared of Nancy now. It’s a turning point in the film when the roles shift and the people against them are not the ones to be feared—it’s the girls themselves that have to come face to face with their own shadows.

After Sarah tries casting a binding spell against Nancy to prevent her from causing harm against herself and others, the girls turn on Sarah. As a real life outcast who was banned from my own in-crowd group of girl friends in middle school, I see this as a blessing in disguise for girls who are meant for bigger things. It’s a calling of sorts—a low hanging cloud that beckons you away from cliques, from being another follower, from believing in something just because someone tells you its real. What about believing in you? Sarah has had the power all along—Nancy knew it. So she muddled Sarah down in the hopes she could overcome her and maintain what would only ever be a false sense of supremacy. All Queen Bees are only as strong as their weakest link; they can’t survive alone.

In the final act, Sarah and Nancy come head to head, Nancy filling up Sarah’s house with snakes and creepy crawlers, attempting to influence Sarah to commit suicide—the ultimate female betrayal in which Sarah’s death is the only means for Nancy to move forward. Motivated by life and a true sense of power that musters itself back to the surface, Sarah defeats Nancy and thereafter Nancy is sent to a mental hospital. We’re left with a few lingering feelings and questions. Most prominent is the feeling that good can defeat evil and that female power is strongest when the belief is in oneself, not what they’re told to follow. But what does this say about a coven of women? Can women work together without turning on each other? What factors would dispel women from competing over control and success? Is The Craft a lesson in the art of witchcraft, or is it a deeper lesson in the very real and everyday transformation we make from girls to women?

Kim Hoffman is a writer for AfterEllen.com and Curve Magazine. She currently keeps things weird in Portland, Oregon. Follow her on Twitter: @the_hoff.

interesting analysis of this underrated film. too often women come together and, maybe partly because of the lack of opportunities, competition and jealousy occur. then they turn on each other. at least, this seems to be popular opinion.