This guest post written by Eva Phillips appears as part of our theme week on Women Directors.

[Trigger warning: discussion of rape and sexual assault]

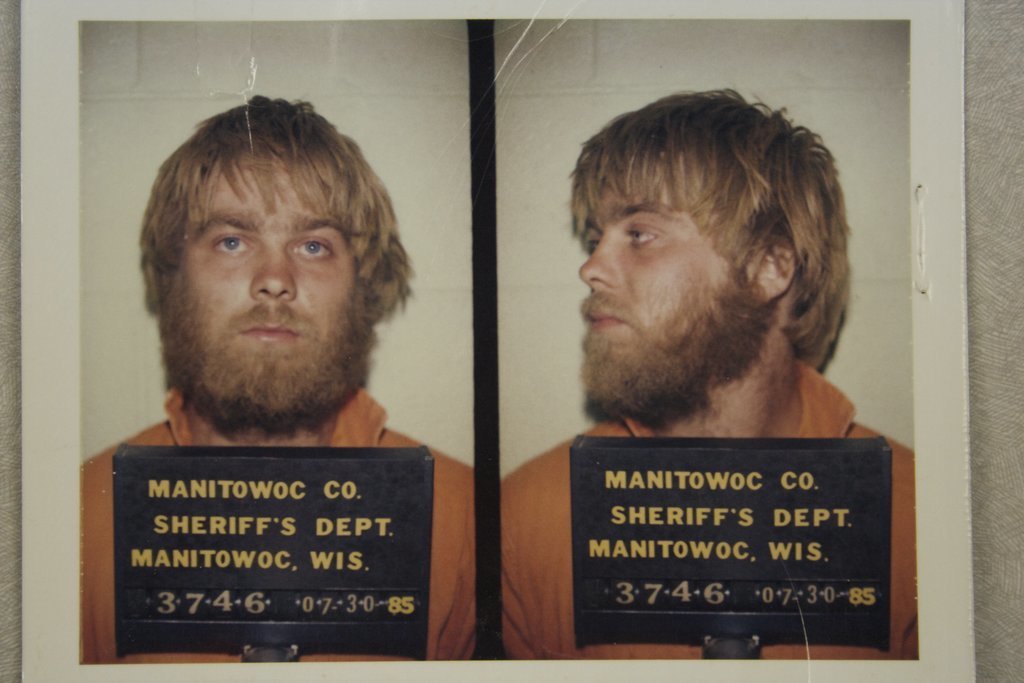

Within the first five minutes of both Fantastic Lies (directed by Marina Zenovich) — the most recent, methodically investigative installment of ESPN’s documentary film series, 30 for 30 — and Making a Murderer (directed by Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi) — the outlandishly popular and blisteringly sensational Netflix original series — impressively grand, birds-eye-view tracking shots are presented of the respective towns that played stage to the respective crimes at the center of the documentaries. Quietly idyllic and quaintly derelict, these introductory shots of Durham, North Carolina — home to Duke University and the young men of the Duke Lacrosse team accused of rape in 2006 — and Manitowoc County, Wisconsin — otherwise unknown home of Steven Avery, accused and exonerated of sexual assault in 1985 and re-indicted for first degree murder in 2007 — are not unfamiliar documentary tropes. However, solidifying their provocative and distinct styles and points of view, the ways in which these women employ their aerial shots of small towns, soon to be ravaged by controversies, are testaments to their acumen, and the disturbingly contentious nature of their films.

The shots would be otherwise unremarkable were it not for the stark juxtapositions and establishing of voice that the cinematic techniques achieve, and what they subtly intimate about the women helming each project. For Moira Demos and Laura Ricciardi, the sweeping captures of Manitowoc County and the labyrinth-esque junkyard owned by Avery’s family (and alleged site of the 2005 murder of Teresa Halbach) are part of the opening sequence of every episode of Making a Murderer, and are interposed with childhood photos of Avery, extreme close-ups of the decaying Avery home, and portentously ironic court documents and police officers. In the series first episode, these tracking shots nestled in the opening credits come directly after home footage of Avery’s release after his exoneration in 2003, that is jubilant, liberated, but haunted by his cousin’s premonition that, “Manitowoc county is not done with you…they are not even close to being done with you.” In Marina Zenovich’s opening frames of Fantastic Lies, the tracking shots of Durham are prefaced with videos of the Duke men’s lacrosse team suffering an emotional championship loss to Johns Hopkins, and embedded with interviews of parents lauding the boys determination to succeed, and North Carolina Central University professor Shawn Cunningham anthropomorphizing Durham as a city desperately trying to find its identity.

Demos and Ricciardi and Zenovich, by using traditional, seemingly innocuous aerial tracking shots of two towns interplayed with foreboding soundbites and poignant videos, achieve a narrative perspective that is as provocative as it is subdued. Creating worlds in which easily reviled or vilified men are at dire odds with (metonymic) towns that detest their very essence, Demos and Ricciardi and Zenovich as occluded intermediaries — they can at once see the entire town and infiltrate its intricacies and complications, and they can expose the inner workings of their subjects, their virtues and foibles. These women not only position themselves as intermediaries, but as exculpatory executors specifically of men otherwise caricatured and reduced.

What is most remarkable and perhaps most subversively compelling about both Making a Murderer and Fantastic Lies, and about the intentions and directorial choices of their respective creators, is that neither documentary endeavor chronicles the sagas of particularly defensible — or even, to some, at all likable — men. The alleged perpetrators in each case are from radically different socioeconomic strata (the small town, meagerly educated Avery would balk at the world of the uber-affluent, high-pressure Duke students), though both suffer fraught relationships with the law — the young men at Duke accused of rape but eventually cleared of any guilt; and Steven Avery, though erroneously charged with rape, is now serving a life sentence for first degree murder. But what the men most noticeably share is their almost archetypal “bad guy” aura, and the simultaneously unflinching and accommodating manner in which Demos and Ricciardi and Zenovich display every facet of their subjects.

Arguably dealing with more of a moral quagmire (despite their now being cleared of the charges), Zenovich, who brilliantly tackled an equally problematic man in her 2008 Roman Polanski: Wanted and Desired, opens her film with the barrage of soundbites, even from Duke alum Dan Abrams, citing the brash braggadocio of the men on the lacrosse team — their elitism, their “cockiness,” their hulking physiques and awareness of social prestige, their perpetuating “golf culture with an attitude.” Indeed, as the film progresses, unfolding in the manner the news media first exposed the case, Zenovich leaves no factual, disconcerting detail uncovered — the notorious raucousness and drunken offenses the team was known for; the fact that the boys held the party and intentionally hired exotic dancers (though, the detail of the boys requesting white dancers is skirted away from) and in the throes of profound inebriation, brandished a broomstick in a sexually suggestive manner and spewing racial epithets. Even the outrageously inflammatory and derogatory email — in which a player, referencing American Psycho, “jokingly” tells his teammates he is going to murder, flay and desecrate strippers — is discussed.

But amidst the revelations of the perniciousness of the men’s behavior, Zenovich carefully and seamlessly weaves in tearful, anguished testimonials from the parents of three boys (Reade Seligmann, Colon Finnerty and David Evans) falsely identified by the alleged victim, Crystal Mangum, and stalwart admissions of miscarriages of justice by former teammates. As Zenovich masterfully reaches the climax of the film, gradually and organically constructing doubt as she eventually depicts the overzealousness of prosecutor Mike Nifong and the dearth of physical evidence that would exonerate the players, the boys have been valorized. Moreover, the town of Durham, once an aerial shot at the beginning of Zenovich’s film, is micro-analyzed and cast as the embittered and disenfranchised foe of the boys, represented and led astray by the deceitfulness of Nifong. Zenovich presents a fractious clash of worlds in which a team of white, safeguarded men have the names slandered and privileged unhinged, and emerge triumphant victims.

In true subaltern treatment, Crystal Mangum is dissected by friends, and never speaks (though, as Zenovich shows, the prison where she is being held for an unrelated second-degree murder refused to let her speak to Zenovich despite her desire to) except for recorded media confessions and apologies of her false accusations. Her supposed instability is extrapolated upon, coupled with repeated shots of photos of her staggering and falling at the party. However, Mangum still “stands by her story” of surviving sexual assault and ten years later, speaking to Vocativ, “she maintained that she was assaulted.”

Demos and Ricciardi, whose Making a Murderer project was an arduous, ten year, post-graduate venture (rather than Zenovich’s year long, at times thwarted immersion into the lacrosse scandal), understandably present a much more involved, complicated portrait of their male subject, Steven Avery (and to some extent, his imprisoned cousin and alleged co-conspirator Brendan Dassey). Certainly lacking the prototypical self-impressed, egotistical athlete reputation that adulterated much of the Duke handlings, Avery, as Demos and Ricciardi briefly show (through exquisite cinematography, using letters and rare reenactments, one should add) was plagued with his own demons — arrests for animal cruelty, disorderly conduct, aggressive behavior towards relatives (which, arguably, would spur the false rape conviction), and violent, disquieting threats written to his former wife while their marriage dissolved. Yet in the hundreds of hours whittled down to the expertly directed series, Avery, while often maligned, seemingly simple-minded, ill-behaving but not necessarily menacing, is always shot through a sympathetic (often, emphasizing the pathetic) lens. Much of this is testament to the directing duos unfettered commitment to showing the complete multifariousness of the case as they lived each moment with the family, dedicated to Avery’s case for a decade from the moment they stumbled upon the now infamous New York Times front page article. And much of the fixation and implicit empathy for Avery is a result of Demos and Ricciardi’s pursuit to hyper-focus on the failures of the justice system. But much like Fantastic Lies, Avery (and more pitifully, Dassey) is positioned, much more effectively, as a steamrolled victim of law and order run amok, and a town’s collective antipathy for a man and his family (for much different reasons than with the Duke boys) galvanizing the destruction of a man’s life.

Similar to Fantastic Lies, too, is the quiet lionization of these men in the wake of crimes (whether they are irrefutable or exaggerated and falsified) against women who are noticeably underrepresented in the documentaries. Teresa Halbach, whose body is found on Avery’s property after taking photographs at his junkyard for a car magazine, is shown only through aching archival footage; her family, primarily represented by her brother (who, as a rabid Making a Murderer conspiracy theorist, I find to be suspiciously portrayed), is a minimal presence at best. Though the duo beautifully achieve a scornful eye at the fallible justice system and the prevailing sentiments castigating Avery, a looming partiality ripples through Making a Murderer that problematizes the series as an exculpatory venture.

It should be noted that I am an ardent fan of both Zenovich’s and Demos and Ricciardi’s projects. Foremost I am thrilled that not only two women, but two queer women in a relationship helmed the wildly popular Making a Murderer. Furthermore, I was riveted by its reinvigoration of my childhood fascination with crime sagas, with Demos and Ricciardi’s nuanced and meticulous style, analysis of every detail, and penchant for the gorgeously tragic. Their flawless removal of themselves — seemingly something unachievable by the more egomaniacal strain of sensationalized male documentary filmmakers — but consecration of their voices is haunting, and a tribute to their years of investment and toil (through which, I am flabbergasted, they preserved their loving relationship). I too am elated, and to some degree relieved, a woman directed the masterful reflection on the Duke scandal — an imbroglio I witnessed with conflicted emotions, as a teenager beginning to develop my feminism, as a lacrosse player of eight years, as someone who knew players on the team.

Certainly, these analyses of the bungles and undeniable violations on the part of the justice system need to be examined, and it is a boon that these women take part in the burgeoning presence of women documentary filmmakers (though still infuriatingly small compared to male counterparts). Certainly, too, Demos and Ricciardi and Zenovich fastidiously show how individuals’ agency is stripped, and their identities elaborately reconstructed by tendentious external powers (media, the legal system, troubled communities). But the lingering effects of these projects, of the specific focus on men in tempestuous situations, and the resonations of these exculpatory endeavors leaves unease. It is the unease that pinches when the only individual to mention the dangers to rape survivors after a false accusation is a media fiasco is a strong-jawed, former Duke lacrosse player on the team during the incident. It is an unease that is as profoundly discomforting and ambiguous as the elements at play in the discombobulated and life-altering cases these women so extraordinarily portray.

Eva Phillips is constantly surprised at how remarkably Southern she in fact is as she adjusts to social and climate life in The Steel City. Additionally, Eva thoroughly enjoys completing her Master’s Degree in English, though really wishes that more of her grades could be based on how well she researches Making a Murdererconspiracy theories whilst pile-driving salt-and-vinegar chips. You can follow her on Instagram at @menzingers2.

1 thought on “‘Making a Murderer,’ ‘Fantastic Lies,’ and the Uneasy Exculpation Narratives by Women Directors”

Comments are closed.