This guest post written by Allie Gemmill appears as part of our theme week on Women Directors.

What is it about Maya Deren that continually lures viewers to her body of work? Is it the enigmatic images that comprise her films? The depth of her symbolism? The notably non-mainstream depictions of the female form and psyche? Perhaps it is all of these things. One thing is for certain: Deren was unlike any woman working in film during the first half of the twentieth century. Consistently cited as a revolutionary in cinema, Deren lived and breathed the lifestyle of a working intellectual. She was seemingly cut from the large swath of men working in the postmodern arts of the WWII era and yet destined to re-shape it.

It’s easy to forget that there were active movements of artistic change working in film in the 1940s: Among the hard-boiled crime noirs, screwball comedies and heroic war epics being pumped out by Hollywood, there was also an equally tangible thrust towards surrealist and avant-garde aesthetics in film. The European approach to Surrealism, Dada and Futurism were swirling and manifesting into one great push towards what would be recognized as a post-modern art movement in America.

Well-educated and well-versed in the arts, Deren’s first foray into the arts was as a dancer. But her restlessness in dancing meant she did not succumb to traditional trajectories like her female peers — often settling to be chorus girls or struggling actresses. When it came to art, she was compelled to fulfill her own vision. The themes and ideologies she worked into her films are direct product of the culture in which she was working, yet it was wholly unlike anything being exhibited. Questions surrounding the social, spiritual and psychological place of woman are at the heart of Deren’s films. She was working against the Hollywood machine, against a male-dominated art form and against socio-normative ways of portraying the female self. This is what makes Deren so notable: her films deal with the uniquely female issues of time and the body in a considerate and challenging manner.

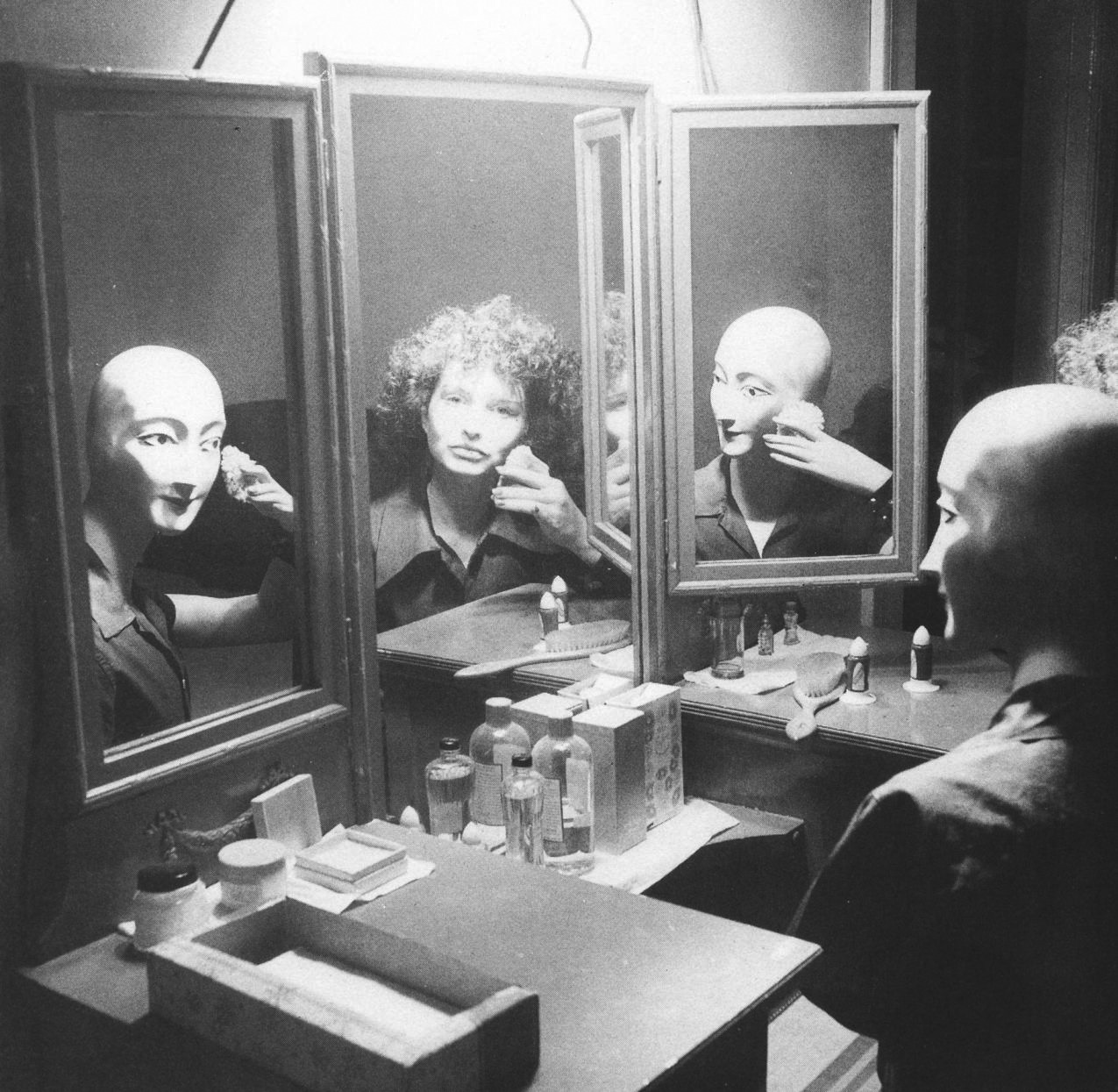

Deren’s rejection of the Hollywood machine fully emerges in her style, editing, storyline and characterization. Her push towards re-contextualizing the female body in relation to space and time can still strike us as wholly fresh and challenging. Her most famous work, Meshes of the Afternoon becomes, in this way, a reading of a woman working with and against herself through splitting into multiple iterations of herself. Most importantly, the film unpacks the notion that not only is the dream-landscape of a woman complex, it is bound tightly to her, defining who she is and guiding her constantly through the world like a compass.

In the documentary In the Mirror of Maya Deren, Deren’s voiceover speaks carefully to us:

“What I do in my films is very distinctive. They are the films of a woman and I think that they’re characteristic time quality is the time quality of a woman. I think the strength of men is in their great sense of immediacy. They are a ‘now’ creature. A woman has strength to wait because she has had to wait. Time is built into her body in the sense of becomingness. She sees everything in terms of the stage of becoming.”

Who or what does Deren become in Meshes of the Afternoon when time reconfigures her mental and physical self?

In Meshes of the Afternoon, we are presented with a simple mystery: What is haunting Deren and why? Is she dealing with real or imagined trauma? In order to find the true answer, we watch as time breaks Deren apart. Fragmenting her real body into multiple dream bodies, she must reassemble herself in order to understand herself. What we find out is that freedom is the separation of herself in life — through death — from the man who has tethered himself to her. He has brought her into a home which now feels destructive and alien to her. The key to release is, ultimately, death, leading her to the dreamlike sea, away from the claustrophobic villa that was slowly destroying her.

The film uses rituals here to better tease out the idea of how a woman can find release from a problem; in this case, the problem of a restrictive relationship. As Deren’s multiple selves enter into the house, examining the abandoned and cluttered space, they work in concert to work out the best means of release. With each step closer to the solution, the dream seeks to throw Deren off the scent, to disorient her enough to wake up back to the comfort of romantic confinement. To what lengths is she willing to go to be free? We watch the key and knife presented repeatedly. The women sit as the table, each representing a different path and trying to take the key to fulfill a separate purpose. Is escaping the confines of this house, and by extension the relationship best done with a key to open a doorway to a new world, to step into a better space? Or is it a knife to both destroy and release that which hurts her so deeply? More importantly, will the hooded figure be the person to release her or further harm her? Ultimately, it is only through death (decided through much struggle) that she can free herself and find freedom in the open waters of the afterlife.

What makes Meshes of the Afternoon so vital is not only its toying with a traditionally linear time narrative, but also its critical characterization of the fraught nature of a woman solving a problem so often attributed to her gender: the role she must play in a romantic relationship. By illustrating the doubts and confusions that occur when a woman comes to a love-based impasse, the film seeks its resolution in the psychological complexity that is woman herself. For if women are heteronormatively socially programmed to devote their entire being to the care and love of a man, then Meshes of the Afternoon makes the argument that a woman must find complete physical, mental and spiritual release in order to find herself again. The woman here feels so constricted and defined by a relationship that she must seek a dramatic escape. In her home, in her body and in her romantic life, she is caged. Released through death is what a woman becomes as time ekes out its purpose to weaken the female self.

We can appreciate that Meshes of the Afternoon is different in nearly every way from the typical cinematic fare of 1943. Deren’s thorough rejection of narrative made way for audiences to experience the psychological drama of a woman. In both this film and her successive short films, Deren vitally infused the fraught, passionate, dreamlike, maniacally repetitive and deeply complex nature of woman into each frame. In reframing female issues through the repurposing masculine art forms, Deren cemented herself as an eternally important female artist and director.

Allie Gemmill is a film journalist based in Tampa, FL. She is the founder and creative director of The Filmme Guild, a feminist film salon dedicated to examining the intersections of women and film. Follow her on Twitter and Medium.

1 thought on “Female Becomingness Through Maya Deren’s Lens in ‘Meshes of the Afternoon’”

Comments are closed.