Last October, Stephanie reviewed Rachel Getting Married after seeing it in the theater. After rereading her post, I’d like to offer my response.

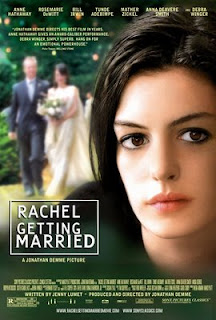

First, the poster is a poor representation of the film. While you could argue that Kym (Hathaway) is the main character, the movie is really about her and her sister, Rachel (DeWitt). The background of the movie is much more in the foreground, unlike the poster. All the characters in the film are complicated, conflicted, and ultimately complicit in the family tragedy. What Stephanie said about the anger and guilt rings true, as well as the unsentimental nature of the story. Each character behaves in cruel, selfish ways; Kym’s narcissistic, inappropriate speeches counter Rachel’s bratty outbursts of jealousy. Yet there are some weak points in an otherwise very, very good movie.

First, the poster is a poor representation of the film. While you could argue that Kym (Hathaway) is the main character, the movie is really about her and her sister, Rachel (DeWitt). The background of the movie is much more in the foreground, unlike the poster. All the characters in the film are complicated, conflicted, and ultimately complicit in the family tragedy. What Stephanie said about the anger and guilt rings true, as well as the unsentimental nature of the story. Each character behaves in cruel, selfish ways; Kym’s narcissistic, inappropriate speeches counter Rachel’s bratty outbursts of jealousy. Yet there are some weak points in an otherwise very, very good movie.

The mother, Abby (Winger), always stays on the periphery of the story, with both sisters desiring her comfort and love.  Her inability to give her daughters what they want is realistic, but in a film where the two main characters change over the course of a weekend, and grow to accept each other in subtle ways, an unchanging, hard mother stands out and takes on the role of the ‘responsible party’ in the family’s tragedy. Her coldness and distance, compared to the father’s overbearing nurturing of his daughters (he’s constantly stroking faces and fixing food), makes her an easy target for blame. The reversal of stereotypical gender-based reactions to tragedy is particularly interesting, but I wonder if the flip is too complete, too easy. In other words, does the mother simply become the father? What kind of love are the sisters looking for from their mother? Do they need something from their father? If so, what?

Her inability to give her daughters what they want is realistic, but in a film where the two main characters change over the course of a weekend, and grow to accept each other in subtle ways, an unchanging, hard mother stands out and takes on the role of the ‘responsible party’ in the family’s tragedy. Her coldness and distance, compared to the father’s overbearing nurturing of his daughters (he’s constantly stroking faces and fixing food), makes her an easy target for blame. The reversal of stereotypical gender-based reactions to tragedy is particularly interesting, but I wonder if the flip is too complete, too easy. In other words, does the mother simply become the father? What kind of love are the sisters looking for from their mother? Do they need something from their father? If so, what?

Aside from what I see as the incomplete characterization of the mother, something that really bothered me is something I simultaneously love: the lack of back story. While it makes us more present in the film, it endlessly thwarts attempts at a reading. The documentary-style filming, too, frustrates viewers by hiding as much as it reveals. The family trauma is made abundantly clear, maybe too much so. In the first scene, we learn from a fellow rehab patient that Kym killed someone with a car. Once she gets home and stands for a moment in an empty child’s room, we can guess what has happened. We get several additional scenes that explain every detail of the accident. Yet, that’s not the source of her addiction. Kym was some sort of teen model, gracing the cover of Seventeen magazine while blasted on horse tranquilizers, and her family had the kind of money (whether it was hers or not) to send her to the premium rehab facilities.

Also, it’s impossible to ignore the multicultural cast of friends and family. We don’t know how a Connecticut WASP family came to be part of such a rockin’ crew, or how the bride and groom’s families all became so comfortable with each other on their very first meeting.  While I admire the post-racial aspirations of the film, and thoroughly enjoyed the music, the actors seem more like Jonathan Demme’s crew than two families joining for the first time. The mixing of cultures (Caribbean and Hindu, specifically, with those intimate with “Connecticut’s complicated tax structure”) plays naturally in the movie, and never feels like a co-optation, but compared with the stark realism of the primary relationships, leaves viewers asking questions, testing our willing suspension of disbelief. I’d love to read the screenplay (written by Jenny Lumet), and see how my issues with the film manifest in the (original) script, and how much is Demme’s indulgence.

While I admire the post-racial aspirations of the film, and thoroughly enjoyed the music, the actors seem more like Jonathan Demme’s crew than two families joining for the first time. The mixing of cultures (Caribbean and Hindu, specifically, with those intimate with “Connecticut’s complicated tax structure”) plays naturally in the movie, and never feels like a co-optation, but compared with the stark realism of the primary relationships, leaves viewers asking questions, testing our willing suspension of disbelief. I’d love to read the screenplay (written by Jenny Lumet), and see how my issues with the film manifest in the (original) script, and how much is Demme’s indulgence.

While this may seem like a negative review, the preceding are really my only complaints. I watched the movie twice, and liked it even better the second time around. I haven’t seen such a realistic family drama, with women who break common decency while ultimately remaining sympathetic characters. Further, I’m fascinated by stories that deal with the aftermath of the worst kinds of traumas, and that explore how we come to deal with the unfathomable, the unforgivable, and the unforgettable.

I definitely hear what you’re saying about the almost too-easy coming together of the families, but I also completely loved it. I loved that a film like this, with different cultures/races coming together, doesn’t remotely deal with that issue. It treats it as a non-issue. But maybe the absence of acknowledgment is problematic?

What I loved and respected about the film though, was that it’s almost the complete opposite of a Craig Brewer movie, where his(mostly) intelligent, intuitive treatment of race overpowers any discussion of gender. The difference in Rachel Getting Married is that, in dealing more exclusively with gender issues–I’d argue the film is mostly about the relationship among the women–the writer or director doesn’t feel any need or desire to exploit racial tensions, the way Brewer enjoys creating male characters who beat the shit out of women, or parade them around half-nude for 120 minutes.

(I hate him.)

It’s funny–I had mostly sympathy for the mother in this film. I saw her as someone who blamed herself to the extreme, so much so that she completely pulled away from her family; she could barely look at them, or stand to be in a room with them. She seemed, to me, a character driven by sadness and guilt. And I freakin’ LOVE that I could spend hours talking about the women in this movie, what drives them, how their individual complexities and the complexities of their interactions are what move the film forward.

Holla!

“In other words, does the mother simply become the father?”

The movie poster is interesting because it makes it seem like there is a tension between the sisters over the father’s love, a classic Oedipal narrative. Amber is right, however, that there is an interesting reversal of parental gender roles. The father is depicted as a stereotypical mother (the dishwasher is his domain), hysterical and obsessive to a fault, while the mother is a stereotypically absent father who is cold, distant, and for all intents and purposes, out of the picture (the step parents reveal this dynamic nicely: compare the step father-who says nothing to either of the sisters-to the step mother-who helps plan much of the wedding and feels empowered to speak her mind to Kym). My point is that the mother should be in the movie poster instead of the father.

I agree with Stephanie that the mother is depicted as complex; however, the DVD extras reveal a problematic twist. The director, Jonathan Demme, says that the mother (Rosemarie DeWitt) asked for more direction about the family dynamic that he politely refused to provide. He just wanted her to “go with it.” I find this problematic because, to me, it allows her to become the scapegoat for the sister’s reconciliation. The scene near the end where Kym’s interruption of the intimate embrace of the newlyweds is actually accepted by Rachel is the key scene of the movie. Rachel accepts Kym because the “real” culprit of the family’s trauma has now been revealed to be the mother (Kym even says something like “what mother disappears during her own daughter’s wedding?”…sure enough the mother leaves early to both daughters’ dismay). To me, Demme leaves the mother open to blame for Ethan’s death, or at least for abandoning her family instead of confronting the tragedy. The gender reversal of the parents thus becomes regressive: mom is always to blame for not keeping the family together. If a woman directed this film, DeWitt would have been provided more to work with. She would have been presented as more sympathetic. The problem is the sisters’ reconciliation would have been thrown into question.

We’re talking about Debra Winger, not DeWitt, right?

I don’t know– I didn’t walk away feeling like the film tried to argue that the mother was to blame for anything that happened. I did feel though, that the film really wanted to show that the mother, without question, blamed herself for everything that happened. So what does that mean?

I agree there’s an obvious reversal in traditional gender roles, at least in terms of how gender roles are traditionally portrayed in film.

But I mostly read the mother’s self-imposed isolation from the family as a product of society’s restraints on the mother–of course she feels guilty and blames herself; she let her child die.

It’s most interesting to me that the father’s reaction is to over-compensate with constant affection and validation, and I never get the sense from him that he feels responsible for the death of his son, at least not in the way you get it from the mother; there’s a constant apologetic nervousness in her, a formality that keeps everyone on edge.

So, while I suppose you could argue that the gender reversal reinforces that mom is always to blame, I’d argue that it actually illustrates further how harshly society judges women when it comes to their children. Childern are, after all, the mother’s responsibility.

Winger’s character blames herself so completely for what happened (because society holds the mother responsible, above all else) that, having failed them, she literally removes herself from her role as family matriarch.

Part of me wondered what the family dynamics were prior to the death of the son, mainly to assess what’s up with the dad. Was he always this over-the-top? I doubt it. I wonder if the son’s death (and subsequently, the mother’s metaphorical death) led the father to adopt this schtick.

Mostly though, I left the theater feeling that the son’s death broke the mother in a way it didn’t, or couldn’t, break the father, not because the parents were inherently gender-reversed, but because their genders inherently operate within two differing sets of accepted social norms.