Written by Leigh Kolb.

“What is beauty?”

“I have a thousand brilliant lies for the question.”

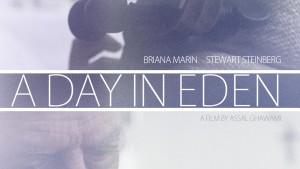

Assal Ghawami’s short film, A Day in Eden, quietly reflects upon the question of beauty. The first images we see in the film are in a nursing home–an elderly man in a wheelchair, a nurse roughly scrubbing a resident. The workers seem harsh, and the residents seem disconnected. All this unfolds as the narrator asks, “What is beauty?”

[youtube_sc url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Z6gDCer30wc”]

A volunteer cellist, Fereshde (Briana Marin), who is unmistakably conventionally beautiful, is led into the room of Mr. Hammacher (Stewart Steinberg). The nurse tells Fereshde that he has no friends or family. Fereshde, in her headscarf, sits and takes out her cello to play for him. There is a crucifix hanging above his bed. The contrast of youth and beauty and age and decay is clear in every shot. But the concept of “beauty” is much deeper than the skin.

Mr. Hammacher is angry and combative, but finds himself in an incredibly vulnerable position (even more so than before) when he soils himself. “Please don’t tell,” he says to Fereshde. “I just want to go home.” They embrace, and she gently, with great care and compassion, changes his pants. “It’s OK,” she says.

This moment, of course, is true beauty. They are vulnerable with one another, and that erases the walls that we constantly build up between generations, religions, and genders.

While she was making the film, Ghawami wrote about her work advocating for the Elder Justice Act (which became law in 2010). She said,

“To help pass this piece of legislation I produced and edited more than 50 interviews with victims of elderly abuse that were presented to Congress in 2010. I hope that A Day in Eden will continue to shed light on the issue of elder abuse and inspire more people to fight for the rights of our elders.”

On its surface, A Day in Eden is not overtly an activist film. The residents seem neglected and the workers seem cold, and we need to question how normal that seems. The deep humanity with which Fereshde treats Mr. Hammacher transforms him. Ghawami’s message is clear, then: only through compassionate humanity can we heal and be healed.

A Day in Eden is beautiful not only in its message, but also in its cinematography, editing, soundtrack, and acting. Beauty can be defined in a thousand different subjective ways. But A Day in Eden’s beauty lies in its truth.

Visit http://www.assalghawami.com/ for the director’s reel and upcoming screenings.

See also at Bitch Flicks: The Yellow Room and the Timeless Locking Up of Women’s Experiences

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature, and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.