Written by Mychael Blinde.

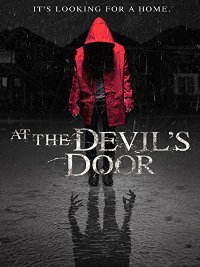

Many reviewers of At the Devil’s Door compare it to Rosemary’s Baby, and rightfully so: both films are masterpieces of pregnancy terror and the horror of unholy motherhood. But the women in these two stories have vastly different experiences accepting their roles as mothers of demonic spawn.

I’ll begin with a recap of At the Devil’s Door and discuss its weaknesses (the dialogue) and strengths (everything else, seriously this is a wonderfully horrifying film). Then we’ll take a closer look at the final scenes of both At the Devil’s Door and Rosemary’s Baby. There’s more than one way to mother a demon.

Trigger warning for suicide, sexual violence and demonic horror.

Spoilers.

Here we go…

The Recap:

Writer/director Nicholas McCarthy opens the film with a bold move: a key character making a big mistake. Bad choices are a bedrock of horror, but typically we’re eased into a protagonist’s poor decision. In Devil’s Door, we meet a young (teenage) woman who’s opted to sell her soul for $500 from a whackadoo creepster in the middle of a creepy beautiful California nowhere.

It’s the stupidest thing a person can possibly do in a horror film, and yet here we are, and somehow it works. The dialogue may be stilted, but the imagery is fantastic, both creepy and clever.

Before sealing the devil deal and claiming her cash, the young woman, Hanna (Ashley Rickards), must play three rounds of a shell game with the creepy guy. We viewers play the game along with Hanna, following the battered paper cups, forced to look long and hard at the screen, being primed for the the exquisite eyestrain of the horror to come.

We notice that she picks what should have been the wrong cups both her second and third turns in the game — and yet the piece is under whichever cup she selects. Shell games are notoriously played dishonestly as a con trick, and yet instead of being wrongfully made to lose, Hanna is wrongfully made to win.

“He has chosen you,” says the creepster, and in exchange for the $500, he instructs her to go to the crossroads and speak her name aloud.

It’s a bad decision, and very soon, Hanna is met with repercussions; she goes home and is horribly attacked by an invisible demon.

Then the film cuts to 20 years later and introduces us to Leigh, a real estate agent,

and her sister Vera, an artist.

The sisters care about but also appear uncomfortable with each other. Leigh is unable to have a child, and she seems to deal with the sadness and frustration at her infertility by encouraging Vera to find a man and start a family.

When Leigh is tasked with selling the house where Hanna lived during the days of her soul-selling exploits, scary things start to happen. In a return to Hanna’s story, we learn that she killed herself in her bedroom.

One rainy night while inspecting Hanna’s old house, Leigh encounters what looks like Hanna, but is actually the demon “wearing” Hanna.

It forces Leigh to experience a vicious seizure. Vera awakens from a nightmare — in which a levitating Leigh says, “It’s looking for a home” — to a phone call informing her that Leigh is dead.

Distraught by her loss, Vera begins to investigate her sister’s death, the history of the house, and its haunted inhabitant. Vera learns that Hanna, despite never having had penis-in-vagina sex, was pregnant when she killed herself.

Then Vera is attacked by the invisible demon, just like Hanna — except this time the demon flings Vera out the window from several stories up. At this point, Hanna and Leigh, Devil’s Door’s two other key characters, have both died. Did this film just kill its third key character?

Nope! Vera’s alive, and in one fell swoop of OMFG we see her wake up from a coma and learn that she’s eight months pregnant with demonic spawn (!!!). She insists on an immediate C-section and refuses to have anything to do with the baby.

Cut to six years later: Vera finally confronts her child, a daughter, with the intent to kill her. Her attempt is valiant, but ultimately, she cannot bring herself to plunge the knife, and so she resigns herself to motherhood.

The Film:

The horror of this film is awesome and intense and creepy and I will sing its praises up and down and side to side in just a few paragraphs, but for a brief moment, let’s address the film’s biggest problem: way super clunky awkward unnatural dialogue. It’s REALLY BAD, and it plagues the entire film.

In the introductory (and concluding!) voice-over, the little girl (Vera’s demon daughter) speaks ominously about the Mark of the Beast, which doesn’t seem to have any significant relevance to any other part of the movie.

When Leigh encounters the demon disguised as Hanna during an inspection of the house, Hanna looks at Vera’s picture on Leigh’s keychain, and Leigh says, “That’s my sister, Vera. She’s an artist. She’s a special person. Kind of dark. I just want her to find someone and have kids.”

Yes, this moment is made meaningful in the film’s final sequences when Vera assumes her role as the demon’s mother, but no, the dialogue does not need to unfold so awkwardly and unnaturally.

Nevertheless, I will forgive the dialogue’s shortcomings, because this film features a compelling horror story arc and a fabulous slow burn of quiet, yet terrifying scares.

The film does a fantastic job of depicting its monster primarily out of focus and in the background and the shadows.

While I disagree with a lot of this review at The Dissolve (“McCarthy’s sophomore project…doesn’t have any individually compelling characters” — WHAT), I am totally on board with the reviewer’s analysis of the cinematography:

“Virtually every frame in this film is designed for maximum dread. Every composition is deep with pockets of empty space that work to weaponize the audience’s imagination.”

This film thwarts horror fans’ expectations: We expect that the woman reaching into the barrel or the drawer will be grabbed, that the baby being watched by a demon will be murdered, that the spawn of Satan will be hideous, that Vera will kill her child. Nope. The women retrieve their arms unscathed, the baby’s fine, the demon infant is beautiful, and Vera resigns herself to motherhood.

This is not to say that nothing scary ever happens — quite the opposite, the entire film is terrifying. By raising expectations of specific scares and then withholding them, the film builds lots of tension but offers little release. This restraint renders the key moments of sudden in-your-face horror all the more terrifying.

And while the dialogue may be lacking, the film uses the absence of dialogue in key moments to great effect.

Hannah and Leigh and Vera — their stories overlap, yet they’re so disconnected from one another. Leigh has one encounter with Vera and one with Hanna, but the for rest of the film, she’s alone. Vera has one encounter with her demon girl.

At the Devil’s Door is about connecting with others, sometimes for good (sisters!) and sometimes for evil (demons!). There is a disjointed togetherness about the relationships of these three women and the way they impact each other’s lives, despite being so very, very alone.

At the Devil’s Door and Rosemary’s Baby:

Many reviewers have made connections between At the Devil’s Door and Rosemary’s Baby:

“A haunted-house story that eventually morphs into a pseudo-sequel to Rosemary’s Baby…” (The Dissolve)

“Who has the moxie to make it to the finale (which echoes a Rosemary’s Baby influence, to some degree)?” (Best Horror Movies)

“You’ve got lights going out, body possessions, levitations, Rosemary’s Baby-type pregnancies…” (Film Journal)

“McCarthy’s film has an obvious cultural ancestor in Rosemary’s Baby” (Syvology)

Rosemary’s Baby’s director, Roman Polanski, is an awful human being. Nevertheless, the film is one of the most iconic depictions of pregnancy horror, and the horror of unholy motherhood in our cultural consciousness. Its awesomeness is due mostly to its extreme loyalty to the text of Ira Levin’s original novel. The vast majority of the film – story, scenes, and dialogue — is taken straight from the book.

Rosemary’s Baby and At the Devil’s Door both feature a woman who is raped and impregnated by a demon, but who ultimately accepts her role as mother of the evil offspring. Despite their similar preggo-with-demon-spawn horror arcs, their stories are very different:

Rosemary’s Baby is a film about a long scary pregnancy; At The Devil’s Door features a sudden scary pregnancy. Rosemary wants to have a baby; Vera doesn’t. Rosemary accepts her child soon after he is born; Vera waits six years to confront her devil daughter. Rosemary never tries to kill her baby; Vera chases her daughter through the woods with a knife. Rosemary becomes empowered by motherhood; Vera becomes resigned to it.

My intention is not to argue that one representation is better than the other, but to examine the nuances of the two versions of the acceptance of an uncomfortable motherhood.

Let’s start with Rosemary:

Rosemary spends almost her entire story being pushed around (she is emotionally abused, drugged, raped, and impregnated), then finally, after giving birth, she takes control of her situation. With knife in hand, she confronts the evil coven who have violated her body, and she spits in her piece of shit husband’s face.

After witnessing the ineptness of the woman functioning as the baby’s caretaker, Rosemary exerts her power as the child’s mother, insists that the caretaker cease rocking the baby, and accepts her role as the devil spawn’s mom.

While the Rosemary’s Baby film is remarkably loyalty to the book’s text, the ending of the film departs significantly from the book’s ending. In the film, Rosemary wordlessly accepts the child. In the book, Rosemary not only confronts her malefactors, not only ousts the inept caretaker, but exerts her power over the entire coven, and over Roman, the coven’s leader, who orchestrated her rape and demonic pregnancy.

Here’s an excerpt from the end of the book, wherein Rosemary rejects the name Roman has given the child:

[Rosemary] looked up from the bassinet. “It’s Andrew,” she said. “Andrew John Woodhouse.””Adrian Steven,” Roman said

…

Rosemary said, “I understand why you’d like to call him that, but I’m sorry; you can’t. His name is Andrew John. He’s my child, not yours, and this is one point that I’m not even going to argue about. This and the clothes. He can’t wear black all the time.”Roman opened his mouth but Minnie said “Hail Andrew” in a loud voice, looking right at him.

Everyone else said “Hail Andrew” and “Hail Rosemary, mother of Andrew” and “Hail Satan.”

Hail Rosemary! The book presents Rosemary’s acceptance of motherhood as an empowering twist at the end of a story so focused on the horror of male control of female bodies. The film’s ending is less emphatic, but still presents Rosemary in a position of power within the coven, though still clearly under Roman’s control.

When Vera chooses to be a mother to her devil spawn, she gains neither control nor power. Vera doesn’t embrace motherhood — she does everything she can to reject it, to destroy it — but instead she becomes resigned to it. In the very last moments of Devil’s Door, Vera is silent, and finally the girl speaks: “I knew you’d come back for me, Mommy.”

Vera accepts her demon child, but only because she cannot bring herself to kill it.

Speaking of killing your demon child, let’s not forget Hanna, who was also impregnated, but who thwarted the demon by killing herself, and therefore the fetus. “I think Hanna killed herself before whatever was happening to her had a chance to finish what it was doing,” says Hanna’s childhood friend.

Vera is confined first by a coma and then a hospital; the devil doesn’t give her a choice but to birth the spawn. But Hanna has a choice, and she chooses suicide to stop her body from creating a human monster.

In both instances, the viewer is asked to root for a woman who is pregnant and who really really REALLY needs not to be pregnant. I appreciate films that put the viewer in the perspective of a person who needs an abortion (cf. The Fly, Prometheus). My hope is that these sequences plant a seed of empathy in audience members who don’t personally house a womb, who do not face the threat of unwanted impregnation.

Rosemary and Vera have different experiences taking on the role of mother to their devil children, just like different women have different experiences from each other when becoming mothers of not-demonic kids. Mothers are individual people existing in individual circumstances; no two experiences will be exactly alike. Stories about women who gestate demonic children explore the darker side of our cultural conception of birthing a baby and becoming a mom. Compared to Rosemary’s Baby, At the Devil’s Door offers a much bleaker view motherhood.

____________________________________________________Mychael Blinde writes about representations of gender in horror at Vagina Dentwata.

I’m kind of surprised about this review considering it’s on a distinctly feminist site. The author doesn’t seem to have any problem with the lack of consent on the part of the women who are ostensibly raped by a demon, forced to bear a child, and then “Vera resigns herself to motherhood.” Yes, possession narratives are usually about some violation, and with women characters, it’s almost always explicitly sexualized. Yet we live in a country where women have very little control of their own bodies and choices, and this film literalizes that problem and shapes it as inevitable?! This film has a lot of problems well beyond it’s dumb bracketing voiceover dialogue. Here again, we have a film where women are mere vessels for procreation, whether supernatural or otherwise. McCarthy’s first film, THE PACT, is better made and a lot less gender troubled.

I’m kind of surprised that you read my review and came to the conclusion that I don’t care if women are violated. To clarify, let me say that rape is horrible and inexcusable, always and forever.

The representation of rape, however, is different.

The representation of rape can be a good thing if it conveys to viewers how horrible and inexcusable the act of rape is. I think ‘At the Devil’s Door’ succeeds in representing rape as unequivocally evil.

“Yet we live in a country where women have very little control of their own bodies and choices” – yes, unfortunately this is all too true. But this film and ‘Rosemary’s Baby’ both show how utterly awful it is when women aren’t given a choice, when other beings violate our bodies and dictate whether and when and where and how we can access safe and supportive abortions or prenatal care. These films put the viewer in the perspective of a woman denied her own bodily autonomy, and they ask the audience to shudder at the horror.