This is a guest post by Rhea Daniel.

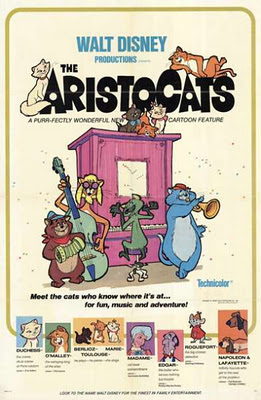

Madame Adelaide Bonfamille, a wealthy retired opera singer, lives in Paris with her cat Duchess and her three kittens Marie, Toulouse and Berlioz. Edgar the butler is surprised to learn that Madame, with no living relatives, plans to bequeath her entire estate to her cats and he is only second in line, all this after his service to her over so many years. Now that is a little unfair, but since the audience’s loyalty would be with the cute set of Aristocats, he becomes the villain when he decides to get rid of cat and kittens at the outset, drugging them and depositing them somewhere outside Paris. Edgar, compared to De Vil, is a bit of diluted villain, so his undoing offers little entertainment. The fun part begins when the Aristocats meet Thomas, a self-professed cat of the free world and make their way back to Paris with his help, meeting many a quirky character on the way.

But (and it’s a big one) in spite of having my undying admiration, Disney almost always manages to do something wrong. Disney’s humanizing its animals is part of its charm, but with that comes the inevitable pressing of human laws of behavior on to the jungle world—take Colonel Hathi bellowing, “A female leading my herd? Utterly preposterous!” in The Jungle Book (1967). Alright, so the Aristocats are household pets, they ought to have absorbed some of the human characteristics of their owners, but then Disney has always been unapologetically sexist, telling from its girls-can’t-draw-but-girls-can-trace rejection letters to aspiring female animators in its early years. The Aristocats aren’t far out of reach of this Disney cliché either. In recent times they’ve been trying to right several wrongs, but they’re still in the process. So, on the insistence that some things are just because, anthropomorphism in Disney cartoons is, safe to say, not just a reflection of the human world but also a reflection of Disney’s sexism.

In the original idea, Duchess isn’t denied agency and protects her children by moving from house to house to escape the villains. But true to Disney law, Duchess does little in The Aristocats beyond flapping her paws and calling “Marie! Toulouse! Berlioz!” every time they get into trouble. Perhaps she’s not used to the rough and tumble of the world outside, being an Aristocat and everything, but do her natural instincts emerge over time? No. Thomas comes along to do most of the work. Though Duchess is curious about Thomas’ world, she is incapable of getting her Aristocatic paws dirty, even if it is to save her children.

At this part when Thomas makes his entrance, though Duchess responds positively to his flirtation, I find his serenading and circling and gawking a tad creepy. I’m unaware if this is a cat ritual, but it so closely resembles human ones that I can’t help but judge Thomas as a bit of a creep. Duchess welcomes the attention with eye contact and by washing herself and giving that trademark Disney lowered eyelashes look. I notice that while her motherly instincts are conspicuously missing (aside from a few gentle admonishments) her sexual ones are intact, especially with her kids nearby. It would all be okay if little Marie didn’t think it was all terribly romantic. It’s cute and harmless when Marie is trying to be like her mother, but not when it’s a child made to imitate adult artifice with no idea of the consequences. We see the same behavior with Shanti in The Jungle Book (1967), pretending to drop her pot as Mowgli is ‘lured’ by her into the Man Village. In the making-of documentary it is revealed that it was what Walt, who took active interest in the making of The Jungle Book before his death, required**. The Aristocats was made after his death but wasn’t too far from his influence, so I take it that this recurring female characteristic is Walt’s legacy. I was a fan of Disney well into my late teens, a large poster of The Little Mermaid (1989) adorning the wall of my room, but as an adult I couldn’t bear to watch it. What changed? Could it possibly the cult built around the Disney Princess, that virginal but seductive monument to girlhood that always seemed unattainable? It seems Disney in 1970 was oblivious to the second-wave feminist movement, still upholding the image of the nymphet. Now that we’ve been screaming it off the rooftops at every opportunity, hopefully they’ve got wind of it.

Which brings me to the second annoying aspect of the movie—Marie. As I watch Marie reinforce her weakness again and again, falling off an automobile, falling into the water, I feel it necessary to point out that her brothers are as the same level of maturity and motor-skill development, so it’s obvious that Marie is chosen to be the weakest link—an essential quality for the lady-in-training. I feel some relief as Marie stands her ground against her brothers when she becomes an object of their derision. Could it be, that in spite of the popular notion that little girls ought to primp, preen and be weak, Marie’s creators have managed to let a bit of spirit trickle into her? They fail again, for if the incorrigible little girl is loud and defensive, it is because she is spoilt, and the adorable Marie, being an aristocat, is definitely spoilt. I ponder a bit longer and look for some respite, but notice a conspicuous lack of female alley cats in that ode to Cathood, Everybody wants to be a Cat. In the real world, an ever-lovin’ female cat of the free world, living off scraps is a troublesome character to deal with. Taking anthropomorphism in all seriousness, she would probably be unkempt, pregnant, a prostitute, or all–not very good kiddy-toon material. If a romanticized feral female feline managed to make it through to the final edit, she would pose, and this I say only within popular notions of how females function, a threat to Duchess. I only consider this briefly as Duchess is regarded with a worshipful gaze yet again and there is no other female to disrupt the feline brotherhood.

Thomas is a wonderful father and the British geese add an entertaining subplot, but as you can see, I had issues with this film, perhaps a bit much? It is after all, a cartoon, an oldish one, reeking of the biases of a now dead dude whose work I can’t help but admire. I’ll justify this with a quote from Alice Sheldon (James Tiptree Jr.)***:

“Consider how odd it would be if all we knew about elephants had been written by elephants. Would we recognise one? What elephant author would describe — or perhaps even perceive — the features which are common to all elephants? We would find ourselves detecting these from indirect clues; for instance, elephant-naturalists would surely tell us that all other animals suffer from noselessness, which obliges them to use their paws in an unnatural way. […] So when the human male describes his world he maps its distances from his unspoken natural center of reference, himself. He calls a swamp “impenetrable,” a dog “loyal” and a woman “short.””

*I’ve deliberately left out the racist stereotyping in The Aristocats because it’s already been addressed in several reviews.

** But the general opinion is that it was tastefully done, so it’s a non-issue.

*** Stolen from here

Rhea got to see a lot of movies as a kid because her family members were obsessive movie-watchers. She frequently finds herself in a bind between her love for art and her feminist conscience. Meanwhile she is trying to be a better writer and artist and you can find her at http://rheadaniel.blogspot.com/

Do you think that sometime, you could do a week or month feature dedicated to posts pertaining to female animal characters in movies, cartoons, anime, and TV shows?

It’s depressing that there are so few female main protagonists and very few female animal main protagonists.

I can only think of a few.

1) Ginger the hen from Chicken Run (animated movie)

2) Mrs. Brisby the field mouse from The Secret of NIMH (animated movie based on children’s book)

3) Digger the wombat from Digger (web comic)

4) Chi the kitten from Chi’s Sweet Home (anime and manga)

There a few female alley cats in kids and family friendly cartoons and animated movies. The most notable examples of female stray cat characters in are Rita the gray and white cat from Animaniacs who is partnered with the stray dog named Runt, and Mittens the black and white tuxedo cat from Bolt who is partnered with the titular dog and a hamster named Rhino.