This is a guest post by Cynthia Arrieu-King.

SPOILER ALERT

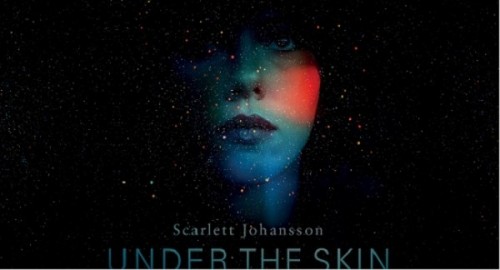

Scarlett Johansson herself says the movie Under the Skin is about an “it” becoming a “her”. Not a she: subjective, but a her: objective. This is the key dynamic character shift in the film, so that you’d think this film would embody a cultural critique of how women are treated, or at least, the idea of human predation. Because the “it” is a predatory drone and becomes a “her”, it first discovers slowly and sadly the immense vulnerability and mundanity of being a human person and then of being a human woman. The attractiveness of the Johansson human body (the thing for which she was singled out) ends up completely working against the alien. Its alien culture didn’t fully understand the position it was putting “it” in by putting “it” in a female body, and the amount of thinking we can see on the alien’s face as it is preying on people amounts to what we get from watching a spider on a web. Sometimes it’s the glass of water that does in an alien (Signs); sometimes it’s Johansson’s face and body.

In the first minutes, I didn’t think of a femme fatale; I thought Johansson was acting out some revenge fantasy–the abducted woman with the very deadpan comic twist: men don’t have to be abducted by force or tripped up by a woman’s doubt of her own instinct for being in danger; you can just promise them a one-night-stand with a lost English woman who looks like Johansson, and they’ll conveniently take their clothes off. That seems like the wink from the director, past the affectless alien, to us. Except the movie has a hard time offering up meaning from the gross amount of predation foisted on men—though it sure keeps showing their demises to us, over and over again.

What do you do with the insinuation that feminine wiles are basically manipulation? Or that men are so overwhelmed they can’t pick up on the fact that her questions are faintly pushy and one-track? Honestly, if I saw a gorgeous man on a beach, and he kept asking, “What are you doing here/are you alone/what country are you from?” I’d be taking ten steps back, turning, and walking away quickly. Which to his credit, is kind of what the surfer on the beach does when Johansson’s alien accosts him. The camera hangs on his face, taking in and registering the alien’s intrusiveness: she/it asks point blank what country he’s from. Viewers may worry, thinking: Are you gonna buy this, man? Are you really not noticing this is weird? He seems to feel baited, and the whole exchange is pushed aside for his altruism in wanting to help the drowning woman and dog. This is clearly a movie by a man: because if it were a movie by a woman. But we’re seeing a vulnerability in men we don’t often see on film. Considering the way the social criticism stays on a silent, not-very-deep level in this movie, backed up mostly by silence and blackness to fill in the gaps not covered in the story-writing meetings, I’ll take this one chance to see the tables get turned and go horribly wrong.

It’s hard to say what exactly is the trigger for the alien that makes her understand humans as something other than a meat parade. Is it mundane night life, malls, and people walking on the street? The alien’s modus operandi is a blend of “hunter” as well as tedious, dutiful, and atonal. I did not think she developed feelings or pity for humans. Her project is tedious to her. Is she really having a revelation about people? Or is this actually about sentience? Is she discovering the little bugs (humans) she’s picking off are values-driven?

Under the Skin seems more focused on the dreadfulness of being in another body, constantly amongst people who will want to kill her if they discover what she is. This isn’t, however, to say the movie is about Otherness in the way speculative fiction critiques and instructs on Otherness. It’s more about the weariness of being. Of being any being. Her work is so repetitive that I almost got enraged that it was still happening narratively, much less to these poor dudes. There’s no clue of how or when it could end. This can be read as rigor of repetition or, perhaps, as art for art’s sake.

Then comes the turning point, but it’s so crazily silent that it takes the length of this very long shot to understand what’s happened. The overpowering substance of the shot is that she looks out a window or into a glass tank and we see her face move from darkness into half-light. The beauty of this is its eyes go from an examination of the human as Other to self-regard pretty seamlessly. When the eyes dip into the light, the shot really communicates reticence and an inability to accept this gaze, this human face, these eyes. Does it look gruesome to itself? Maybe it loves this face? Is it creeped out? We don’t know whether or not sympathy is in the emotional currency on the alien’s planet, but we see something blows the alien’s mind. As a result, she releases the guy with neurofibromatosis (Adam Pearson) that we rolled our eyes to see going into her trap.

Why compassion for him and not the baby? She has remorse. Because she relates to alienation? Because of job burnout?

It’s worth saying a few words here about the cinematography and the setting of Scotland. In an overwhelming number of shots, the lighting is so dim you almost don’t know what you’re looking at, and there’s neon and noise and gold and graphics. This is a nod toward Jordan Chenoweth (cinematographer for Blade Runner) from DP Daniel Landin. The alien repeatedly echoes Rachel from Blade Runner in the use of eyelights—an almost totally dark face except for eyelights and the lighting of the lower third of her face. Why are we echoing Rachel here? Because Rachel’s humanity was tested through her eyes. She’d thought she was human but actually wasn’t. Here, Johansson’s alien ascertains something through an examination of her own eyes, thinks she’s not human, but, as the symmetry of this subtext goes, is about to find out she feels just like one.

Once out of the comfortable workplace of her van, Johansson’s alien is trying to stop with the predation. Except her kind didn’t study women enough to understand that just by walking alone on a road, she’s vulnerable. Here comes symbolic and literal fog on the road. She cannot see where she’s going now that she’s acquiring a conscience. She walks through the fog until she’s just passed it. This whiteness counters the blackness attached to everything the aliens do as day-to-day business. She rides a bus, now alone, and looks utterly freaked out like a woman who is trying to get out of a traumatic domestic situation. Except, it’s the situation she was sent here to embody that she’s trying to leave. She would prefer something more domestic, it seems, as she keeps going into houses—first a man’s and then a shelter in some woods.

There’s so much to say about the most retold, re-cast tale about predation in Western culture (Little Red Riding Hood) regrouping itself into some horrifyingly corrupted archetypes here in the last fourth of the movie. The book on which this horror movie is based is a piece of Michel Faber’s Dutch/Scottish horror. Little Red Riding Hood originated from a group of sexual assault warnings that filtered through the French countryside in the 17th century. Don’t let yourself be tracked. Don’t accept people on appearances (shey could be a wolf with your grandmother in its stomach). A wolf in grandmother’s clothes. And here after an interlude of almost-happiness in which Johansson’s alien-woman checks out her body in a mirror and ventures to have consensual sex, realizes what’s between her legs, she runs out into a forest where she shouldn’t be, where she has little idea how dangerous it is, and she’s warned to follow a trail by a woodsman, who ends up being the wolf.

The woodsman hits on her just the way she hit on men for the first half of the movie. What happens next is even harder to process, because in the end, isn’t she the wolf trapped in a woman’s body?

She pays for the underestimation, but the woodsman also pays for his underestimation with a terrible surprise for his rape-impulse. But wait a minute. After all the totally lamb-like men she’s picked up and stowed in her death lake, she’s out in a forest and the ONE MAN in the WHOLE FOREST that she runs into not only hits on her while trying to give her directions, but goes to find her so he can molest her, which then turns into him chasing her in the woods to straight up rape her.

Why is this piece of crap woodsman the last human she encounters on earth? Oh that’s right, we’re re-inscribing the message we apparently don’t get enough of: lone women who aren’t protected will be raped and killed. If you’re a wolf in woman’s clothing, good luck preserving your wily alien-wolf self because this near criminally insane woodsman will immolate you for being the uncanny. What did she do to become a predator magnet instead of the predator? She started feeling stuff. She gave up her predatory sex-kitten game. She tried to back up and see how she could possibly fit in and try to consider the essence of what she was doing. And so she ends up in a fate reserved for the more spectacular pieces of murdered women porn regularly paraded between 8-11 pm every night of the year on network television in both magazine and crime shows. Back to an object save the second moment of self-regard she has when she looks on her own Johansson face as a mask in her lap. It’s the one moment that makes this ending uncanny, and I would say, ultimately about being a human.

If you hear that people hate this movie, this re-inscription of feminine expendability and excoriation is probably why. There are too many too many loose ends and surface-like implications. People probably hate what happens to the baby: I think that’s when women walked out of the movie. The fact that men regularly walked out of screenings (because of the erect penises on the victimized men) is a whole other essay for a whole different internet venue and I want to read that essay a.s.a.p.

When Johansson’s corpse is burning up into the sky, the black smoke mingles with snow that flakes down to obliterate the literal camera lens. The fog comes back. And that male body-snatching alien looks off a cliff with his back to us, seeing or not seeing this black smoke, trying to find a sign in the confounding mist. He is not unlike a Romantic hero mystified who constantly feels alienated from Nature–a more tableaux version of what Johansson’s alien, in her last look upon her human face, must have felt.

See also at Bitch Flicks: Under the Skin of the Femme Fatale by Ren Jender

Cynthia Arrieu-King teaches literature and creative writing at Stockton College in New Jersey and has two published volumes of poetry. She has taught about 17 sections of freshman composition in which plagiarism was covered thoroughly, so beware internet magazines with sticky fingers. cynthiaarrieuking.blogspot.com.

I really needed this other review. I haven’t seen the movie yet, but I heard of it and I was really interested in seeing it… then I read the first article about it that was published here, then I got curious and read the book, and then your opinion confirmed me that the director has ruined the oportunity of actually adapting to the screen a book that has really interesting views on otherness and on the female condition, among other themes. What a pitty.

True. I think the movie is worth seeing on the level of a spectacle: we all sat there with our jaws hanging open, and I did detect in the middle something about the idea of otherness and femaleness, even “passing”. What the writer/director must have said in a meeting to change this all!

B^7 interesting only in it’s futility…. Loved it.