|

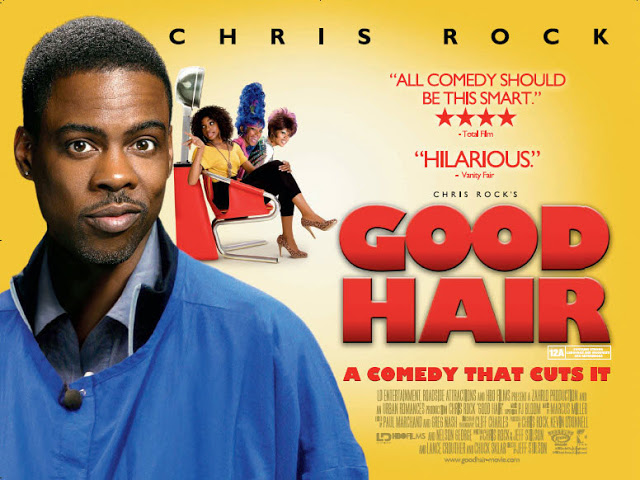

| An advertisement for Good Hair. |

Written by Janyce Denise Glasper

“Why should you get a perm?” asks Chris Rock, narrator and co-writer of Good Hair, speaking to a little girl who has endured the burning sensations of relaxers–“the nap antidote” and/or “creamy crack” since age three.

“Because you’re supposed to,” she replies.

Good Hair.

It has been stimulated since birth that European straightness is a coveted desire for its sleekness, bounce, and venerable marriage to a fine toothed comb. In Rock’s documentary that often seems more mockumentary dives into why this is the way of the world for African American women and how men must come to terms with this high cost of hair shame.

I remembered my first perm at age seven. It hurt like the devil. I didn’t get it because I wanted to. I was bullied into it- girls my own age hated my lovely braids coated in Vaseline sheen. So I hated them too and begged my mom for that perm, for that beautiful acceptance. I thought the pain was worth it. But often I regret being brainwashed early and wondered who influenced those same girls to get their heads “straightened.”

Good Hair reveals African American women allowing their children to endure unbearable excruciation at such an elemental age and it is horrendous, especially with “it’s hard to comb” being a prime excuse. We’re not raised to treat natural hair properly. As witnessed in scenes at Dudley School of Beauty- only the science of perming and hot comb techniques are taught. Is it any wonder why parents consider relaxers to be an “easy way out?” It’s an ignorance issue that a rare few want to unlearn.

When I went natural, many African American stylists didn’t want to do my heaping head of feral strands. Often I heard, “I cannot do that!” or “I will only do it if she put a relaxer on that head!” Always spoken with nasty disdain and cruelty. These comments (there are some unmentioned Rated R kinds) built negative self reflection for years.

|

| A six-year-old girl gets her second perm in Good Hair as Chris Rock watches. |

When Rock enters hair salons, hairstylists talk about nappy roots like it’s the ugliest catastrophe known to man, while applying burning white “elixir” from root to end to their clients. It strikes an emotional nerve. Those bullying days come back at full force at each wince and laughter from women spending so much time and money burying the truth.

A good friend once told me, “I don’t know why they make fun of your kind of hair when they’re hiding the same thing.”

It has been so heavily ingrained in African American society, in our culture, that all elements of black don’t necessarily equate to beauty and that some elements must be bought. In this instance, hair flown in overseas is much more valuable than attempting to honor and appreciate kinky curled existence.

Rock is also gearing up for a behind-the-scenes hair competition and funnily enough, every stylist feels threatened by Jason, a Caucasian man considered to be the “Rosa Parks” (adding insult to injury) of the contest because he knows African American hair so well. This seems to be the metaphor, the pink elephant in the room that African American competitors “fear” him.

Dr. Melayne Maclin, an expert dermatologist speaks out against the negative factors attributed to relaxers- its harsh, unreadable chemicals and brutal realities set upon little girls. Yet Dudley thrives on this exploitation, being one of the few African American owned hair businesses marketing to ironed out ideology. Strangely enough, in this billion dollar industry, Caucasians make more off African American’s insecurities with Asians being second. How odd is that? It’s as though hair has ultimately become another chain, another barrier and this time, no one is marching around with signs and chanting, “we shall overcome.” A perm is a normal rite of passage- straight hair is victor and nappy roots are a curse.

|

| Her definition of good hair- “something that looks relaxed and nice.” |

Rock laughs with them all at the perm’s downside- the murdering scalp sensation, reddened ears, ugly patches where skin has been scorched off. But these women beam proudly, acknowledging worth like a soldier’s battle scars.

After I gave a presentation on black hair’s manifestations in art and design history class, someone asked me, “does black people hair really grow out like that? I’m so used to it being straight like ours.”

The documentary is a cruel implication that only one type of hair is acceptable and defined as “good.”

Rock didn’t find enough women who aren’t being imprisoned by relaxed and European culture. Alopecia survivor, Sheila Bridges bravely chooses not to wear wigs and showcases her bald head beauty proudly. “I never want to feel like I was hiding something,” she speaks articulately.

|

| Tracie Thoms discussing why she loves being natural. |

Actress Tracie Thoms appeared to be one of the few celebrity champions. She spoke up on celebrating forbidden other side. She believes that a freedom comes from natural beauty, embracing God given gift while the other Hollywood women were bluntly bragging about their expensive weaves like it gave them confidence and prestige. Thoms, however, was an anomaly. She raises an important question- “to keep my hair at the same texture as it grows out of head is looked at as revolutionary- why is that?”

Whether shaven bald, out free in afrocentric glory, braided, twisted or locc’ed, this “I’m not stressed” hair movement has been gradually rising for years. With entrepreneur women like Lisa Price, owner of natural hair line, Carol’s Daughter, things are shaping up into a new form of Angela Davis/Pam Grier inspired reformation thanks to hair bloggers and urgent call for earthly, less chemical ingredients in haircare.

“If my daughters wanted to wear weave one day, I had to see where it came from,” defeated Rock says, giving up on the idea that his children would actually want to remain natural, continuing to instead expose more vanity of oppressed black women and their disgrace.

He travels as far as to India where women, even crying babies are sacrificed in head shaving rituals called Tonsures- an exchanging of hair for God’s blessings. Sometimes Indian women are robbed of hair in sleep just to appease black market greediness- hair is such a valuable commodity that it is perceived to be wealthier than gold. Clear packages of long, glossy Indian roots are wrapped up like bundles of cocaine and shipped to people who probably know little about the history of this hair, of the person who was shaved bald intentionally or otherwise.

Rock tries, but with no success in trying to sell African American haired wigs. It’s both comical and sad, worsening when an African American woman working at an Asian hair store says, “black people don’t wear their hair nappy anymore.” Her agreeable boss with hands widening (wild “scary” afro), “they don’t want to look like Africa.” He points at the Indian hair and waves down his hands. “They want to wear their hair straight. It’s more sexy, more natural.”

But it is not natural. It is a preconceived, very contrived notion stimulating from white men’s rule that whiteness embodies beauty and thick, coarse, matted naps opposes that law.

And where is the sexiness when it becomes a production, a choreography in a relationship?

Despite men joking and women testifying, weave does get in the way of real life- financially, physically, and emotionally. It is an expensive venture and some women actually do attend to themselves more than paying mortgage and car notes on time. Touching is a natural occurrence in intimacy and to have a law where hair isn’t a part of deal sounds quite preposterous. As these men showcase scandalous stories and speaking of preferring other nationalities, African American women are appearing shallower and less desirable than ever.

But alas this documentary is written by three men and told through the eyes of a man.

|

| Chris Rock talking to scandalously clad women about hair. |

It is difficult to watch because this isn’t a one hundred percent honest depiction. These women loving their weaved safety nets aren’t very likeable or representational of a whole culture. Hair is a sense of pride, power, and creativity- as seen in the hair/ fashion show taking much of Rock’s attention. In the natural hair world, severely lacking here, there is no hiding, no masquerades.

“Hair is a woman’s glory,” says Maya Angelou who got her first relaxer at seventy years old. She couldn’t be anymore right.

Rock may close with the fluffy, “it’s what’s inside their heads that matters most” philosophy, but it is a contradiction- what positively reflects on the outside should match what’s within. If there were a sequel to Good Hair seen through the scopes of an admirable African American woman who knows fierce, independent trendsetters worthy of worship and inspiration, most of the men featured in Rock’s production will wish they never defamed her character.

5 thoughts on “Good Hair From Root To End: Why Is Nappiness Still Considered A Sin?”

Comments are closed.