This guest post by Colleen Lutz Clemens appears as part of our theme week on Rape Revenge Fantasies.

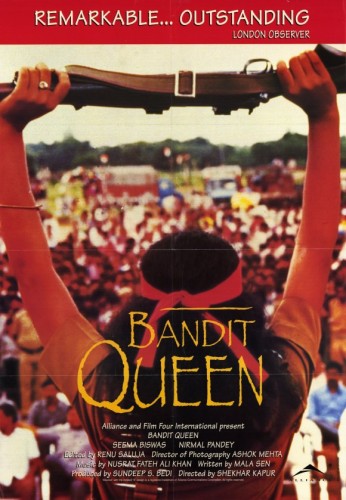

When reading articles about the rape revenge genre, one sees cited I Spit On Your Grave, Teeth and other western films. But I would like to put forth that Shekhar Kapur’s 1994 film Bandit Queen should be considered a rape revenge film, even if the film that is supposedly putting forth the “truth” exploits the rape of the main character Phoolan Devi, an Indian gang leader who was murdered in 2001, to drive the plot of the “biopic.”

Phoolan Devi herself did not authorize the making of the film depicting her life and filed a lawsuit against the filmmakers. In a 1999 interview with AkasaMedia, she bemoaned the fact that more people talked about the mythology of Phoolan Devi than of Phoolan herself: “It’s unfortunate that they don’t talk much about me, they don’t write much about me, the real Phoolan Devi. Of course the movie is also a part of the story of my life, but it’s not the real thing. I wish they could have done it more realistically. I also wonder why they focus so much on the movie, instead of on the real person.” When explaining why she filed the lawsuit, she explained, “The case is over, I’ve withdrawn it. What I wanted was that, in India, they shouldn’t show four scenes of the movie. One was the rape scene. They should not show that, because people feel very disturbed about it–society can’t take it.” Devi herself did not want the rape scene shown. This scene (and other shorter scenes of brutality against the character of Phoolan) works to transform the film from a biopic to a rape-revenge film; the protagonist’s actions are motivated by a desire to make her rapists suffer, leading to the climax of the film.

Halfway through the film, Phoolan is captured, thrown on a boat, and taken to an enemy’s hideout where her bloodied body is tossed into an outbuilding. The first man enters the building (1:14) and the viewer is on the floor with Phoolan as she watches him approach. A beam splitting the screen makes us feel trapped with her. Her feet are untied so her legs can be splayed. Her cries continue as the other men come to watch her being raped. The camera lingers on rusty debris between the rapists’ entrances and exits. The light softens on her battered face while the rest of the room is dark and dusty.

Man after man enters the building during the three-minute scene pierced by her cries and their grunts. The audience is to assume that the assaults last for another three days until the bloodied, naked Phoolan is forced to walk in front of the village, arriving at the well where she must fill the urn thrown at her feet.

Her main perpetrator, Thakur Shri Ram, grabs her by the hair and drags her through the square while young girls watch and receive the message that no woman should ever dare to desire a position of power in a gang.

From this point in the film, Phoolan becomes larger than life. As her body heals, her desire for revenge grows. She cultivates a new gang. She collects weapons. She earns the moniker of the hero, “The Bandit Queen.” When she arrives at a wedding attended by Shri Ram (1:37), she exacts her revenge. She has her gang line the men up so she can harass and beat them.

The sound of a girl child’s screaming permeates the scene. As Phoolan shoots the men, the camera cuts to the naked child wandering the scene. She and Phoolan are the only females present. The audience sees Phoolan’s intense desire for revenge in her eyes as she punches and kicks the men who raped her or stood by as she was raped. As the child screams, Phoolan’s gang shoots the men dressed in white, pulverizing them into bloody mounds. Gunshots are juxtaposed with the toddler’s cries. The camera follows Phoolan’s eyes as she watches the men being executed. The naked child stands at the well, an empty bucket behind her, forcing the viewer to connect the screams of Phoolan to the screams of the child, linking this scene to Phoolan’s rape earlier in the film. The scene ends as the child walks alone across puddles of blood.

Again, Phoolan Devi herself did not want the rape scene in the film. Yet the final rape scene becomes the defining moment in the film, the turning point when the character Phoolan begins her trajectory to becoming the legendary Bandit Queen. In the film’s depiction of Phoolan, she acts out of revenge and also helps other lower caste people along the way. Her motivating desire is to gun down those who raped her, who demeaned her, who humiliated her. Arundhati Roy, an Indian writer and activist, wrote a scathing piece in which she claims those responsible for the film silenced their subject and disallowed Devi from even having a claim to her own life story. In “The Great Indian Rape Trick,” she says the film should be entitled Phoolan Devi’s Rape and Abject Humiliation: The True half-Truth?, arguing that the “centerpiece” of the film—the rape scene—is exploitative and not “tasteful” as the critics have said. Mala Sen, the film’s screenwriter, told The Independent in a reply that Phoolan did give consent for the film and signed the contract willingly and argues that Roy herself is using Phoolan as a pawn in another ideological debate.

All of the debates leave me with the same questions: Why does Phoolan Devi need to be repeatedly raped in the film? Why does the film shift into the rape revenge genre instead of acting as the biopic that the filmmakers claimed it to be?

When considering female agents of violence in a film, there is a troublesome tendency that plays to the audience’s anxiety about a women disrupting the essentialist notion that women are naturally gentle and nurturing: the tendency to have the woman acting in response to sexual violence, that only after a woman is overpowered and assaulted can she find a place of violence in her. Once the naturalness of a woman is disrupted by an outside force—a (usually male) perpetrator—she is no longer required to be viewed as “womanly.”

Is it so “unnatural” to see a woman leading a violent gang that we require a monstrous reason to allow us to rationalize her existence? Would audiences be unable or unwilling to go along with the narrative if there weren’t some reason, some thing we could all point to and say “Aha! That is why she isn’t acting like a woman anymore. Because the thing that made her a woman was taken away from her,” as if a woman cannot have access to violence as a form of resistance?

I teach The Bandit Queen along with Teeth and ask students to consider both as rape revenge films. While the latter is a little easier for students to connect with contextually, they are able to see the former for what it is: a rape revenge film. While not a successful biopic, as a rape revenge film The Bandit Queen offers the audience a satisfying conclusion following the genre’s plot and character development. Phoolan finds agency in violence and is able to make those who wronged her regret their actions.

Colleen Lutz Clemens is assistant professor of non-Western literatures at Kutztown University. She blogs about gender issues and postcolonial theory and literature at http://kupoco.wordpress.

After watching movies such as the Bandit Queen, Teeth, and Kill Bill, I can’t help but agree with you when you point out that most of the time, if not all of the time, women have to be assaulted or raped in order for them to be violent or take some kind of revenge. For example, in Kill Bill, there was a rape scene, however I feel like it did not have to be added in the film at all. The bride had so many different things to be revengeful for, her husband was killed, her baby was killed, and I feel as though the movie made it look like she became violent only because of the rape. Also, another example is the movie Teeth, which I could barely watch by the way. It showed its audience that a nice young girl could become violent…but only if she was raped or assaulted first. You said, “Once the naturalness of a woman is disrupted by an outside force-a (usually male) perpetrator- she is no longer required to be viewed as “womanly.” I feel as though that is definitely the case in this film because once Dawn O’Keefe is raped, the movie almost portrays her as a monster. She has lost all her “womaness” and has become something completely different and “unnatural,” just as Phoolan Devi does, when she becomes a gang leader because it couldn’t possibly be natural that a woman would be violent for any other reason other than being assaulted and humiliated.

In this post, it was also mentioned that Phoolan Devi did not want a rape scene in the Bandit Queen, however, it became the driving force of the movie. Now, I don’t know much about Phoolan Devi other than what I have seen in this movie. However, I feel like she was probably fighting for more than just getting back at men who raped her. A biopic is supposed to be about a person’s life and I highly doubt that this is how she wanted her life to be portrayed. You even mentioned how Phoolan mentioned how this movie was not true to who she is. Being raped or assaulted affects a person in so many ways but it is not the only part of a person’s life story and it is in no way the only reason a person, or woman rather, could be violent. Why couldn’t she be violent in order to fight for what she believed in? Why are films continuously hurting women in order to give them a reason to fight back?In these films men are usually the reason women become violent. Men are usually the reason women fight back. Why can’t a woman just fight for what she believe in? Why does a woman have to be touched by the act of a man in order to become violent? Why can’t it just be her own, not only because she’s a woman but simply because she’s a human being?

I’d have to agree with you; despite its classification as a biopic, Bandit Queen certainly does fit within the genre of rape revenge, which takes away from the true story of our protagonist. The amount of focus that this movie has on the rape of Phoolan Devi draws our attention away from the fact that she—the real Phoolan Devi—was lashing out against a broken and unjust system, which includes, but is not limited to, the men who raped her. In other words, the plot of the biopic is lacking.

Although I appreciate watching Phoolan Devi rise up from oppression to become the highly influential leader of a gang that fights against the cruel domination of the Thakurs, the movie repeatedly reminds us that she’s doing all of this because she is seeking revenge from the men who raped her. As your post points out, though, there was much more behind Phoolan Devi’s story than this. You mention that Phoolan Devi disliked the fact that she was not realistically portrayed in this movie, saying that she “bemoaned the fact that more people talked about the mythology of Phoolan Devi than of Phoolan herself” (Clemens). This leads me to believe that Phoolan Devi’s story is so much more complex than the rape revenge plot that this film essentially offers us. It is not my intention to downplay the horrific nature of Phoolan Devi’s rape, nor is to deny the amount of impact that such a terrible experience would have had on her life; I am only saying that I believe Phoolan Devi was fighting against so much more than that—she was fighting against a system that perpetuated a culture of rape, abuse, neglect, inequality, and injustice.

The movie briefly captures this toward the end of the film whenever Phoolan Devi turns herself in to the ‘authorities’ and the crowd begins to cheer her name. As the film mentions, her terms of surrender included protection for the people of India, as well as their right to land, security, and an education. Clearly her actions were driven by her desire to improve the quality of life for a country of underserved citizens, not just to bring justice to the men who had raped her. However, by focusing so much on the sexual abuse that Phoolan Devi endured, the movie skews the overall purpose and intent of (the real) Phoolan Devi’s actions. I believe that my thoughts here are in line with what you have to say about Bandit Queen:

[These] scenes of brutality against the character of Phoolan…[work] to

transform the film from a biopic to a rape-revenge film; the protagonist’s

actions are motivated by a desire to make her rapists suffer, leading to the

climax of the film. (Clemens)

As you mention in your post, by presenting Phoolan Devi’s story in this manner, viewers are able to justify her “unnatural” and ‘unwomanly’ actions through the fact that she was raped. I agree with you that this downplays the idea that women are capable of violence—unless, of course, something happens to them that leaves them with no other choice than to avenge themselves. The movie is attempting to justify Phoolan Devi’s actions for its audiences by reminding us that this woman has been raped, therefore, she has a right to commit these crimes. Is this really necessary? Shouldn’t the factual story of Phoolan Devi’s life be enough to justify why she to became a vigilante, or more specifically, the leader of a gang? Does the movie need to repeatedly capture for us the rape that Phoolan Devi was brutally forced to endure in order to explain to us why she resorted to violence? You pose similar questions in your post, and I wholeheartedly agree with you. No, it doesn’t need to portray her story in the light of a rape revenge film. By doing this, it only takes away from the agency of Phoolan Devi, the woman who disrupted the hegemony of an oppressive country.

Although I can understand why this would be seen as a rape revenge movie, there is an underlying current that is much deeper than the overall assumption of attacking or killing the men who violated Phoolan repeatedly. The reason I liked this movie was because in spite of her circumstances, Phoolan rose above what happened to her and fought to bring justice to those in a lower caste. I cried several times during this movie seeing what she had to go through and especially when it showed the little girl by the well.

It sickens me the way women are treated as inferior, lower class citizens because of gender. It pained me to see men of power and wealth abuse their status to prove superiority. The scene with the little girl at the well hurt the most. All I could think was, didn’t anyone care if she fell in it? To see tomorrow’s future tossed aside as if worth nothing and because she was a girl truly disturbs me even though it is considered the ‘norm’ in that culture. I can fully see Dr. Clemens point though about being exposed and vulnerable when Phoolan was forced to collect water at the well after she was brutally raped. How does one recover from such humiliation?

Showing another woman starkly naked to portray the gruesome past that one woman gone through, does not in any way justifies the purportedly attempt to create awareness of protecting or honoring the dignity of woman that these so called film makers claim. The movie may have presented Phoolan Devi’s bravery and courage (not really though) but it failed to respect Seema Biswas dignity as a woman and a human.

I agree with you that this movie, Bandit Queen, falls more under the genre of rape revenge rather then a biopic. The movies main focus is the multiple rapes that Phoolan Devi experiences throughout the course of her life and how she responds to these rapes with violence. One of the longest and more painful scenes to watch in the film is Phoolan getting gang raped and then humiliated by her rapists. I agree that this scene is the turning point in the film, which leads to her becoming this powerful and inspirational figure. Not only does she seek revenge on those who raped her but as seen in other rape revenge movies, like Teeth and Monster, she takes on a vigilante role and declares that she will come after all men who take advantage of children. I don’t like how the movie makes it seem like she could only tap into this strength because she survived being raped. This post discusses that Phoolan’s response to being raped makes it seem like her only motivation is to get revenge on those that wronged her. I agree that this is how that movie portrays her actions. However in reality not only was she getting revenge on her rapists but she was fighting for lower class people and women like her to be treated with respect as well. This message gets lost because the rape scene is the focus of the movie instead of her efforts to start a change in society with the use of violence.

I agree that the rape scenes in this movie are used as a way to justify the violence that Phoolan Devi enacts on her rapist. As was discussed in this post it is easier for an audience to accept a woman enacting violence if they are doing it as a response to a violent act. I agree that the comfort this gives the audience is one of the reasons that the rape scenes are one of the main focus points of the movie. This need to justify a woman being violent is part of the reason why the rape revenge genre exists. The need of the audience to justify women’s use of violence increases the need for women to have a reason to be violent in media and one of the most excepted reasons is being sexually assaulted or raped. It is only when women have an excepted reason for violence that the audience can comprehend them enacting violence.

Phoolan Devi’s character is one of immense persistence. I am appalled that in wanting to show a story of pure womanly power the writers of this film did the one thing that they were probably fighting against in making this, they went over her head. As is mentioned the filmmakers did not even allow Devi the privilege of claiming her life story going against what they are trying to portray in the movie; a woman who overcomes so much. I agree that the rape ideal in the movie was over played, however I disagree that the directors made the reason Devi became violent because of the fact that she was raped many times. Devi, in the movie, was portrayed in the beginning as already being assertive in her own right, even before any men had a hold on her. I think this might have been what the directors were trying to get at. What they failed to do however was to attribute her violence to a genuine aggressive trait in her as opposed to making her rape the rationalizing factor.

Playing this movie out as a rape revenge takes away from Devi’s reasoning for being a gang leader. Yes she might have been raped but the excessive portrayal of her rapes as a means to justify her actions is out of line. This film reminds me a lot of Teeth and Monster. Dawn is different to Devi in that she does play out the narrative of the damsel in distress. But both women are forced out of their general character by another man taking advantage of them, not because they want to be. Or at least this is how it is shown. In Monster Aileen is different in that she does not play up the Damsel in Distress trope but still she must be taken advantage of to be angry enough to kill the men she does. The audience, in the scene where Devi kills the men standing in a line while the baby cries, is a straight unconscious effort to have the audience associate her killing with her raping. In Teeth Dawn is portrayed as so innocent that her anger could only come from the men she is dealing with. Women are never in charge of their own anger and if we are there must be a problem with us. Men are consistently portrayed as hero’s to others for no reason other than that they have the strength to be. Women are providers and to stand back and have a woman save a man, or herself for that matter is a monstrosity to the general society.

Reading this article we learn of the “character” Phoolan Devi, “an Indian gang leader who was murdered in 2001” (btchflcks.com). Bandit Queen is her biopic. I put quotes around the word “character” because the fact that Phoolan in the biopic is different from Phoolan in reality is something the article touches upon. Phoolan herself felt she was being set up as a mythological hero rather than a person. I feel Phoolan being seen as a person is important because if one becomes unattainable, then others might not feel as if they can follow in their footsteps. They’ll feel inadequate. This high status also operates in the line of exploitation, as the rape scene, something the article questions if necessary, is supposed to act as the climax of the film, as well as the character and her descent into revenge. Phoolan, herself, thinks otherwise. That rape was not her pinnacle awakening, it was a stepping stone to how she became the person she was. It felt as if cinema was saying women couldn’t become something great if they aren’t put to violence first.

What is female agency? Can a woman, or person identifying as one, have it? Or does it have to come from an outside source? These questions plague the article because the biopic says yes, but only if something happens first. That violence or experience is what allows the woman to shed her femininity and become the leader she can be – something mostly thought to be a male occupation. The article even states, “Is it so ‘unnatural’ to see a woman leading a violent gang that we require a monstrous reason to rationalize her existence” (btchflcks.com). Requirements are set up to control and package people into little boxes, and if people continue to be packed and repacked in different ways, it’s going to be hard to fight back. If gender is so fluid, being a man or a woman shouldn’t matter in the context of revenge or violence or agency, but it does. Painfully so.

Something that echoes the sentiments of the film is, unexpectedly, the book Gone Girl by Gillian Flynn. Like Phoolan, i.e. the character, Amy Dunne results in violence, because she believes violence has been enacted on her, giving her sentiment to do violence. However, their violence is of two different kinds. With Phoolan it was physical to her body and with Amy it was mental, or societal if one really wants to get dirty. I am not going to take away the mental distress that rape can have on a person, but something I believe the film was trying to get across is the idea of physical violence was needed to make her snap. With Amy, she knew what she was doing to her husband, Nick. She knew and she got tired because she wanted him to be the way he wanted her to be. Perfect. The Cool Girl. This exhaustion of not getting back what she was giving, made Amy, in a way, snap, in order to wake Nick up to his “real” reality. Both characters, Phoolan and Amy, experience violence differently, but their turn to violence and how the audience perceives both is very different. With Phoolan, it is more of hero, possibly an anti-hero in the fact she kills, but a hero in the sense of righting a wrong, of her and women everywhere. With Amy she is seen as evil, because she makes people aware of the dangers of illusion and society, enacting violence because she feels she can. So audiences fear her more because they created her and their experiment went wrong.

Rape is a form of dominance and showing who’s in charge and they play in power dynamics and the dismissing of agency. In the case of the Bandit Queen, disregarding Phoolan’s wishes to not include the rape scene parades the overall lack of respect for both the individual and women in general. Aside from a lack of empathy and common decency, a more primitive explanation of creativity also plays a part in finding different and refreshing ways to drive a story. The rape revenge plot is dry and old and disrespectful. If feels overused as the propelling point for women to commit violence. Rape scenes are exploitative in real life and media but media is a reflection of prevailing mentalities of our culture which indicates what and who we value in our culture.

I don’t think there is anything wrong with rape revenge films but I do think there needs to be a balance of different motivators for women of violence in our media. Tammy Oler addresses this in her article “The Brave Ones” saying that the “films are doing more complicated cultural work.” She continues to say that they culminate violence against women while simultaneously giving the illusion of “female power and recrimination that is second to none in cinema.” The role of rape revenge films provides women with an outlet of illusion to witness a redefining of the traditional character women often play. They allow women to be violent and enact vengeance, even if it is by the provocation of men.