Written by staff writer Ren Jender as part of our theme week on Black Families.

When I was a kid in the ’70s, Happy Days, which took place in ’50s, was one of the most popular shows on TV; my sixth-grade teacher showed daytime reruns to the entire class during lunch as a method of crowd control. My mother, who had grown up during the 1940s and ’50s told me, “The ’50s weren’t really like that.” I think of her whenever I see films (like the execrable Inherent Vice) that take place during the time I grew up. The differences between the ’70s and now are deeper than just a matter of hairstyles, fashion, and phones.

We can see that difference clearly, and beautifully, in Black writer-director Charles Burnett’s haunting first film, Killer of Sheep, shot on weekends in the late ’70s in the Watts section of Los Angeles (the cinematography, which features painterly black and white images, is also by Burnett). More than once we see kids (with no adults around; most kids in those days–including those in the suburban, mostly white neighborhoods where I grew up–were “free-range kids”) playing in groups in dusty, hazardous-looking outdoor spaces which reminded me of the bombed out ruins the London boys of the WWII-set Hope and Glory play in, right down to one boy using a tool to make a dangerous item go “bang”–in Glory, it’s a hammer and nail to a stray bullet. In Sheep, one young boy uses a plumber’s wrench to bang at the strip for a toy cap gun to set off its small traces of explosive material. The ruins in London were because of enemy bombing. In Watts they might have been a vestige of riots in the 1960s or just a sign of many cities’ general neglect of their Black neighborhoods. But the children do have the run of the place; the film captures an era before gun and police violence made the streets fatal for many of them. When one boy tells another he’s going home to get his BB gun, I couldn’t help thinking of 12-year-old Tamir Rice who, a few months ago, police shot and killed in a playground just for carrying the same item.

The neighborhood’s busted-up fences, dilapidated cars, and a garage with a big enough hole in the door that children slip easily in and out through it seem to have etched themselves into the careworn features of the title character, Stan (played by Henry Gayle Sanders, a familiar face from small and “guest-star” roles on ’70s and ’80s television). One woman tells him he’d be handsome if he smiled once in a while.

Stan works at a slaughterhouse (we see the animals first alive then killed, skinned and decapitated on the assembly line) and lives in a small one-story house (decades before the internet chic of “tiny houses“) with his wife and two children. We see that the family doesn’t have much, but like a lot of other low-income people, Stan points to others who are worse off. He tells an acquaintance, “Man, I ain’t poor. I give away things to the Salvation Army. You can’t give away nothing to the Salvation Army if you’re poor.”

Stan has to have a long discussion with a man and his array of family members to get a car motor for the amount of money he can afford. He and his friend painstakingly carry this heavy, unwieldy conglomeration of metal (the muscles in the arms and chests of the actors, when most people didn’t go to the gym, shows evidence of the hard, physical labor many Black men did for work at the time) down a couple of flights of stairs, resting more than once along the way and hoist it into the back of his friend’s pickup truck, which injures the friend’s finger. Stan asks, more than once, if they can push the motor all the way toward the cab but his friend says it will be fine where it is. When his friend starts driving the motor immediately falls into the street, sliding downhill a little. They both agree it’s ruined, so they drive away, leaving the motor where it fell.

Stan has a beautiful wife (Kaycee Moore who would later appear in Daughters of the Dust) who cares for and loves him, but she can’t make him forget his troubles. He dances with her to Dinah Washington singing “This Bitter Earth” (“What good is love/ Mmmmmmmm/ That no one shares”), but is too melancholy to have sex with her. She’s jealous as she watches him freely accept affection from their young daughter (Angela Burnett) in a way that he won’t with her. The audience understands that with the daughter the pressure’s off, but his wife cries as she watches the two of them.

Stan yells at his son (Jack Drummond) for being “country” when the son asks his Mom for money, specifically because he calls her “madea” (a form of address for mother figures Tyler Perry did not invent). The son then picks on other kids, including his younger sister. Stan’s (nameless) wife yells at the kids too, because of her own frustrations, both with Stan’s depression and the “friends” of his who stop by, like the ones who talk about killing someone they know and ask for his help. After he turns them down she goes off on them, shouting, “Wait just a minute you talk about being a man. Don’t you know there’s more to it than your fists?”

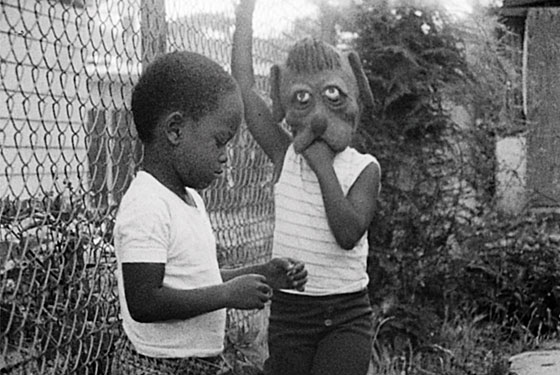

No director has captured as well as Burnett does here the dynamics of children (of any race) at play. Stan’s daughter, for no particular reason, wears a cartoon dog mask as she stands in the house and goes outside (the way one of my best friends when we were about her age used to wear a long, blonde wig). In one moment, among a group of boys, a pretend fight turns into real one in which someone gets hurt. Kids leap back and forth between two low buildings about six feet apart in a way parents (and directors) would never, ever let happen now. We see children try to advance in the pecking order and find themselves literally beaten down afterward. A young boy on a bike tells two older girls doing The Bump on a street to get out of his way, but the two girls and their friends gang up on him until he runs away, leaving his bike behind.

One of the scenes most evocative of the ’70s I knew features Stan’s daughter playing on a cluttered floor with her (white) baby doll as she sings along to Earth, Wind & Fire’s “Reasons” on the radio, making up her own nonsense lyrics to replace the more sexually suggestive ones of the song (as kids today do with hip-hop lyrics). Filmmakers so rarely just hold back and let us see how little girls play, especially when they are by themselves. And this scene with different music and maybe a different doll (for me it was Barbie or Dawn dolls) could have come from the lives of young girls through the ages.

As in real life, the film has neither a happy ending nor a tragic one. A day at the racetrack is derailed by a flat tire. Stan goes in for another shift at the slaughterhouse. We again see the living sheep and the assembly line. As we hear “This Bitter Earth” once more, I burst into tears.

[youtube_sc url=”https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-nXw-8MXhVE” iv_load_policy=”3″]

___________________________________________________

Ren Jender is a queer writer-performer/producer putting a film together. Her writing. besides appearing every week on Bitch Flicks, has also been published in The Toast, RH Reality Check, xoJane and the Feminist Wire. You can follow her on Twitter @renjender

2 thoughts on “‘Killer of Sheep’ A Slice of Life of Watts in the ’70s”

Comments are closed.