This is a guest post by Holly Rosen Fink.

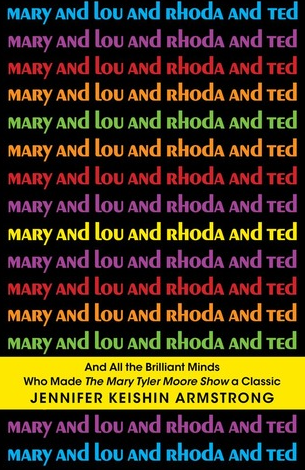

One of the greatest shots ever in the opening of a show has to be of Mary Tyler Moore tossing her hat into the air with the theme song “You’re Gonna Make it After All” in the background. The visual and audio combination is very telling of a time when women were breaking out of their shells in the 1970s. The show was ground-breakingly feminist in many ways – the two male producers hired a group of mainly female writers and took the show’s plot in daring directions every chance they got. I sat down with Jennifer Keishin Armstrong, the author of Mary and Lou and Rhoda and Ted: And all the Brilliant Minds Who Made The Mary Tyler Moore Show a Classic to find out how they did it.

How did The Mary Tyler Moore Show‘s producers get the scripts so right during a time of upheaval for women in American history?

JKA: They hired women, for starters. It’s a real testament to gender diversity, because they ended up being able to get the input of the female writers they hired, even as they hired plenty of experienced men who could write a killer script. This also allowed fairly inexperienced women who hadn’t gotten a shot before to get the skills and resume lines they needed to move up in the business. It made a huge ripple-effect difference in the industry in ways we probably can’t even begin to measure. That said, feminists at the time didn’t love the show — as with many groundbreaking shows, it was under tons of scrutiny as the only show of its kind. They hated Mary’s weaker moments and her propensity to call her boss “Mr. Grant” while others called him “Lou.” In the end, I think these chinks in Mary’s feminism made her a stronger character and a better ambassador. But it took the perspective of history to see her that way.

The Mary Tyler Moore Show show went on in 1970. All these years later, it’s still inspiring and influencing writers and characters on TV. Why is that?

JKA: I think it’s a writers’ show, to a large extent. It’s so character-driven, rather than just joke-driven. Writers respond to that and want to make their own shows that way whenever they can.

Originally, Mary Tyler Moore was meant to be divorced but the network refused. She still ended up single and working, which was a revolutionary story line in the 1970s. What was it like talking to the show’s creators about this period of the show’s history? Were they open about their experiences?

JKA: I am such a sucker for those stories of disgusting, blatant early sexism, and the Mad Men-type stuff! When the show started, things were very different than they were even a few years later — it was a time of very fast change in gender politics. When they were pitching the show, the one female executive who championed it was such an anomaly that they had no executive restroom for women. When she was on that floor, she just left her shoes outside the bathroom to let them know she was in there. And yes, the network folks had no interest in Mary being divorced. As one of the executives, Mike Dann, told me, he thought a divorcee would be “kind of a loose woman.” The fact that a few seasons in they could have references to Mary taking birth control and staying out all night on a date is a sign of quite rapid progress.

But they took risks when they could, writing divorce in later for Lou and a gay brother for Phyllis and Rhoda as a New York City Jew. Eventually, Mary was staying out all night and going on the Pill. How did the writers push these modern ideas through?

JKA: They were partially sneaky and partially lucky. A few years in, divorce seemed more palatable, and giving it to Lou instead of Mary certainly made a difference. It didn’t sully their sweet heroine. That said, All in the Family had since come on the air, which blew open a lot of previously closed doors in terms of subject matter. With both All in the Family and Mary doing well, the network was much less likely to mess with them. Network executives are only skittish when something isn’t raking in tons of cash. The gay brother storyline wasn’t originally part of the script; it was added when the actor playing him happened to be gay. But it was still possibly the most blatantly edgy the show ever got. The all-nighter and the Pill were couched in very subtle references that certainly a younger viewer would miss completely. Mary simply mentions offhand that she won’t forget to take her pill, which could, after all, be any kind of pill. And we know she stayed out all night only because we see her leave her apartment at night in an evening gown and return the next morning in the same dress. We never find out what really happened during those hours.

Most of the writers were women. Were they active in the feminist movement?

JKA: They were. I don’t remember any saying they weren’t, and for most of them, it was just an obvious and standard part of life at the time. They went to regular meetings and some of them engaged in at least small forms of activism. I don’t think they had time to be major players in the movement because they were too busy working!

Why did you spend so much time focusing on their lives (which I loved, by the way)?

JKA: It seems like the only interesting way to tell the story, to me. For my tastes, I prefer stories about people rather than just a bunch of geeky trivia about a show. I wanted to write something that goes beyond a fan encyclopedia. There’s a place for that kind of book, for sure — and I used them in my research! I wanted the book to reflect the show, and I think if the writers of The Mary Tyler Moore Show had to write the story of their show, this is the way they’d do it — by focusing on the characters.

Ethel Winant was the only female executive at the show’s start. There were so many men that she didn’t have her own toilet. How did she know the show would be such a huge success?

JKA: She certainly had well-honed instincts, and the show is evidence of her impeccable casting skill. But I think she also responded to the material itself. It makes sense that she would see the value in a show about a career woman, given that she was such a pioneer, and my interviews with her son backed that up.

How did Mary Tyler Moore change the face of TV and women’s roles in the TV industry?

JKA: Like any success, it spawned many attempts at re-creation, which meant lots more shows about women. Some of them stuck, like Maude and even Mary’s spinoff, Rhoda. It also produced several female writers who could go onto other things, kind-of spreading the show’s influence that way. They went on to write for many shows, create some shows, produce, and work as TV executives. They also inspired that entire generation of women who’s currently kicking things up a level, producing in and starring in their own shows.

Was the network supportive of their efforts?

JKA: At first, the network was skeptical. But success is the best way to get the network off your back, and by the end of the first season, the show could mostly do whatever it wanted.

At the time Mary Tyler Moore was on, All in the Family and Maude were developed. Did they compete with these shows?

JKA: They didn’t really. They were all on the same network — CBS was it at the time. So they were able to enjoy each other as colleagues quite a bit and just admire each other’s work. The Mary Tyler Moore guys — Jim Brooks and Ed. Weinberger and Dave Davis — would actually watch All in the Family together and marvel at its greatness. They certainly wanted to keep up their own standards to stay in step with Norman Lear’s shows, but they couldn’t ever compete directly with them.

Did the actresses realize they were feminists at the time? Did any of them stay involved with the movement post 1970s?

Val Harper identified as a feminist, and continues to, while the others didn’t as much. Val was even interviewed by Gloria Steinem for a Ms. cover story during her Rhoda days!

Were the actors jealous of all the attention the actresses got? They seemed like wonderful friends in the end.

JKA: They were, a little bit. They all mentioned it, in fact, but mostly in a good-natured way. They loved the women, but they felt like they were getting more attention, particularly from Jay Sandrich, the director, which is what really got to them. I told Jay that, and he said he never even realized it, but even now, his answer was a playful, “Tough luck.” Honestly, I was struck by how much the entire cast seemed to still love each other.

Is it true that Lou Grant became a feminist himself?

JKA: He did! He’s quite cantankerous and hard to pin down on this stuff, so even when I tried to ask him about it now, he was a little squirmy. But the fact is that feminism is among the many political causes Ed Asner has championed. He was involved with NOW and gave a radio address for them about men in feminism. He also made sure there were women working on Lou Grant and getting paid fairly.

Who are some feminist characters on TV today?

JKA: The feminist-or-not question is always such a hot one these days, but I adore The Mindy Project, which addresses issues like body image and women’s professional success without being too “issuey” about it. Same goes for Girls, where Lena Dunham’s constant nakedness alone is a huge statement.

Holly Rosen Fink is a writer and marketer living in Larchmont, NY. You can follow her on Twitter @hollychronicles.

3 thoughts on “‘Mary and Lou and Rhoda and Ted’: Examining Feminism in ‘The Mary Tyler Moore Show’”

Comments are closed.