This guest post by Chantell Monique appears as part of our theme week on Women and Work/Labor Issues.

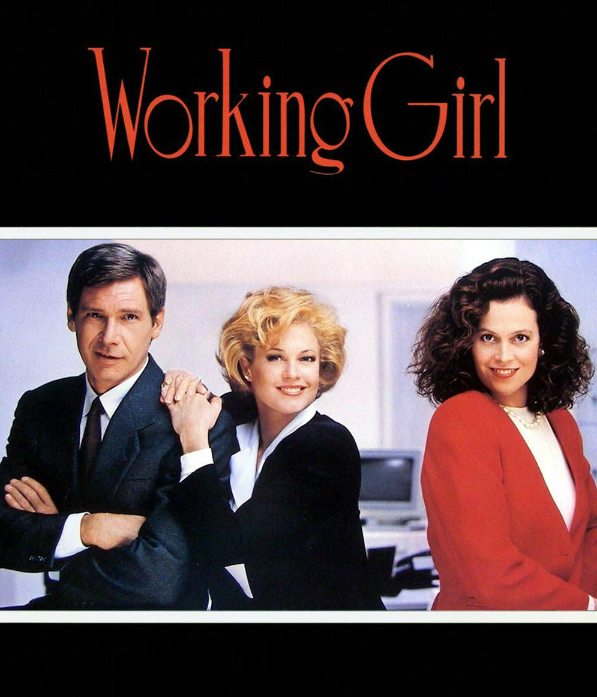

Mike Nichols’ Working Girl (1988) is centered on Tess McGill, played by Melanie Griffith, who is a Staten Island girl looking to make her way up the Manhattan corporate ladder. Although she has big hair, flashy make-up and gaudy jewelry, she’s soft-spoken, ambitious and smart. She may take the ferry into the city but she has dreams of being more than what people give her credit for. She’s a secretary who earned her night school degree with honors and feels she can “do a job” beyond fetching people coffee. More than anything, Tess is looking for her big break.

Enter her new boss, Katharine Parker, played by Sigourney Weaver. Katharine is everything Tess wants to be — she’s well-spoken, classy and successful. She looks like money and speaks with confidence and assurance. Although slightly intimidated by Katharine, Tess ultimately sees this pairing as her opportunity to finally get her career on track. Her hopes are strengthened more when Katharine tells her that their relationship is a “two way street” and empowers Tess to take control of her career.

Motivated by her good fortune, Tess shares one of her ideas with Katharine; the idea is fresh, and intuitive. Katharine tells her that she’ll look over her notes to see if the idea has potential. This is the opportunity Tess has been waiting for. She gushes to her boyfriend, played by Alec Baldwin, that Katharine takes her seriously and that she doesn’t have to endure the skirt chasing that comes with having a male boss. Working Girl gives us hope that Tess will finally get a chance to prove herself in the cutthroat corporate world. In addition, her boss is a woman—this means, she is educated, ambitious and from what we can tell, willing to help a fellow woman find success in a man’s world. This is a start to positive representation of women in the workplace—while from two different worlds, both are educated and determined to work hard to get what they want.

A freak skiing accident leaves Katharine in the hospital and unable to come into work. She asks Tess to take care her personal business, sending her to her home to handle a number of responsibilities. While perusing Katharine’s fancy living situation, Tess discovers a recorded memo from Katharine that explicitly states she seeks to pursue Tess’s idea without her, ultimately passing it off as her own. Heartbroken at her betrayal, Tess goes home early only to find her boyfriend in bed with another woman. With nowhere to go, Tess flees to Katharine’s home and after some soul searching, decides to exact her revenge.

This is where the movie shifts its direction in terms of female representation; what could be an opportunity to illustrate a harmonious relationship between two women in the workplace, instead does the opposite. Because Katharine steals Tess’s idea, we automatically pull for Tess, the lower-class underdog; consequently, we are forced to view Katharine, the upper-class princess, as the demonized, selfish boss, determined to achieve success no matter what. Hurt, yet motivated to take control of her career, Tess is now forced to lie in order to have her voice heard. This causes her to be pitted against a boss who has clearly abused her power. Even though Working Girl seems like a harmless, romantic drama, its female representation is firmly rooted in classism and sexism.

Tess finds herself in a difficult situation — she wants to move up the corporate ladder but no one takes her seriously because she’s a secretary. After discovering Katharine’s plan to hijack her idea, Tess sets up an appointment with Jack Trainer, played by Harrison Ford; she needs Jack’s help with making her idea a reality. With Katharine out of town, Tess has an opportunity to make a name for herself but before this can happen, she must refine her image. Insert the Hollywood makeover; Tess and her best friend Cyn, played by Joan Cusack, sit in Katharine’s bathroom—Tess with a beauty magazine and Cyn with a pair of scissors. “You sure you wanna do this?” Cyn asks, holding a piece of Tess’ hair. “You wanna be taken seriously, you need serious hair,” she replies.

Audiences are used to seeing makeover scenes where the ugly duckling emerges as a swan but this particular scene holds more meaning. Tess is the lower-class underdog; she has a heavy accent and her hair is teased to the ceiling. Instead of embracing her roots, she’s forced to leave her identity behind for corporate acceptance. It makes sense that she does this; unfortunately, by wearing Katharine’s clothes, cutting her hair and altering her dialect, the film manages to comment on which class has more power. If she needs serious hair to be taken seriously, then what kind of hair does she have before the makeover? As her evolution progresses it’s clear she’s trying to emulate Katharine who represents the upper-class princess, and ultimate model of success. In a classist society, this is an example of the upper-class being taken more seriously, having more power, and garnering the most respect.

Tess’s plan to thwart Katharine demonstrates the notion that women don’t belong in management. Women in power are seen as ruthless, am-bitch-ous and emotional. It’s this characterization that affects most women in power, pigeonholing them and undermining their success. This stereotype is evident in Working Girl; Katharine is a woman who in the beginning of the film is portrayed as focused, strong and willing to assist a female co-worker with her career. Unfortunately, as her character develops, it’s discovered that she’s not as honest as she seems. Because Katharine steals her subordinate’s idea, we now have to question her career veracity. Has she stolen other co-workers’ ideas in order to further her career? Tess went to Katharine because she was her boss; she respected her opinion and ultimately her position of power. By stealing Tess’s idea, Katharine abuses this power; her actions reinforce the stereotype that women are unable to handle management positions.

While the film relies on sexist tropes in order to create an antagonist for Tess, one has to wonder, what if Katharine was a man? Would a man have even respected Tess enough to listen to her? This creates a difficult position for Working Girl; one can argue that a man would not have listened to Tess; therefore, there wouldn’t be a storyline worth pursuing. They had to make Katharine a woman but by doing so, they portrayed her as conniving, devious and incapable, thus harming the female image.

Tess’s plan is under way; no one suspects she’s a secretary posing as management. Jack’s on board and everything is going well, including the fact that there is a connection between the two. But like most movies, all good things must come to an end. With the deal almost solidified and Jack and Tess clearly in love, she’s one step away from proving her worth. Not to be foiled, Katharine shows up at the meeting and blows Tess’s cover. In a corporate “cat fight” Katharine belittles Tess, makes her out to be crazy and steals her place at the meeting table. All is not lost for Tess, however. Days after the meeting, she runs into Jack, Katharine, and the group of men involved in the deal she put together. With Jack’s help, she’s able to prove to the CEO that it was her idea all along, telling him, “You can bend the rules plenty once you get to the top, but not while you’re trying to get there. And if you’re someone like me, you can’t get there without bending the rules.” Katharine makes one last desperate attempt to prove the idea was hers but everything crumbles around her.

The lower-class underdog manages to beat the woman who has everything. What’s interesting to note is that both women had to lie/cheat in order to achieve their goals. Katharine tried to cheat by stealing Tess’s idea and Tess had to “bend the rules” in order to have her voice heard. While this seems innocent, the film argues that women aren’t capable enough to get ahead on their own—that ultimately they must rely on lying or cheating in order to climb the corporate ladder and find success.

Working Girl is one of my favorite romantic dramas; unfortunately, it took a couple viewings in order to question its female representation in the workplace. Even though these images seem harmless, upon further investigation, they aren’t. Being able to recognize and question these images encourages viewers to challenge their line of thinking and perhaps even write alternative perspectives that can empower and strengthen the female image.

Chantell Monique is a Creative Writing instructor and screenwriter, living in Los Angeles. She holds a MA in English from Indiana University, South Bend. She’s a Black Girl Nerd who’s addicted to Harry Potter, Netflix and anything pertaining to social justice, and female representation in film and television. Twitter: @31pottergirl

4 thoughts on “The Corporate Catfight in ‘Working Girl’”

Comments are closed.