|

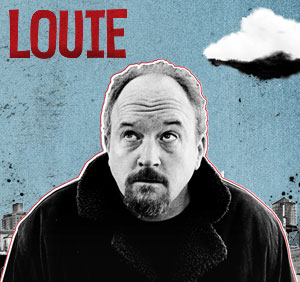

| Louis C.K.’s Louie |

“I remember thinking in fifth grade, ‘I have to get inside that box and make this shit better’… It made me mad that the shows were so bad. People have a right to relax and watch theater about themselves that makes them reflect and feel and have a good time doing it.” – Louis C.K.

The subversive feminism of a show is most striking when it is underneath, not necessarily a part of, the writing. From season 1 of FX’s critically acclaimed Louie, it has been clear that Louis C.K. isn’t trying to make some grand commentary on gender or social norms. He’s simply weaving stories out of life.

Louie–starring C.K. as Louie–is one of those shows that doesn’t leave a feminist audience balking at stereotypes or scrambling to celebrate its female empowerment (although C.K. is, in general, a feminist darling). In fact, its power lies in its ability to allow us to not think too much about gender; instead, we are focused on the stories and the sheer humanity of the characters.

Louie is a single father co-parenting two daughters in New York City and working as a comedian. The obviously semi-autobiographical sitcom is wrapping up its third season next week. A TV auteur, C.K. produces, writes, directs, edits, and stars in each episode. He has been nominated for three Emmy awards for the series (for acting, directing, and writing).

Early on, audiences felt there was something different about Louie. The best way to describe the ebb and flow of comedy and dramatic genius would be intensely human. Everyone is flawed (not just Louie, and not just his love interests and friends), and his relationship with his on-screen daughters is particularly moving in its stark honesty. We worry, panic, yearn, laugh, and cry along with our protagonist.

Parenting–a subject most often reserved for the action and commentary of mothers–is central to C.K.’s stand-up and to Louie. In the show, Louie is consistently shown as a capable father who loves and is loved by his daughters. He’s no heroic single father, but we see him as a parent, nothing less. On the subject of gender roles in parenting, C.K. has said, “Roles have all changed. There’s a lot of fathers who take care of their kids, there’s a lot of mothers who have careers. But in culture, those roles are still the same. When I take my kids out for dinner or lunch, people smile at us. A waitress said to my kids the other day, ‘Isn’t that nice that you’re getting to have a little lunch with your daddy?’ And I was insulted by it, because I’m like, I’m f**king taking them to lunch, and then I’m taking them home, and then I’m feeding them and doing their homework with them and putting them to bed. She’s like, Oh, this is special time with daddy. Well, no, this is boring time with daddy, the same as everything.” This philosophy is clear in Louie.

|

| Louie eats dinner with his two on-screen daughters. |

C.K.’s stand-up acts frame the plot(s) of each episode, which are usually independent to what has happened in previous episodes. This season alone, Louie has dealt with being sexually assaulted on a date (although some bloggers problematically downplayed the assault in semi-celebration of the challenged double standard), wrestling with a friendly attachment to a young handsome man on a trip to Miami, and experiencing awkward encounters with women as flawed as he is. He is frequently depicted as having the more stereotypically feminine role in relationships (emotional, needy, and looking for serious companionship). Previous seasons have featured him having sex with (and being inspired by) Joan Rivers, dealing with childhood issues surrounding religion and sexual awakening, and being an adequate son and brother. His daughters are continually portrayed as empowered and fully realized (including one episode in season 2 in which his youngest daughter helps scare off some teenage thugs on Halloween). As the girls grow up, their character traits become more pronounced and realistic.

|

| Parker Posey plays one of Louie’s love interests in season 3. |

Season 2’s critically acclaimed “Duckling” was an hour-long episode that followed Louie on a fictional USO tour to the Middle East. According to C.K., it was an accurate depiction of his real experiences on a USO tour to Afghanistan, and the idea for the episode came from his daughter, who was four at the time.

And for his show in general, C.K. says, “I just like listening. I try to take people who are way far away from what I think or understand and put a representative of them on my show.”

Indeed, one of the aspects of C.K. as a comedian, producer/director/writer/actor, and person that makes him who he is and Louie what it has been is that he listens. He listened to a four-year-old little girl and created a television show that is up for an Emmy. It’s also clear that he spent his original trip doing a great deal of listening to his fellow USO performers and the soldiers he met. That is what leads to great storytelling.

|

| C.K. used his own experiences and inspiration from his daughter to create “Duckling” in season 2. |

Outside of the television show, C.K. has also made it clear that listening is key to everything he does. After Daniel Tosh’s rape joke went viral earlier this summer, C.K. was brought into the spotlight after tweeting a complimentary tweet to Tosh (which he said he sent not knowing about the rape joke or the backlash). In an interview with Jon Stewart, C.K. addressed the fact that he listened to the bloggers–feminists, comedians, feminist-comedians–and altered his thoughts about the situation. He said, “I think you should listen when you read – If somebody has an opposite feeling from me, I wanna hear it so I can add to mine. I don’t wanna obliterate theirs with mine; that’s how I feel.” He went on to say that in being enlightened to the true ramifications of rape culture: “Now that’s part of me that wasn’t there before.”

In an interview with NPR last winter, C.K. was asked about his thoughts on those who identify as “right-wing” (after a discussion about Christians often stumbling across his stand-up after seeing a mild clip and asking him to “clean up” his comedy): “There’s been a lot of simple vilification of right-wing people. It’s really easy to say, ‘Well, you’re Christian, you’re anti-this and that, and I hate you.’ But to me, it’s more interesting to say, ‘What is this person like and how do they really think?’ Do I have any common ground with people like that who find me really, really offensive? Do I have common ground with them? It’s worth exploring.” C.K. clearly explores every piece of life he encounters, and that seeking, that analysis, makes all of the difference.

It’s no secret that listening to others’ stories leads to better storytelling (listening well pretty much leads to better everything). However, it’s rare that we witness that kind of storytelling on half-hour TV sitcoms. On the surface, a show produced, written, directed, and edited by one man (who also stars as the protagonist and is a comedian) doesn’t sound like it would be the panacea for three-dimensional storytelling. But as C.K. continually shows his audiences, episode after episode, listening to others and thinking about life critically has led him to accurately tell stories in a fully human way.

In an interview with the New York Times last summer, C.K. said, “An uphill battle is just more interesting to me.” Choosing to not rely on tropes and recycled story lines and stock characters is an uphill battle, but as Louie demonstrates, what’s on top of that hill is well worth the climb.

—

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.

Leigh Kolb is a composition, literature and journalism instructor at a community college in rural Missouri.

1 thought on “Listening and the Art of Good Storytelling in Louis C.K.’s ‘Louie’”

Comments are closed.