This is a guest review by Myrna Waldron.

|

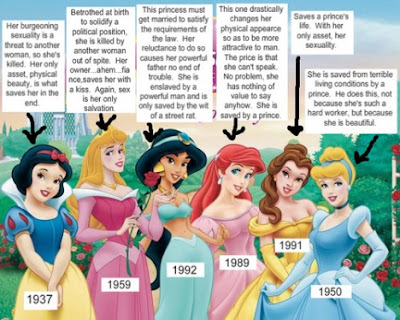

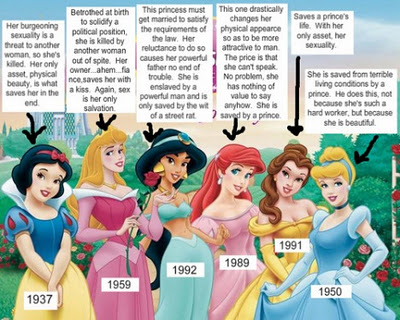

| “The sarcasm is practically melting off the screen!” |

But first, a few caveats. For the sake of my sanity, I will only be examining the original films that the characters first appeared in. No sequels, no supplemental film merchandising, no consideration of the Disney Princess merchandising line. Second, there is a lot of truth in the feminist criticisms targeted at the Disney Princesses. I credit most of these truths, however, to the contextual historical origins of the stories. The Grimm Brothers, Charles Perrault and Hans Christian Anderson predate modern feminism, as do the films made before the 1960s. Lastly, I will be concentrating on the 6 most common targets: Snow White, Cinderella, Aurora, Ariel, Belle and Jasmine. With all that clarified, let’s begin.

|

| “I wish I could get animals to help me do my chores.” |

Her song, “I’m Wishing”, reflects her emotional depth of character. It is not specifically a handsome boyfriend she longs for, she is longing for someone to love. That’s quite understandable considering she has lost everyone who loved her. “I’m Wishing” is a prayer for affection; “I’m hoping and I’m dreaming of the nice things he’ll say.” Her subsequent infatuation with the prince who meets her is another aspect of her personality. Since she is barely out of childhood, she still has a childlike trust and strong affection for anyone who treats her with kindness; we see this again later in her relationship with the Dwarfs, and her unfortunate trust in the disguised Queen.

What, then, of her famous domestic talents? Note that once she’s left the castle, she doesn’t do chores because she is expected to or forced to do them. When she stumbles upon the dwarfs’ cottage, she wonders if the messiness is because the inhabitants are orphaned children like herself. She sees herself in this situation; a motherless child forced to fend for herself. Her inherent sweetness and kindness shines through here. She volunteers to clean up the cottage because she does not want to deny anyone else that which she has been denied. This, I think, is a good feminist message. Women have been, and are, often denied rights and marginalized, but it is our conviction that someday this will end, and that if we can prevent it, or do anything else to help someone in a similar situation, we will gladly do so. And, like Snow White, when confronted with a difficult job, we will “Whistle While You Work” to give us strength to get through it.

|

| “So pure-hearted she can touch bubbles without bursting them.” |

I take further issue with the dismissal of Cinderella’s character as weak. Right at the start of the film, she displays a strong will, and a sharp wit. Her sarcastic ranting at the castle’s bells remains my favourite scene in the movie. She also has a strong rebellious streak; I highly doubt her stepfamily would have approved of her releasing the mice from the traps and her giving them little hats and shirts. This strong will and sense of rebellion comes to a point when Cinderella hears that every eligible maiden is to attend a ball held for the returning Prince. Her assertion that she is able to attend the ball as well is an assertion of her rights as a woman. Despite her marginalization and abuse from her family, she is, in this invitation, considered an equal. When her stepfamily tries to ensure she will not have time to make a dress, Cinderella steels herself not to be too disappointed about missing out on the ball, showing further strength of character. It is only when her stepsisters destroy her dress (in a scene disturbingly reminiscent of sexual assault) that she finally falls into despair; it is one abuse too many. I cannot fault her for her reaction at this point, as not only has she endured horrific emotional and physical abuse, she has yet again been denied one of the few things she has asked for. The ball, for Cinderella, represents her marginalized rights. At the ball, there is no class distinction, she has a chance to have fun for once, and she has a chance to meet other people (not just the prince). Her stepfamily can thus be interpreted as a representation of people who deny rights to women, and Cinderella can thus stand in for the oppressed women who fight against misogyny.

|

| “Aurora’s side of the wedding chapel was entirely comprised of animals.” |

Aurora has thus grown up only displaying the traits that the fairies’ magicked into her, and they have never allowed her to develop into anything other than their ideal. The fairies idealized Aurora so much that they never think to consider that she has a mind and a will of her own, and assume she would be overjoyed that they kept vital secrets from her for her entire life. In many ways, though it was with the best of intentions, the fairies/aunts have done Aurora a great disservice. Their loyalty and promise to the king seems to supersede their loyalty to someone they have raised like a daughter. Though Maleficent must magically hypnotize Aurora into touching the spindle, I believe it is the fairies’ insistence on obedience above all that partly led to Aurora’s downfall. In Aurora’s case, my feminist defense of her character will be one of empathy for her.

|

| “Disney’s ode to teenage angst.” |

Lastly, I wish to shortly refute the criticisms about the climax of the film. It is true that Ariel was incapacitated by Ursula’s magic, and that it was Eric who ultimately killed Ursula. However, only moments earlier, Ariel physically fought against Ursula, and even forced Ursula into accidentally destroying her pet eels, so she is obviously not weak and submissive here. I also think of the incapacitation as a dark echo of a sentiment Ariel expressed earlier in the “Part of Your World Song”; “Sick of swimming, ready to stand.” As a mermaid, she feels and has been exploited into uselessness, as a human, she’s ready not only to physically stand, but to metaphorically stand up for herself.

|

| “I sing to my books all the time, don’t you?” |

Feminist messages in the film are also easily indicated by the differences between Belle’s two suitors, the Beast and Gaston. At first, there is not much difference between the men; neither initially takes Belle’s wishes and desires into account when courting her. Note that Belle is undaunted by the lack of respect shown by the men; she ignores Gaston’s dismissal of her interests and responds to his flirtations with sarcasm, and she stands up to the Beast when he has his temper tantrums. Interestingly, both actions demonstrate different kinds of courage: to rebuff the advances and “advice” of a leader of the village shows further confidence and courage in her nonconformity, and to stand up to and argue with a physical embodiment of fear is symbolically feminist of our efforts to stand up to those that would use fear to subdue us.

Later on, Gaston openly proposes to Belle, and affirms his characterization as a male chauvinist. His plans for his marriage to Belle involve forcing her into subservience; he fantasizes about her massaging his feet and bearing him 6 or 7 “strapping” boys (he evidently doesn’t value female children). Once again, he shows no concern for Belle’s wishes and assumes that this life is what all women dream of. Once Beast’s personality starts to change, he differentiates himself from Gaston. He no longer tries to force her affections (such as the demand that she join him for dinner), and shows that he values her intellectualism and cares about her interests when he gifts her the library. In the third act, there is almost a role reversal in the evolution of Gaston and Beast’s characters. Gaston tries to “trap” Belle into marriage through blackmail, and the Beast officially “frees” Belle (though at this point she is arguably staying in the castle willingly) out of love for her, knowing that she may never return. The suitors’ very different approaches to relationships thus serve as excellent examples for the types of relationships that feminists seek to end/embrace: We reject relationships solely based on the wants and desires of the man with no consideration of the woman’s feelings, and seek relationships of mutual respect and understanding, with careful consideration of the interests, wants and desires of both partners.

|

| “I like making you feel uncomfortable.” |

Jasmine is characterized as a woman with an intelligence, courage and wit that surprises the men around her (which is perhaps a subtle jab at Middle Eastern oppression of women). Her escape from the palace shows a feminist emotional fortitude; she will put her happiness first. She catches on to Aladdin’s schemes very quickly, showing that she is just as clever about getting out of bad situations as he is. One particularly controversial scene (the one I have pictured) involves her quick-thinking abilities. In order to distract Jafar, she exploits his attraction to her by pretending that she has magically fallen in love with him. It is partly a scene about using her sexuality as a weapon, but I also believe that her actions are equally as much about utilizing her intelligence and adaptability to any situation.

|

| “How can you tell this is fanart? The Characters show an actual personality.” |

—–

Thank you SO MUCH for this. I’ve been arguing those exact points for Ariel for years now; it feels nice to have them validated. And the other characters you mentioned gave me a lot to think about.

And the other characters you mentioned gave me a lot to think about.

This was an amazing analysis of the characters! I loved all your points and everything was so well stated. Its so incredible to read a feminist defense for the disney princesses

As a Disney Princess kind of lady I am so glad you’ve written this post. Because yes, there are a lot of problems with the princesses. But they were so much a part of my childhood (and let’s be honest, my adulthood as well) and I love them so much that it’s nice to see them defended as well. As a brunette with her nose perpetually buried in a book Belle especially was important to me and I probably cried for an hour in my Intro to Women’s Studies class when we were presented with the Stockholm Syndrome reading of her character. Anyway, I dig your analysis and it makes me feel a little bit more comfortable with myself and my love for the princesses. Well thought out and well written 😀

Excellent points all. I think the reason some feminists are irritated out of proportion to their sins at the Disney Princess films is their monolithic quality – as you point out, within that narrative framework there’s a lot of room for decency and specificity, but it is still pretty much the only narrative framework sold to girls. I think most people would be easier on the Disney Princesses if there were also Disney stories about females that weren’t pretty royals, the way they’ve always been willing to do that with men (Milo Thatch, Pinocchio, Robin Hood).

I agree with some of your points and disagree with others, but I’m glad to see another feminist put out an alternate view on our Disney ladies.

My opinion? Well it really depends on the film. As you point out, the pre-60s Disney princesses can’t really be expected to conform to post-women’s lib ideals–pointing out what’s wrong with those portrayals has always seemed kind of tiresome and pointless to me. That said, I agree with your analysis of Cinderella. I never saw her as a pushover, just a woman who was doing her best to cope with a crappy situation and who could show real strong-mindedness at key moments. Snow White’s character is pretty flat to me. I think the thing to remember there is that it was an experimental film at the time, being the first feature length animated film, and that none of the characters are particularly well-developed. I think they were still trying to figure out how to sustain an animated narrative for that long.

Aurora–well, as you say, it’s not really about her. I loved “Sleeping Beauty” as a child, but it was all about watching the fairies produce pretty dresses and cakes in puffs of glitter with their magic wands (which still makes me inordinately happy…) to me. I didn’t really give Aurora much thought and I don’t think most kids watching it do.

Belle–Right on with this one! I am very protective of my girl! She was my hero when I was little, since I was a bookworm and a daydreamer who was thought odd by my peers. And I agree with your commentary on her relationships with Gaston and the Beast 100%. I’ve always thought the Stockholm Syndrome interpretation was really silly too. I wish all young women handled men with the Belle’s self-possessed assuredness

As for Jasmine and Ariel, I have mixed feelings. I’m completely with you that the most important scene in the Little Mermaid is “Part of your world.” It’s such a beautiful metaphor, not just of the outsider who longs to find a place, but of adolescence, that period in life when you begin to realize how small your world is and yearn for adventure and experience. That last shot of her from above, staring longingly up at what’s beyond almost brings tears to my eyes. My main issue is that, once Eric comes into the story, the romance kind of highjacks the whole thing and then it DOES become all about getting her man. Although I agree with you about Ursula’s rant–anyone who takes that at face value needs to take an English class.

My main issue with Jasmine is that they felt the need to dress her like “Harem Barbie” or something, and give her the affect of a petulant teenager. Belle seems much more like a grownup and she was beautiful without being a sex object. Mostly, I think there’s more race issues with Aladdin then gender issues. And, hoo boy, is that film ever racist!

Also, (I know, I’ve already written a book) somewhat aside from purely feminist issues but still relevant, I think Beauty and the Beast provides some really interesting commentary on mob mentality and the demonization of “Others.” In the beginning of the film, Belle’s neighbors in her “provincial town” are harmless, friendly folk who consider her and her father nothing more than “rather odd” but never threatening, and their worship of Gaston seems stupid but benign and is played for laughs. But then, after their fear of the Beast is exploited by the powerful, manipulative Gaston, his cult status becomes a sinister thing and they are transformed into a hysterical torch mob, psyched up to kill and all too happy to turn on Belle and Maurice, who were always just a bit too different anyway. In the end, I think Belle finds her soulmate in the Beast, not just because her respects her mind but because she relates to him–they are both outsiders in a world that fears what is different.

Howard Ashman, the lyricist for the film who wrote “Little Town” and “Kill the Beast” was not only a Jew of the post-Holocaust generation but a gay man with AIDS. I really think that shows.

I enjoy Disney films, but I think it would be better to say that there are some good things and bad things about them. It’s not one or the other.

I just wanted to address this:

“Jasmine is characterized as a woman with an intelligence, courage and wit that surprises the men around her (which is perhaps a subtle jab at Middle Eastern oppression of women)”

The fact that she surprised the men around her is pretty indicative of Disney’s racism and orientalism. It’s a further, unrealistic, depiction of Arab men as grunting savages that think poorly of women.

“I will have to step on a few minefields here by pointing out that the sultan’s allowing Jasmine to choose her own husband is already astoundingly feminist for medieval Arabia (we unfortunately don’t see that kind of freedom often even today).”

Just to make a correction: Arabia didn’t have a Middle Age. That is a distinctly European time period. The “Arabian” (there’s no indication where Jasmine’s from) period that coincides with Europe’s medieval period is the “Islamic Golden Age,” characterized by many philosophical and scientific advances…and it might surprise you that Arab feminists have been around since then too.

The following two blogposts summarize the issue pretty well:

http://irresistable-revolution.blogspot.com/2011/09/jasmine-diaries-part-i-colonial.html

http://irresistable-revolution.blogspot.com/2011/09/jasmine-diaries-part-ii-exotic-is-not.html

Your post was enjoyable.

http://www.politiciansathogwarts.blogspot.com

This comment has been removed by the author.

Thanks for everyone’s kind and wonderful comments, especially Lydia & Sarah’s.

Lydia, your insight on the “other” in Disney films is fascinating, and I’d like to see a full exploration of it. When I think about it, quite a few Disney films are about social isolation, so there’s plenty to write about there.

Sarah, I’ll have to apologize for my blatant ignorance on Islamic and Middle Eastern culture and history – as you have pointed out, my basis of knowledge is very European/North American. One of the big problems with analyzing Aladdin (and by extension, Jasmine) is how loaded the racist issues in the film are. The kindest thing I can say about the intentions of the film (and it’s one of my favourite Disney movies) is that they thought exoticizing the era and its people was flattery instead of a blatant misrepresentation. I’ll be sure to read those blog entries!

At least I’m not the only one who is arguing about the Cinderella business that Ella (her birth name) had no where to go, if she HAD left the step-family. I’m glad someone else is also arguing that B&tB isn’t about Stockholm syndrome (I been aruging that for awhile)

Thank you for this argument! It’s heartening after reading the particularly dreadful review of Beauty and the Beast elsewhere on this site. I too find that cartoon posted at the top of the article (and that other review) obnoxious for fundamentally misrepresenting the stories… Yes Jasmine and Belle, for example, are only valued as a sexual object, which is exactly what they are fighting against throughout their movies. Not to mention that a similar lens will show that Disney doesn’t have a whole lot of positive things to say about men either (especially if you’re unattractive).

The sense I get with Aurora is that the viewer’s relationship with her is formed more by her personality than her character. You don’t learn too much about her (a friend of mine described her a plot device rather than a character), but you get a very strong sense of what sort of a person she is. I actually like her sass and sense of humour, and think she is a stronger personality than most of the others. Speaking of which…

Your defense of Cinderella is interesting and will force me to take another look at her. She is my least favourite of the princesses because I’ve always seen her as simpering and indecisive. I like the fairy tale in general for its Magnificat-like theme, but I’ve been ambivalent about the Disney version. Time to watch it again.

@Torchy: Disney has its share of heroines that are not princesses: Alice, Lilo, Jane, Lady, Mary Poppins (going outside of animation), Mulan…

@Cory Gross – I think you might be referring to my review of ‘Beauty and the Beast’ where I share my love/hate (or rather love and massive frustration and annoyance) relationship with the Disney film. Yes, Belle is awesome. No doubt about it. She’s intelligent, kind, strong-willed and outspoken. Love her, always have, always will. But that negate the sexist messages imbued in the film. And it doesn’t mean I can’t criticize those elements. We may disagree on our interpretations but how did I misrepresent the story?

@Myrna – This is long overdue but while I may not agree with everything you wrote, I absolutely adore this piece. Brilliant!

Hi Megan, thanks for the reply!

I think what struck me the most about your review was the underlying subtext that you wish it was a different story. It’s main fault is that it is Beauty and the Beast and not something else (you even made a point about the title). Many of your recommendations for what they could have done to make it more feminist (i.e.: Belle not being Belle, Belle not humanizing the Beast, the Beast not being male, Belle opening up a bookshoppe, etc.) would have made it not Beauty and the Beast. If one wants to say that this story fundamentally sucks and should be forgotten that is their perogative, but I think if we’re going to analyze a story we have to first respect what the story is.

After that, I think you were wrong about the Stockholm Syndrome for reasons outlined in this article. And I think your emphasis on her value centring on her physical attractiveness is rather contrary to the whole point of the movie (you called it ironic, but no, the contrasts of beauty and ugliness were exactly the point) and her own struggle as a character not to be valued simply for her looks. The point about the Beast not being a woman was a bit of a non-sequitur and I can’t help but contrast that against the cynical, cruel honesty of Hunchback of Notre Dame where the ugly guy didn’t get the girl and that’s okay because ugly people can be happy without companionship, right? (I know that’s veering into “nice guy” territory) I also think that the feminist critique begets a certain myopia about how men are represented in this film (i.e.: Belle is the only decent attempt at a human being in it… Apparently as a man I get a choice between being a bumbling old fool, a beefcake asshole or a slavering monster until I’m humanized by a woman).

I’m also trying to figure out your 12 of 51 number for female protagonists. I counted at least 22 that had either a sole or co-protagonist who was female (and 7 compilation features that don’t have protagonists at all).

I think there are things that one can be concerned about in it (I’m mostly skeeved out by the bestiality, if I were to take it literally… I don’t tell that to my girlfriend though, as Beauty and the Beast and Mary Poppins are her favourite Disney movies). I think overall your review misses the larger themes of the story and doesn’t show much respect for the fact that it is this story and not a different story. In the context of it being Beauty and the Beast I think they did a fine job crafting an intelligent, literate, self-assured, and self-sacrificial character. Belle is not just the princess: she is the hero.

Hi Cory! My pleasure…and thank YOU for your reply I truly appreciate it!

I truly appreciate it!

I never said the Beast shouldn’t have been male. I said that the message is that beauty is only skin deep…for men. That we should look past appearances in men. But women must still be beautiful. If the point was that beauty doesn’t matter, we wouldn’t have had literally every single person — male and female, from the servants to the people in the village — commenting on Belle’s exquisite beauty. Isn’t it what’s inside that counts?

As far as Stockholm Syndrome goes, I stand by what I wrote. As I commented on my original post: I know not everyone sees the film as possessing Stockholm Syndrome. But Stockholm Syndrome doesn’t mean Belle would change herself. It means that a prisoner becomes acutely sympathetic to their captor, going so far as defending them and their oppressive behavior. This is exactly what happened here.

I completely disagree that recommending changes to this or any film or TV show is disrespectful. I don’t like to criticize something without offering potential alternatives. And adaptations take liberties with plotlines all the time. Disney changed Beauty into the bibliophile Belle, definitely a change for the better!

I’m not saying Disney doesn’t have huge problems depicting masculinity like in ‘The Hunchback of Notre Dame’ (although I didn’t see it so I can’t comment on it) — they definitely do. But there’s a much greater variety of male characters than female characters depicted in the media. Which is why I spend more time analyzing and critiquing women’s roles in media.

The 51 films were all the theatrically released Disney films. So I went back and checked my math. I hadn’t originally counted ‘The Aristocats,’ ‘The Rescuers’ and ‘The Rescuers Down Under’ as Eva Gabor’s character in both films was a co-protagonist, at times feeling secondary to the male characters. And I missed the female-fronted ‘Home on the Range.’ So here’s the list of 16 films with female protagonists or co-protagonists:

Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, Cinderella, Alice in Wonderland, Lady and the Tramp, Sleeping Beauty, The Aristocats, The Rescuers, The Little Mermaid, The Rescuers Down Under, Beauty and the Beast, Pocahontas, Mulan, Lilo & Stitch, Home on the Range, The Princess and the Frog, and Tangled.

Even though Belle isn’t the one who goes on an emotional transformation or a journey of self-discovery (the Beast does), I wholeheartedly agree with you that Belle is the hero of the story. And that’s a huge step in the right direction. But that doesn’t mean there’s not massive amounts of patriarchy embedded in the film and that we don’t still have far to go.

P.S. Your girlfriend has great taste. Not only do I still love ‘Beauty and the Beast,’ I love, love, LOVE ‘Mary Poppins’…and I wrote a post all about it here at Bitch Flicks too

Thanks again for the reply!

I disagree with your point about “I said that the message is that beauty is only skin deep…for men.” There is just no way of knowing that, because that’s not the story (though it would have made for a Hell of a surprise ending!). On the contrary, one could interpret the ending as a cheat: Oh, he’s good looking anyways. Great. However, the whole movie has a tonne of interplay between ideas of inner and outer beauty that encourages more generous interpretations.

I don’t believe that the movie reinforces the idea that women must be beautiful because Belle’s struggle to be recognized as a person beyond just a babe is central to the story. The movie has pretty clear messaging that there is more to her than her appearance and she yearns to have that recognized… The view that only her looks matter is the position of the villain.

Regarding Stockholm Syndrome, the difference here is that Belle consistently stands up to him and it’s the Beast who changes. Her presence humanizes him, including the fact that she’s not cowed by him, and it’s his changes that she is responding to. I agree that their relationship is very definitely one of captor-captive at the beginning, but the whole plot revolves around the fact that she is the catalyst for his change.

I don’t think that changing a work is disrespectful in itself. What I was pointing to is the subtext of wishing that it was not Beauty and the Beast. Artistically, I think that the desire to whitewash the plots of stories – especially classic stories – to make them fit a certain innoffensive ideal is a disordered ambition (it’s part of what made The Princess and the Frog not all it could have been). It makes for bad art, bad drama, even bad social justice… I’d rather see new interpretations of Beauty and the Beast that explore different facets of the story than to just washout the story altogether because putting a woman in a place of subjugation to a man is patriarchal. Of course it is! That’s the story!!

(FYI, my favourite version of the story is Jean Cocteau’s film, which is accutely about homosexuality)

I agree with your observation that “there’s a much greater variety of male characters than female characters depicted in the media” and that it is a problem. However I don’t believe that the Bedchel Test is an absolute standard that all stories should be judged by. One of my favourite Disney films is 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea, which has no female characters (and practically no women at all). And that’s okay. It doesn’t have to. It’s under no obligations to. It would be awesome to see a gender inversion of the Victorian “Boy’s Own Adventure” story, but that’s not this particular story.

Anyways… My list of Disney films with female (co-)protagonists included all of yours as well as Tarzan, Hunchback of Notre Dame, Aladdin, 101 Dalmations, Atlantis and The Black Cauldron. The 7 without protagonists at all are Fantasia, Saludos Amigos, The Three Caballeros, Make Mine Music, Fun and Fancy Free, Melody Time, and Fantasia 2000.

Thanks again for the opportunity for discussion!

You did the best defense of Snow White that I had ever had the pleasure to read (I never though that what she does for the dwarves when she finds their cottage is because of her own experience as an orphan).

This was really well written and I’m happy because so many of the reviews on this site are so radically feminist and criticising that they’re unbearable.